Abdominal pain in horses represents one of the most critical veterinary emergencies that equine owners face today. Colic in horses is a broad term for abdominal pain, often from gastrointestinal issues like gas, impaction, or blockages, but can stem from other organs, with signs from mild (lethargy, pawing) to severe (violent rolling). It’s a common emergency requiring immediate veterinary attention, as causes range from manageable (dietary stress, dehydration) to life-threatening (surgical obstructions). Understanding this condition can mean the difference between life and death for your beloved horse. This comprehensive guide provides essential information about gastrointestinal distress in equines, helping you recognize warning signs and take immediate action.

Understanding Equine Colic: What Every Horse Owner Must Know

Equine abdominal pain encompasses a broad spectrum of gastrointestinal disorders that affect horses worldwide. Veterinarians define this condition as any form of belly discomfort, typically originating from digestive system complications such as intestinal gas buildup, feed impaction, or dangerous blockages in the digestive tract.

However, the pain doesn’t always stem from the gastrointestinal system alone. Other internal organs, including the kidneys, reproductive organs, and liver, can trigger similar distress signals. The condition manifests across a wide severity range, from mild discomfort characterized by subtle lethargy and occasional pawing, to severe episodes involving violent rolling behavior and life-threatening complications.

Emergency veterinary intervention becomes absolutely critical when horses display these symptoms. The underlying causes span from relatively manageable issues like dietary stress and inadequate water consumption to severe, life-threatening situations requiring immediate surgical intervention for intestinal obstructions or twisted bowel segments.

Common Causes of Abdominal Pain in Horses: Identifying Risk Factors

Dietary Factors Leading to Digestive Upset

Nutritional management plays a fundamental role in preventing digestive emergencies. Sudden feed changes disrupt the delicate microbial balance in the equine hindgut, causing fermentation problems and gas accumulation. Grain overload occurs when horses consume excessive concentrated feeds, leading to rapid carbohydrate fermentation and potentially fatal acidosis.

Poor-quality forage containing mold, dust, or inadequate fiber content fails to maintain proper gut motility. Horses evolved as continuous grazers, and their digestive systems require consistent, high-quality roughage to function optimally.

Dehydration and Water Intake Issues

Insufficient water consumption stands as a primary contributor to impaction episodes. When horses don’t drink adequate amounts of fresh water, the intestinal contents become dry and compact, forming solid masses that obstruct normal passage through the digestive tract.

Cold weather, unpalatable water sources, travel stress, and illness all reduce voluntary water intake. A 1,000-pound horse typically requires 5-10 gallons of water daily, with increased needs during hot weather or intense exercise.

Parasite Infestations and Internal Damage

Intestinal worms cause significant irritation to the gut lining and can create physical blockages when present in large numbers. Strongyles, roundworms, and tapeworms damage blood vessels, compromise intestinal wall integrity, and form masses that obstruct digestive flow.

Modern deworming protocols have reduced parasite-related cases, but inadequate parasite control programs still pose serious risks, particularly in young horses and those with compromised immune systems.

