From Symptoms, Pathogenesis, Treatment & Prevention

Listeriosis strikes fear into the hearts of goat farmers worldwide. This bacterial infection, caused by Listeria monocytogenes, attacks the nervous system and can devastate entire herds within days. Listeriosis, also known as “circling disease” or “silage sickness,” is a serious bacterial infection in goats caused by the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. It primarily manifests in an encephalitic (brain infection) form, which is often fatal, or as an abortive (miscarriage) or septicemic (blood poisoning) disease. Understanding this disease saves lives and protects your investment in your animals.

What Is Listeriosis in Goats? Understanding the Circling Disease

Listeriosis represents a serious bacterial infection that primarily affects goats and other small ruminants. The bacterium Listeria monocytogenes invades the body through contaminated feed, causing three distinct forms of disease: neurological complications, septicemic infections, and reproductive failures.

Veterinarians commonly call this condition “circling disease” because infected goats walk in tight circles, unable to control their movements. The infection spreads rapidly through herds, especially during winter months when farmers rely heavily on stored silage for feeding.

The disease affects goats of all ages, though young animals between six months and three years face the highest risk. Adult breeding does also show increased vulnerability, particularly during late pregnancy when stress levels peak.

How Listeria Monocytogenes Infects Your Herd

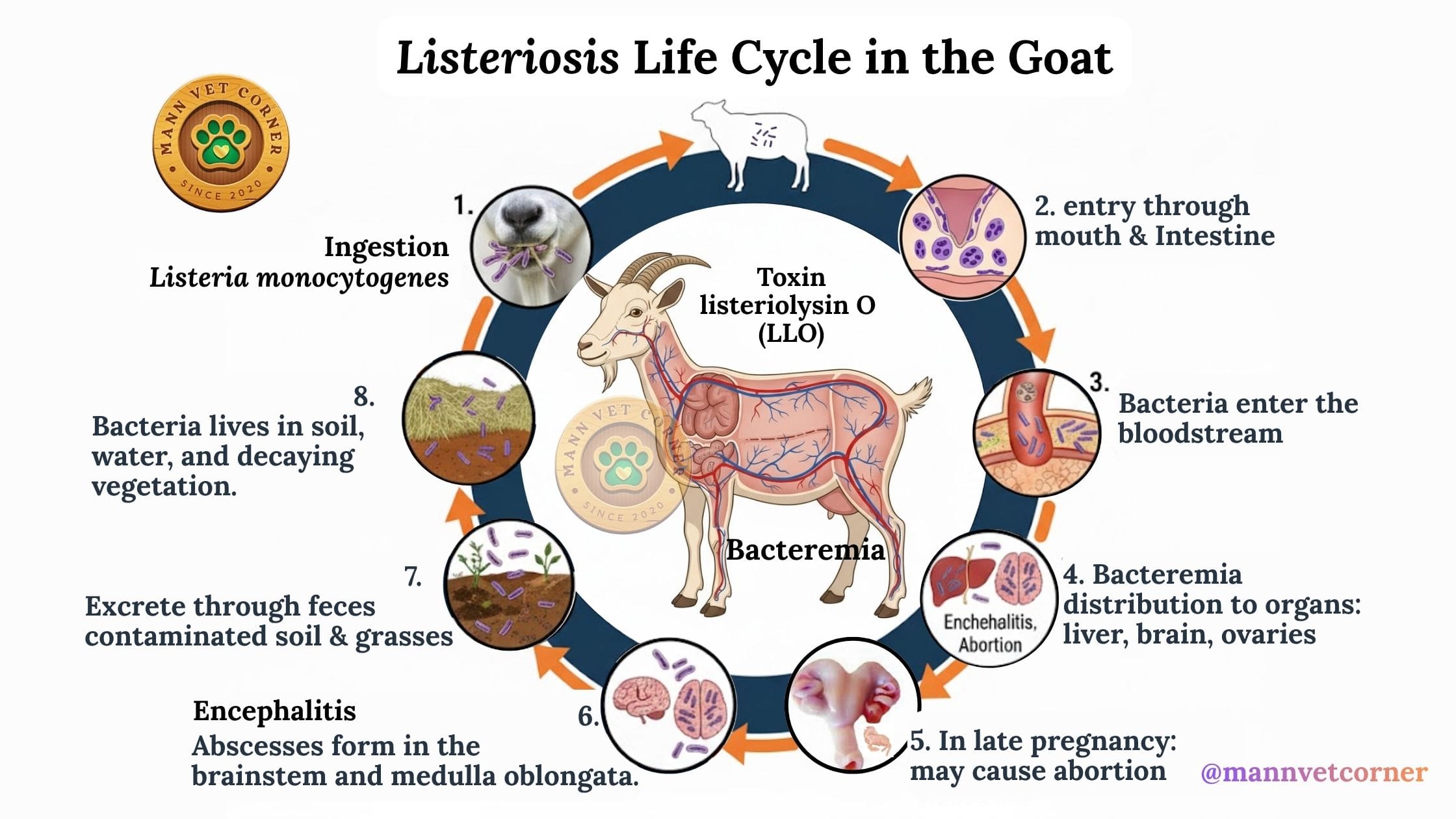

Listeria monocytogenes thrives in soil, water, and plant material throughout the environment. The bacteria survive extreme conditions, including freezing temperatures and high pH levels in improperly fermented silage.