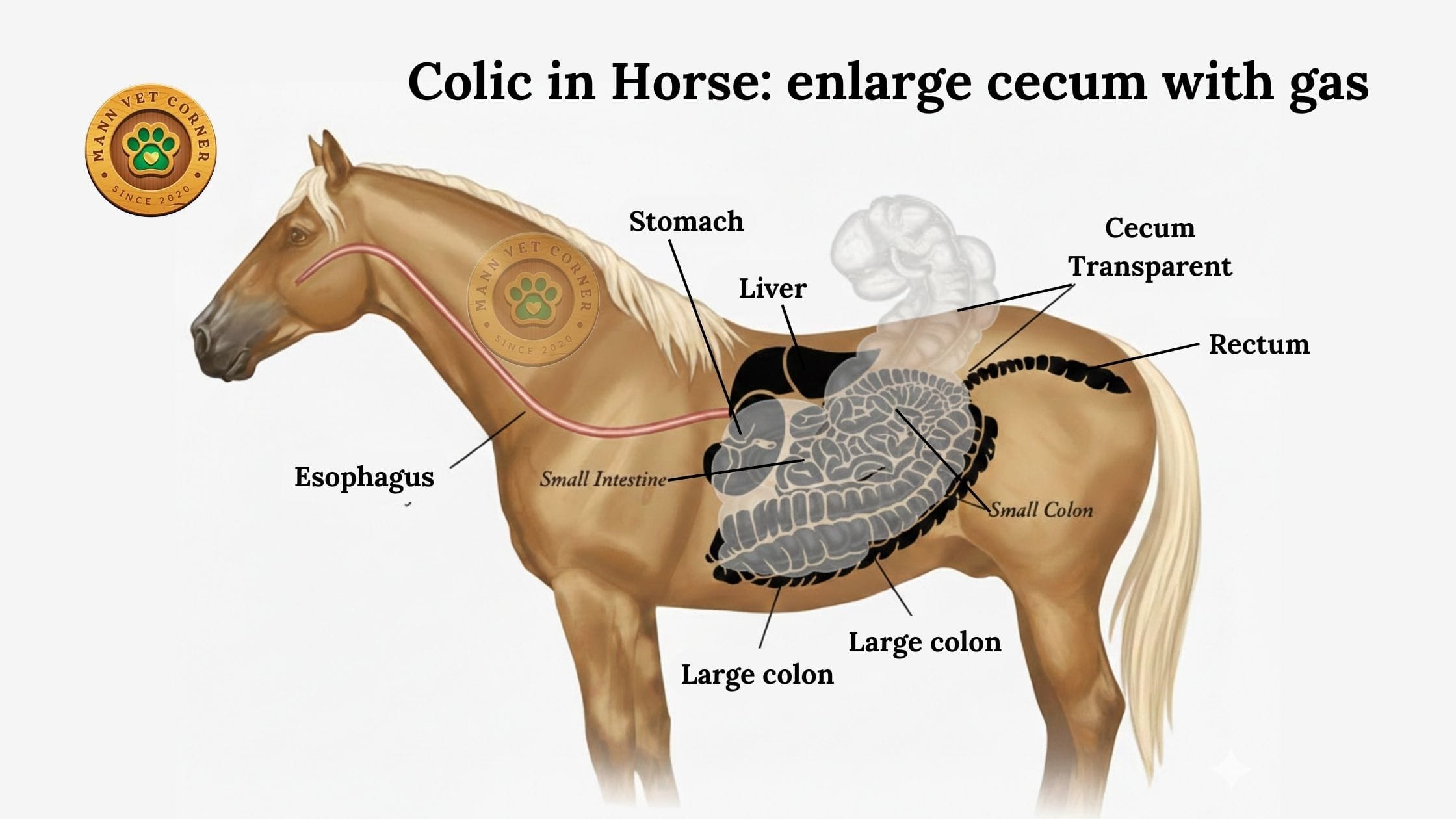

Gas Accumulation from Fermentation

Excess intestinal gas develops when fermentation processes accelerate beyond normal levels. Dietary factors, stress responses, and sudden changes in feeding routines trigger abnormal fermentation patterns in the cecum and large colon.

The equine digestive system cannot expel gas through belching, making horses particularly vulnerable to painful gas distension. This pressure builds within intestinal segments, causing significant discomfort and potentially compromising blood flow to affected areas.

Feed and Sand Impaction Blockages

Physical blockages form when feed material, sand particles, or foreign objects accumulate in the intestinal tract. Horses grazing on sandy soil inadvertently ingest sand particles that settle in the large colon, creating heavy, abrasive masses.

Feed impaction typically occurs at natural narrowing points in the digestive system, particularly at the pelvic flexure of the large colon. Coastal Bermuda hay, wheat straw bedding, and coarse, stemmy forages increase impaction risk.

Environmental Stress and Management Changes

Stress triggers numerous physiological changes that affect digestive function. Environmental modifications, travel demands, intensive training schedules, competition stress, and changes in stable companions all disrupt normal gut motility patterns.

Horses experiencing stress often reduce their feed and water intake, alter their movement patterns, and develop tension that translates into digestive dysfunction. The gut-brain connection in horses proves remarkably sensitive to environmental stressors.

Recognizing Clinical Signs: Symptoms of Horse Colic by Severity Level

Mild Symptoms Indicating Early Distress

Early recognition of subtle symptoms allows for prompt intervention before conditions escalate. Horses experiencing mild abdominal discomfort exhibit several characteristic behaviors that alert observant owners to developing problems.