Goats contract listeriosis primarily through consuming contaminated feed. Poorly preserved silage with pH levels above 5.0 creates perfect breeding grounds for bacterial multiplication. The organisms enter the bloodstream through tiny wounds in the mouth or through the intestinal lining.

Once inside the body, the bacteria travel to the brainstem, causing the characteristic neurological symptoms farmers dread. In pregnant does, the organisms cross the placental barrier, leading to fetal infections and spontaneous abortions.

Clinical Signs of Listeriosis in Small Ruminants: What to Watch For

Recognition of early symptoms determines whether your goat survives or succumbs to this aggressive infection. The clinical presentation varies depending on which body system the bacteria attack first.

Neurological Form: The Classic Circling Disease in Goats

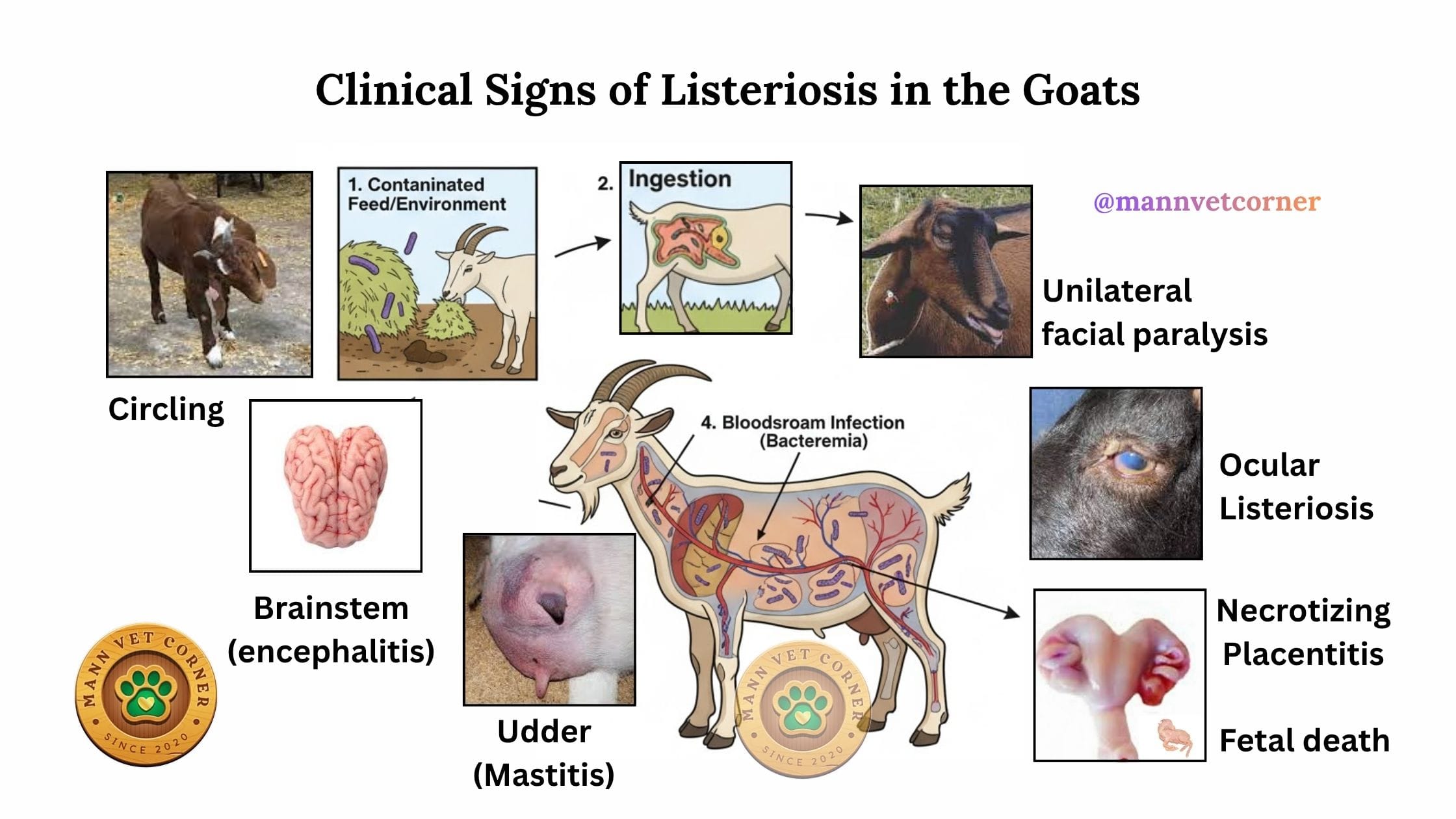

The neurological manifestation produces the most recognizable symptoms. Affected goats display unilateral facial paralysis, causing one ear to droop and one eyelid to sag. Farmers notice their animals walking in tight circles, always turning toward the affected side of the brain.

Depression sets in rapidly. Goats separate themselves from the herd, standing motionless with their heads pressed against walls or fences. They lose their appetite completely and stop ruminating, leading to rapid weight loss.

As the infection progresses, animals develop severe incoordination. They stumble, fall, and eventually lose the ability to stand. Without prompt treatment, death follows within four to fourteen days after symptoms appear.

Ocular Listeriosis: Understanding Silage Eye in Goats

Ocular listeriosis, widely known as “silage eye,” affects one or both eyes. Infected goats squint constantly, produce excessive tears, and show extreme sensitivity to light. The cornea develops a characteristic cloudy appearance, and untreated cases progress to blindness.

This form develops when bacteria enter through conjunctival tissues or migrate from the brainstem through cranial nerves. Young animals suffer most frequently from this manifestation, particularly when farms feed moldy or poorly fermented silage.

The condition causes severe pain. Affected goats refuse to eat, lose weight rapidly, and their milk production drops dramatically if they’re lactating.

Abortion in Listeriosis: Reproductive Losses That Devastate Herds

Pregnant does carrying kids in the last trimester face the greatest abortion risk. Listeriosis triggers sudden pregnancy losses without any preceding warning signs. Does appear completely healthy one day, then abort dead or weak kids the next.

The infection crosses the placental barrier during bacteremia, directly invading fetal tissues. Kids born alive from infected mothers rarely survive more than a few days, despite aggressive treatment attempts.

Farmers report retained placentas occurring frequently after listeriosis-induced abortions. The does themselves often develop metritis and other secondary reproductive complications that affect future breeding success.

Septicemic Form: When Listeriosis Causes Bacteremia

The septicemic manifestation strikes suddenly, offering little warning before death occurs. Young kids, particularly those under three months old, develop this form most commonly.

Affected animals show severe depression, refuse milk or feed, and their body temperatures spike dramatically. Diarrhea develops rapidly, leading to severe dehydration. Most kids die within 24 to 48 hours after symptoms begin, often before owners can implement treatment.

Post-mortem examination reveals widespread bacterial invasion throughout the body, affecting the liver, spleen, and other vital organs.

Paralysis in Goat Listeriosis: Progressive Muscle Weakness

Some goats develop ascending paralysis that begins in the hindquarters and moves forward. The legs become progressively weaker until the animal can no longer stand. This presentation confuses farmers because it mimics other neurological conditions like goat polio or spinal injuries.

The paralysis differs from other causes because it advances rapidly and accompanies other listeriosis symptoms like facial nerve damage or circling behavior. Affected goats maintain consciousness and awareness even as they lose all motor control.

Listeriosis Incubation Period: When Symptoms Appear After Exposure

Understanding the timeline between exposure and symptom development helps farmers identify the source of infection and prevent additional cases.

The incubation period typically ranges from one to three weeks after consuming contaminated feed. However, stress factors like kidding, transport, or sudden weather changes can shorten this period dramatically.

Neurological symptoms appear first in most cases, developing over just one to three days. The animal seems perfectly normal one morning, then shows obvious signs of brain infection by evening. This rapid progression catches owners off guard and limits treatment opportunities.

In pregnant does, the incubation period extends longer, sometimes lasting four to six weeks before abortion occurs. The bacteria multiply slowly in the placenta before reaching fatal concentrations that kill the developing kids.

Pathogenesis of Listeriosis: How the Disease Progresses in Goats

The disease progression follows a predictable pattern once bacteria enter the goat’s body. Understanding this sequence helps explain why treatment succeeds or fails.