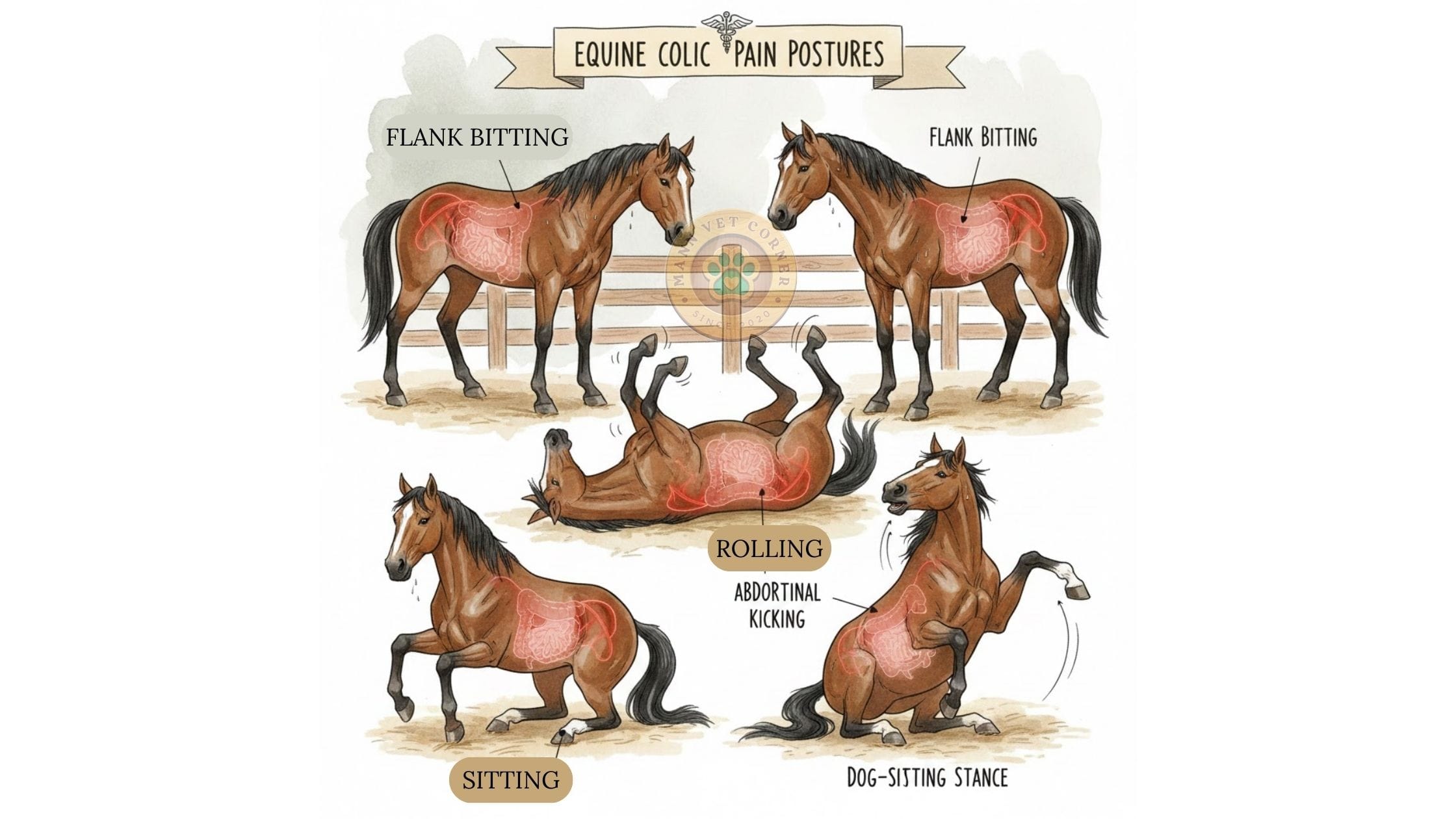

Pawing at the ground represents one of the earliest warning signs, as horses attempt to communicate their discomfort. Repeatedly looking back toward the flank area indicates localized pain awareness. General restlessness, shifting weight frequently, and inability to settle comfortably suggest underlying distress.

Loss of appetite or reduced interest in feed deviates from normal eating patterns. Excessive yawning, though sometimes overlooked, can signal nausea or abdominal tension. Slight sweating without apparent cause, particularly around the neck and flanks, indicates pain responses. Decreased manure production or changes in fecal consistency warrant immediate attention.

Severe Symptoms Requiring Emergency Response

Advanced stages demand immediate veterinary intervention to prevent catastrophic outcomes. Violent rolling behavior poses extreme danger, as horses may twist intestinal segments, creating surgical emergencies. Thrashing movements reflect intense, uncontrollable pain that overwhelms normal behavioral inhibitions.