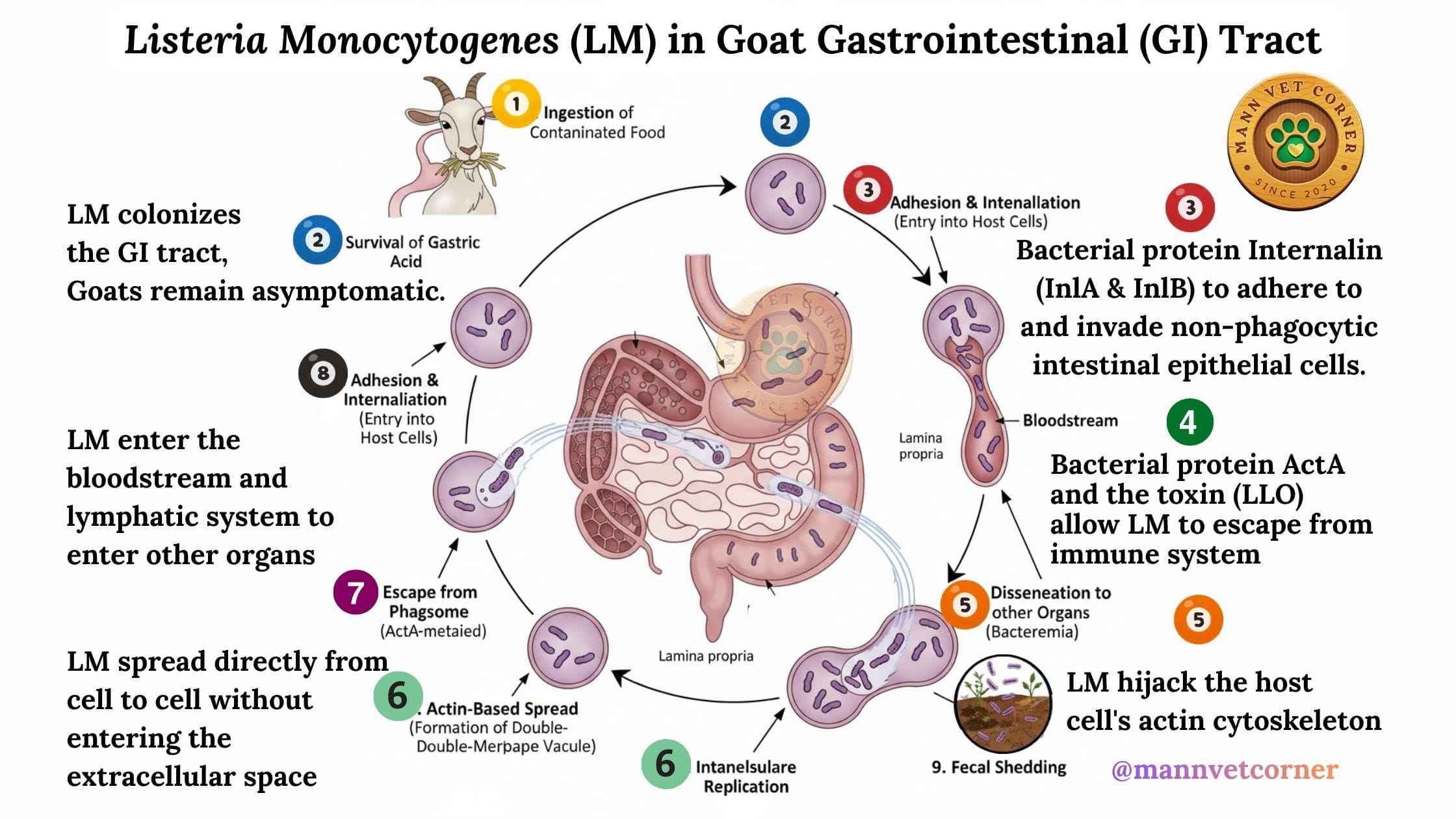

Listeria monocytogenes initially colonizes the intestinal tract after ingestion. The bacteria pass through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream, causing transient bacteremia. Most healthy goats with strong immune systems eliminate the organisms at this stage, showing no symptoms whatsoever.

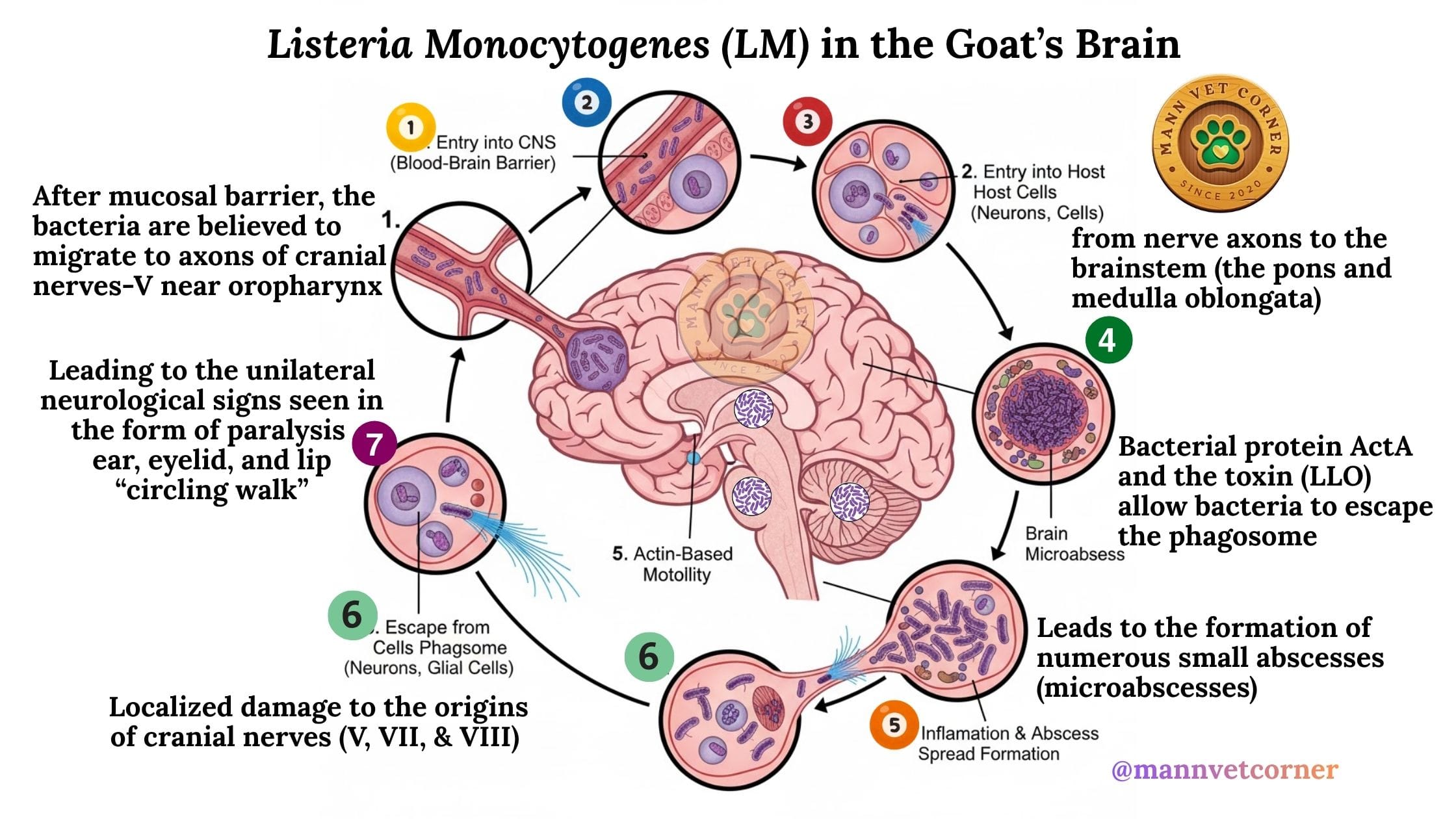

When immune systems fail to clear the infection, bacteria migrate to target organs. In neurological cases, the organisms travel through cranial nerves or cross the blood-brain barrier, reaching the brainstem. There they multiply rapidly, causing inflammation, abscesses, and tissue death.

The facial nerve runs through the brainstem, explaining why facial paralysis appears so consistently. As inflammation spreads, it affects the animal’s balance centers, motor control regions, and coordination pathways.

In pregnant does, bacteria circulating in the bloodstream cross into the uterus. They infect the placenta first, then move into fetal circulation. The kids’ immature immune systems cannot fight the invasion, leading to fetal death and subsequent abortion.

Invasion of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT)

- Survival in the GIT Environment: Listeria is primarily ingested through contaminated feed, especially poor-quality silage with a pH above 5.5. The bacteria must survive the acidic conditions of the stomach and the presence of bile in the intestines. They use systems like the glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) and arginine deiminase (ADI) pathways for acid tolerance, and bile salt hydrolase (Bsh) for bile resistance.

- Adhesion and Internalization: Once past the initial barriers, Listeria adheres to the surface of intestinal epithelial cells. Key bacterial proteins, called internalins (InlA and InlB), interact with host cell receptors E-cadherin and c-Met, respectively. This interaction induces changes in the host cell’s structure, causing the cell to engulf the bacterium (internalization). Another protein, Listeria Adhesion Protein (LAP), can also mediate entry by disrupting host cell junctions.

- Intracellular Survival and Spread: Inside the host cell, the bacterium escapes from the phagocytic vacuole into the cytoplasm by producing a pore-forming toxin called listeriolysin O (LLO). Once in the cytoplasm, Listeria multiplies and uses the host cell’s actin cytoskeleton (via the ActA protein) to move and spread directly to adjacent cells, thus evading the host’s immune system.

- Dissemination: After crossing the intestinal barrier, the bacteria enter the bloodstream and lymphatic system, traveling to primary target organs like the liver and spleen. In immunocompromised animals (e.g., pregnant goats), the bacteria can then cross the blood-brain barrier, leading to encephalitis (circling disease), or the placental barrier, causing abortion.

Invasion of the central nervous system (CNS)

- Initial infection: Goats most commonly become infected by ingesting the bacteria from contaminated sources like spoiled silage, decaying vegetation, or contaminated feed.

- Gastrointestinal colonization: After ingestion, L. monocytogenes colonizes the gut and can invade the bloodstream, but in ruminants, it frequently takes a neural route to the brain.

- Neural ascent: The bacteria gain access to the CNS by ascending the trigeminal nerve, which has its origin in the brainstem.

- Meningoencephalitis: This leads to a localized, asymmetric infection of the brainstem, causing a meningoencephalitis that damages cranial nerves V, VII, and VIII.

- Clinical signs: The damage to these nerves results in typical clinical signs such as unilateral facial paralysis, head tilt, circling, and depression.