Continuously lying down and rising repeatedly demonstrates the horse’s desperate attempt to find relief from severe discomfort. Aggressive kicking toward the abdomen shows the horse actively responding to localized pain. Profuse sweating covering large body areas indicates systemic stress responses and severe pain levels.

Marked depression, with the horse standing motionless with a glazed expression, suggests deteriorating condition and possible shock development. Clinical shock signs include pale or blue-tinged mucous membranes, dramatically elevated heart rate exceeding 60 beats per minute, rapid shallow breathing, and cold extremities.

Emergency Response Protocol: What Horse Owners Should Do Immediately

Step One: Contact Your Veterinarian Without Delay

Immediate veterinary communication represents the single most critical action when abdominal pain symptoms appear. Timely professional diagnosis and treatment intervention dramatically improve outcomes and can prevent life-threatening complications from developing.

Provide your veterinarian with detailed observations about symptom onset, duration, severity level, and any triggering events. This information helps the veterinarian prioritize the emergency and prepare appropriate equipment and medications.

Step Two: Careful Observation and Documentation

Note specific behavioral changes, their intensity, and frequency patterns. Document vital signs if you can safely obtain them, including heart rate, respiratory rate, and gum color. Record the last time the horse ate, drank, and passed manure.

This detailed information proves invaluable for veterinary assessment and helps track whether the condition improves, stabilizes, or deteriorates while awaiting professional arrival.

Step Three: Remove All Feed Sources

Immediately remove hay, grain, and any other feed materials from the horse’s environment. Continued eating can worsen impactions, increase gas production, and complicate potential surgical interventions requiring anesthesia.

Ensure water remains freely available unless your veterinarian specifically instructs otherwise. Maintaining hydration supports treatment efforts and prevents secondary complications.

Step Four: Consider Gentle Walking (With Important Limitations)

Light hand-walking may benefit horses showing mild symptoms by encouraging gut motility and preventing the horse from rolling. Walk the horse slowly for 10-15 minute periods with rest intervals.

However, stop walking immediately if the horse’s condition worsens, pain intensifies, or the horse makes repeated attempts to roll violently. Forced exercise during severe episodes causes unnecessary stress and may worsen intestinal displacement.

Step Five: Never Administer Medications Without Veterinary Guidance

Resist the temptation to give pain relievers, home remedies, or medications without professional consultation. Pain medications can mask symptoms that veterinarians need to assess for accurate diagnosis. Some medications interfere with subsequent treatments or create dangerous drug interactions.

Wait for veterinary guidance regarding all medication administration, including commonly used products you may have on hand.

Professional Veterinary Diagnosis: How Veterinarians Assess Equine Colic

Comprehensive Physical Examination Procedures

Veterinarians conduct systematic physical assessments to determine the condition’s nature, severity, and appropriate treatment approach. Vital sign evaluation includes measuring heart rate, respiratory rate, body temperature, and capillary refill time in the gums.