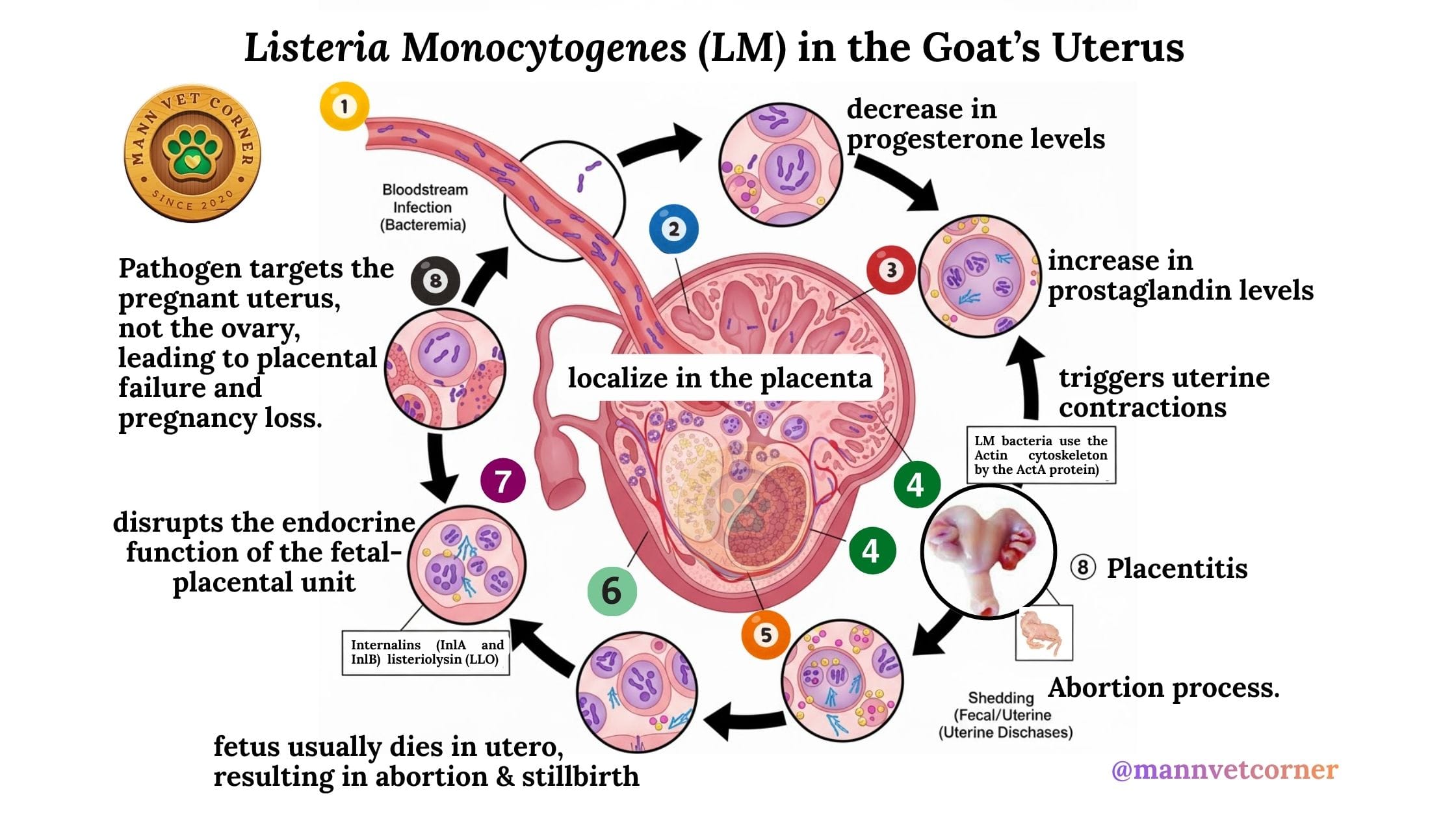

Invasion of the Placenta & Uterus

Listeria spreads to the uterus and placenta via the bloodstream after initial ingestion of contaminated food or water. The bacteria exploit specific host cell pathways to cross biological barriers. Listeria uses its surface proteins, internalin A (InlA) and internalin B (InlB), to interact with the host proteins E-cadherin and c-Met, respectively. This interaction facilitates the invasion of uterine epithelial cells and crossing of the placental barrier.

Once inside the uterine and placental cells, the bacterium produces a virulence factor called listeriolysin O (LLO), which helps it escape from the host cell’s internal defense mechanisms and survive and multiply within the cells.

- Placentitis: The infection causes severe, diffuse necrotizing and suppurative (pus-forming) placentitis, affecting both the cotyledons and the intercotyledonary areas.

- Cellular effects: The infection triggers increased apoptosis (programmed cell death) and autophagy (cellular self-digestion) in the uterine cells, disrupting tissue homeostasis.

- Fetal death: The damage to the placenta compromises the transfer of nutrients to the fetus, leading to fetal death in utero, stillbirths, or the birth of weak kids.

- Maternal illness: While does often show no other symptoms before aborting, they may develop severe metritis (uterine inflammation) afterward and can shed the bacteria in uterine discharges and milk for a month or longer.

Postmortem Findings in Listeriosis: What Necropsy Reveals

Veterinary examination of deceased animals provides crucial diagnostic information and confirms listeriosis as the cause of death.

Brain and Nervous System Changes

The brainstem shows characteristic microabscesses visible under microscopic examination. These tiny pockets of infection appear as yellowish spots throughout the tissue. The surrounding brain matter displays inflammation and hemorrhaging in severe cases.

Veterinarians find the trigeminal nerve roots particularly affected. Swelling and inflammation in these structures explain the facial paralysis and loss of sensation animals experience.

The meninges (protective membranes covering the brain) show inflammation and increased fluid accumulation. This meningitis contributes to the severe depression and behavioral changes owners observe.

Aborted Fetuses and Placental Examination

Examination of aborted kids reveals widespread bacterial colonization. The liver appears enlarged and shows multiple small abscesses scattered throughout the tissue. The spleen similarly displays enlargement and focal infection points.

The placenta demonstrates severe inflammation with areas of tissue death. Bacterial cultures from placental tissue consistently grow Listeria monocytogenes, confirming the diagnosis.

Septicemic Cases: Whole-Body Bacterial Invasion

Kids dying from septicemic listeriosis show bacterial infection throughout multiple organs. The liver displays the most obvious changes, with numerous small abscesses visible on both the surface and interior.

The spleen enlarges dramatically, sometimes doubling or tripling normal size. The intestinal tract shows inflammation and hemorrhaging, explaining the severe diarrhea these animals experience.

Veterinarians often find bacteria in the lungs, kidneys, and heart muscle, indicating the widespread nature of the infection.

Diagnosing Listeriosis in Your Goat Herd

Accurate diagnosis requires combining clinical observations with laboratory confirmation. Your veterinarian needs specific information to differentiate listeriosis from similar diseases.

Clinical Diagnosis Based on Symptoms

Experienced veterinarians recognize listeriosis based on the characteristic symptom pattern. The combination of unilateral facial paralysis, circling behavior, and depression strongly suggests listeriosis, especially when multiple animals show symptoms within a short timeframe.

The history matters tremendously. Herds receiving poor-quality silage within the past few weeks raise immediate suspicion for listeriosis. The disease rarely affects animals on pasture during summer months.

Laboratory Testing for Confirmation

Bacterial culture provides definitive diagnosis. Your veterinarian collects cerebrospinal fluid through spinal tap in live animals or brain tissue samples from deceased goats. The laboratory grows Listeria monocytogenes from these samples, confirming the diagnosis.

Blood cultures help diagnose septicemic cases. The laboratory detects bacteria circulating in the bloodstream, though results take several days to return. This delay means veterinarians must begin treatment before confirmation arrives.

Aborted fetuses and placentas yield positive cultures in reproductive cases. The laboratory isolates bacteria from fetal stomach contents, liver tissue, and placental samples.

Ruling Out Similar Diseases

Several conditions mimic listeriosis symptoms, requiring careful differentiation:

Polioencephalomalacia (goat polio) causes circling and neurological symptoms but typically produces blindness and different brain lesions on necropsy.

Meningeal worm infection creates similar neurological signs but progresses more slowly and responds to different treatments.

Rabies must be ruled out in any goat showing neurological symptoms to protect human health, though rabies typically causes aggression rather than depression.

Caprine arthritis encephalitis virus damages the nervous system but develops gradually over weeks or months, unlike listeriosis’s rapid onset.

Treatment of Listeriosis in Goats: Can You Save Infected Animals?

Treatment success depends entirely on how quickly you recognize symptoms and begin aggressive therapy. Every hour counts when battling this infection.

Antibiotic Therapy: First Line of Defense

High-dose antibiotic treatment forms the cornerstone of listeriosis management. Your veterinarian will prescribe specific antibiotics that cross the blood-brain barrier effectively.

Oxytetracycline works well when administered early in the disease course. Veterinarians inject 20 mg per kilogram of body weight intravenously once daily for at least five consecutive days. Some cases require treatment extension to seven or ten days.

Penicillin remains the gold standard for listeriosis treatment. Veterinarians prescribe 40,000 to 80,000 units per kilogram intramuscularly twice daily. Treatment must continue for minimum seven days, though many practitioners extend therapy to two full weeks.

Chloramphenicol serves as an alternative when other antibiotics fail. This medication penetrates nervous tissue exceptionally well but requires careful handling due to human health concerns.

Starting treatment within the first 24 to 48 hours after symptoms appear dramatically improves survival rates. Goats treated after day three of illness rarely recover fully, even with aggressive intervention.

Supportive Care: Keeping Animals Alive During Treatment

Antibiotics alone won’t save your goat. Comprehensive supportive care prevents complications and maintains body condition during recovery.

Fluid therapy prevents dehydration, particularly in animals unable to drink normally. Subcutaneous or intravenous fluids maintain hydration and support kidney function. Administer two to four liters daily depending on the animal’s size and dehydration level.

Nutritional support keeps animals from starving during their illness. Goats with listeriosis stop eating completely. Tube feeding with electrolyte solutions, milk replacer, or gruel provides essential calories and nutrients. Feed small amounts frequently rather than large volumes at once.

Anti-inflammatory medications reduce brain swelling and inflammation. Your veterinarian may prescribe flunixin meglumine or dexamethasone to decrease pressure inside the skull and improve comfort.

Nursing care makes the difference between life and death. Move affected animals to a quiet, deeply bedded area away from herd stress. Turn recumbent goats every four to six hours to prevent pressure sores and pneumonia. Keep them clean, dry, and comfortable.

Treatment Success Rates and Prognosis

Honest conversations about survival chances help owners make informed decisions. Treatment outcomes vary dramatically based on several factors:

Animals treated within 24 hours of symptom onset show 50 to 70 percent survival rates with aggressive therapy. Those treated after 48 hours rarely survive, and survivors often retain permanent neurological damage.

Young, healthy goats respond better than older or compromised animals. Does in late pregnancy rarely survive, and even if they do, they typically abort their kids.

The extent of neurological damage determines long-term outcomes. Goats recovering from listeriosis may retain facial paralysis, reduced coordination, or blindness. These animals rarely return to full productivity and may require culling on humane grounds.

Prevention of Listeriosis: Protecting Your Herd from Infection

Prevention strategies prove far more effective and cost-efficient than treating disease outbreaks. Implementing comprehensive management practices eliminates most listeriosis risk.

Silage Management: The Most Critical Prevention Factor

Poor silage quality causes the majority of listeriosis outbreaks in goats. Proper fermentation creates an acidic environment that inhibits Listeria growth.

Achieve proper fermentation by ensuring silage pH drops below 5.0 within the first few days after ensiling. Test pH regularly using simple meter devices available at farm supply stores.

Fill silos rapidly to minimize air exposure during the filling process. Complete filling within two to three days maximum. Air pockets in silage allow bacterial multiplication and spoilage.

Pack silage tightly to exclude oxygen. Use appropriate equipment and weight to compress material thoroughly. Well-packed silage resists spoilage and maintains quality throughout the feeding period.

Cover silage immediately after filling completes. Use plastic sheeting weighted with tires or sandbags to create an airtight seal. This prevents surface spoilage and contamination.

Discard moldy or spoiled silage without hesitation. Never feed goats any silage showing visible mold, heating, or foul odors. The cost of replacing feed pales compared to treating listeriosis outbreaks.

Remove silage face carefully when feeding. Take silage from the top downward in thin layers, keeping the face smooth and vertical. This minimizes air exposure and prevents surface deterioration.

Feed Quality and Storage Practices

All stored feeds require attention to prevent Listeria contamination, not just silage.

Store hay properly in dry, well-ventilated areas protected from moisture. Wet hay encourages mold growth and bacterial multiplication. Never feed moldy or dusty hay to goats under any circumstances.

Maintain clean feeding areas by removing leftover feed daily. Contaminated feed dropped on the ground collects soil bacteria and should never be re-fed.