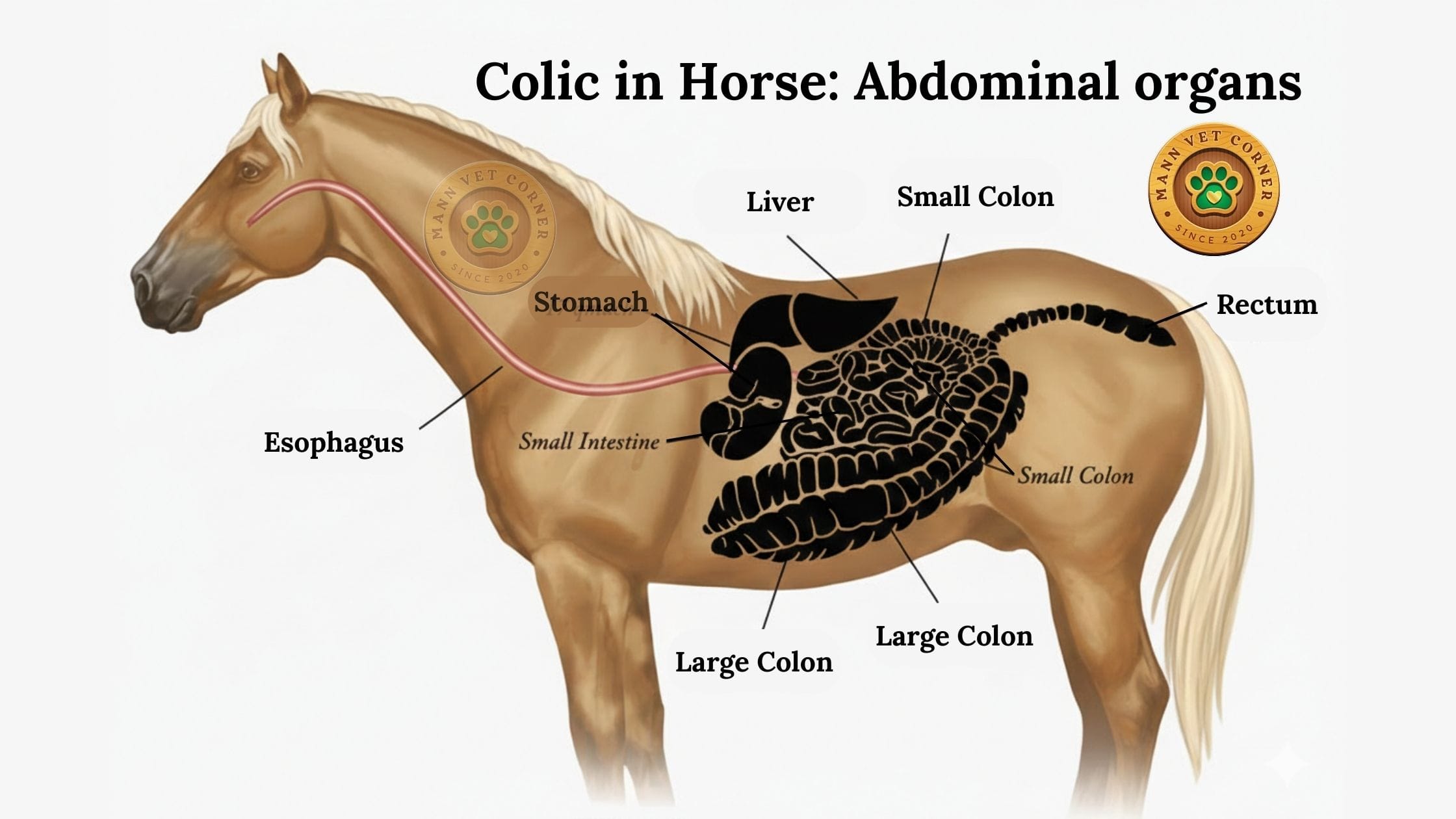

Auscultation of gut sounds in all four abdominal quadrants reveals important information about intestinal motility patterns. Absent sounds suggest ileus or complete obstruction, while hyperactive sounds may indicate spasmodic pain or early obstructive processes.

Mucous membrane evaluation assesses hydration status and circulatory function. Pale, dark red, or bluish gum coloration indicates compromised circulation and potential shock development.

Rectal Palpation Examination

Rectal examination allows veterinarians to physically assess portions of the intestinal tract, detecting impactions, displacements, gas distension, and abnormal positioning of intestinal segments. This diagnostic procedure provides critical information unavailable through external examination alone.

Experienced veterinarians can identify specific problems including large colon impactions, cecal distension, small intestinal distension, nephrosplenic entrapment, and reproductive organ abnormalities.

Nasogastric Intubation and Reflux Assessment

Passing a stomach tube through the nostril into the stomach serves dual diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The procedure allows veterinarians to detect gastric reflux, which indicates small intestinal obstruction or ileus.

Large volumes of reflux require immediate decompression to prevent stomach rupture, a rapidly fatal complication. The tube also enables administration of mineral oil, water, or medications directly into the stomach.

Advanced Diagnostic Imaging

Severe cases may require abdominal ultrasound examination to visualize intestinal wall thickness, detect fluid accumulation, assess motility in real-time, and identify structural abnormalities. Larger equine hospitals offer additional imaging modalities including radiography for foals and small horses, and even CT or MRI scanning in specialized facilities.

Blood work analysis reveals important systemic information about hydration status, electrolyte balance, infection presence, and organ function that guides treatment decisions.

Treatment Approaches: From Medical Management to Surgical Intervention

Medical Management for Non-Surgical Cases

Many episodes resolve successfully with conservative medical treatment when diagnosed early and managed appropriately. Pain relief through non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs helps reduce discomfort, decrease intestinal inflammation, and improve gut motility.

Flunixin meglumine represents the most commonly used pain medication, providing effective analgesia and anti-inflammatory effects. In some cases, stronger analgesics including butorphanol or detomidine become necessary for adequate pain control.

Mineral Oil Administration and Laxative Therapy

Veterinarians administer mineral oil through the nasogastric tube to lubricate intestinal contents and soften impacted material. The oil doesn’t absorb systemically, instead coating feed material and facilitating passage through the digestive tract.

Additional laxatives, stool softeners, or psyllium products may supplement treatment depending on the specific diagnosis and clinical presentation.

Intravenous Fluid Therapy

Dehydrated horses require aggressive fluid replacement to restore normal hydration, improve circulation, support kidney function, and soften impacted intestinal contents. Large volumes of balanced electrolyte solutions administered through intravenous catheters correct fluid deficits and maintain ongoing hydration needs.

Fluid therapy continues until the horse shows clinical improvement, begins drinking adequately, and demonstrates normal gut function restoration.

Hospitalization for Intensive Monitoring

Moderate to severe cases benefit from hospital admission allowing continuous professional monitoring, repeated examinations to track progress, intensive nursing care, and immediate intervention if the condition deteriorates.

Hospital settings provide controlled environments optimizing recovery while minimizing stress and complications.

Emergency Surgical Intervention

Life-threatening conditions including intestinal torsion, strangulating obstructions, severe displacements, or cases failing to respond to medical management require emergency abdominal surgery. Surgical exploration allows veterinarians to directly visualize abdominal contents, correct displacements or torsions, remove non-viable intestinal segments, and address problems inaccessible to medical treatment.

Survival rates for surgical cases depend heavily on timing of intervention, with early surgery dramatically improving outcomes compared to delayed procedures after intestinal compromise has progressed.

Prevention Strategies: Reducing Risk Through Proactive Management

Maintaining Consistent Dietary Programs

Feed horses on regular schedules with consistent high-quality forage forming the diet foundation. Make any feed changes gradually over 7-10 days, allowing gut microbiome adaptation. Avoid sudden switches in hay type, grain brands, or feeding times.

Provide adequate fiber through grass hay, limiting rich alfalfa for most horses. Measure grain portions accurately rather than feeding by volume, and consider whether your horse truly requires concentrated feeds based on workload and body condition.

Ensuring Constant Fresh Water Access

Maintain clean, palatable water sources available at all times. Check water supplies multiple times daily, breaking ice in winter and keeping water cool in summer. Some horses prefer different water sources, so provide options when possible.

Monitor individual water consumption patterns, noting any decreases that might signal developing problems. Electrolyte supplementation during hot weather or after exercise encourages drinking and maintains hydration.

Implementing Regular Dental and Parasite Control

Schedule dental examinations and floating at least annually, or more frequently for older horses or those with known dental issues. Proper dental function ensures effective chewing and appropriate feed particle size entering the digestive system.

Follow veterinarian-recommended deworming protocols based on fecal egg counts rather than automatic scheduled treatments. This strategic approach targets parasite burdens effectively while minimizing drug resistance development.

Supporting Regular Exercise and Movement

Daily turnout allows natural movement patterns, grazing behavior, and social interaction that support normal digestive function. Exercise promotes gut motility, encourages water consumption, and reduces stress levels.

Horses confined to stalls for extended periods face elevated risk compared to those with regular pasture access. When stall confinement becomes necessary, provide maximum safe turnout time and hand-walking or controlled exercise.

Minimizing Environmental Stress

Maintain consistent routines regarding feeding times, turnout schedules, and handling practices. Introduce changes gradually, whether relocating to new facilities, changing companions, or modifying training programs.

Recognize that competition, trailering, and environmental changes create stress even for experienced horses. Support horses during stressful periods with familiar routines, adequate rest, and careful monitoring for early distress signs.

Conclusion: Vigilance and Prompt Action Save Equine Lives

Abdominal pain in horses demands respect as a potentially life-threatening emergency requiring immediate professional intervention. Understanding the diverse causes, recognizing symptom progression from mild to severe, and implementing appropriate emergency responses empower horse owners to protect their animals effectively.

Prevention through consistent management practices, regular veterinary care, proper nutrition, and stress minimization significantly reduces occurrence rates. However, even the best management cannot eliminate all risk, making owner education and preparedness essential components of responsible horse ownership.

Establish relationships with equine veterinarians before emergencies arise, maintain updated contact information, and develop emergency action plans. Quick recognition and rapid veterinary response provide the best opportunity for positive outcomes, whether through successful medical management or timely surgical intervention.

Your horse’s life may depend on your ability to recognize distress signals and act decisively. Stay informed, remain vigilant, and never hesitate to seek professional help when abdominal pain symptoms appear.