Provide clean water at all times. Stagnant water sources harbor bacteria and increase infection risk. Clean water troughs weekly and provide fresh water daily.

Stress Reduction: Strengthening Immune Defenses

Stress suppresses immune function, allowing Listeria bacteria to establish infections that healthy immune systems would eliminate.

Minimize handling and transport during late pregnancy. Does approaching kidding face tremendous physiological stress. Avoid unnecessary procedures, moves, or changes during this vulnerable period.

Maintain consistent feeding schedules to reduce digestive stress. Sudden diet changes upset rumen function and compromise immune responses.

Provide adequate shelter from extreme weather conditions. Cold stress and rain exposure weaken animals and increase susceptibility to infection.

Control parasites effectively through regular fecal testing and strategic deworming. Parasite burdens drain nutrients and suppress immunity.

Biosecurity Measures to Prevent Introduction

Listeria bacteria exist everywhere in the environment, but certain practices reduce herd exposure dramatically.

Quarantine new animals for minimum 30 days before introducing them to your herd. Observe carefully for any signs of illness during this period.

Control wildlife access to feed storage areas. Birds, rodents, and wild animals contaminate stored feed with feces carrying various pathogens.

Maintain clean kidding areas by removing soiled bedding frequently and providing fresh, dry material for does preparing to deliver.

Separate sick animals immediately when you notice symptoms. Infected goats shed bacteria in saliva, feces, and aborted materials, contaminating the environment and spreading disease.

Vaccination: Is There a Listeriosis Vaccine for Goats?

Currently, no commercial vaccine prevents listeriosis in goats. Research continues on vaccine development, but nothing has achieved regulatory approval for use in small ruminants.

Some farmers attempt vaccination using bacterins (killed bacterial vaccines), but these products show limited effectiveness. The bacteria invade cells, making it difficult for antibodies produced by vaccination to access and neutralize them.

Focus prevention efforts on management practices rather than hoping for vaccine protection.

Special Considerations for Different Production Systems

Production system affects listeriosis risk substantially. Tailor your prevention strategies to match your specific operation.

Dairy Goat Operations: Additional Concerns

Dairy operations face unique challenges because lactating does require high-energy diets typically including large amounts of silage.

Test silage quality rigorously before feeding to milking does. Send samples to laboratories for pH testing, mold counts, and bacterial culture if you suspect problems.

Monitor milk production carefully for sudden drops. Listeriosis causes dramatic production decreases before other symptoms become obvious. Investigate any unexplained production decline immediately.

Maintain strict milking hygiene to prevent udder infections that could complicate listeriosis cases. Infected animals already face tremendous stress; adding mastitis often proves fatal.

Meat Goat Production: Managing Large Herds

Commercial meat operations grazing large numbers of goats face different management challenges.

Provide supplemental feed carefully during winter months. If you must use silage or stored feeds, inspect quality meticulously before distributing to the herd.

Monitor animals closely during feeding times when you can observe the entire group. Early detection of affected individuals allows prompt separation and treatment.

Consider pasture management strategies that reduce reliance on stored feeds. Extended grazing seasons and stockpiled forage decrease listeriosis risk substantially.

Fiber Goat Management: Protecting Breeding Stock

Angora and cashmere operations depend heavily on their breeding stock quality and productivity.

Time shearing carefully to avoid creating additional stress during late pregnancy or extreme weather conditions. Combined stressors dramatically increase disease susceptibility.

Provide extra nutrition during harsh weather when fiber goats face tremendous energy demands for both fetal development and fiber production.

Maintain detailed breeding records to identify does in late pregnancy needing extra monitoring and care during high-risk periods.

Frequently Asked Questions About Listeriosis in Goats

Can humans catch listeriosis from infected goats?

Yes, humans can contract listeriosis, though transmission from goats to people occurs rarely. The bacteria spread primarily through consuming contaminated food products, particularly unpasteurized milk and soft cheeses.

Pregnant face the greatest risk from listeriosis because the infection causes miscarriage and fetal death. Anyone with weakened immune systems should avoid contact with sick animals and never consume raw milk from any source.

Always wear gloves when handling aborted fetuses or placental material from infected does. Wash hands thoroughly after working with sick animals. These simple precautions prevent virtually all transmission risks.

How long does Listeria monocytogenes survive in the environment?

These hardy bacteria persist for months or even years in soil, bedding, and contaminated equipment. They survive freezing temperatures, making them particularly dangerous in stored winter feeds.

The organisms thrive in pH ranges from 4.4 to 9.6, which explains why improperly fermented silage supports bacterial growth. Only extremely acidic environments (pH below 4.0) or high heat eliminate Listeria effectively.

Thorough cleaning and disinfection using appropriate products kills bacteria on equipment and surfaces. However, environmental contamination remains essentially permanent, emphasizing the critical importance of prevention.

Should I cull goats that recover from neurological listeriosis?

This difficult decision depends on the extent of permanent damage and your operation’s goals. Goats retaining severe facial paralysis struggle to eat effectively and lose body condition chronically. These animals rarely return to acceptable productivity levels.

Animals with minor residual effects may function adequately in breeding programs, though they shouldn’t enter show rings or sales. Evaluate each case individually, considering the animal’s genetic value against ongoing care requirements.

From a practical standpoint, recovered animals shed bacteria intermittently, potentially spreading disease to susceptible herdmates. Many veterinarians recommend culling recovered animals to eliminate this risk.

What’s the difference between listeriosis and goat polio?

These two conditions cause similar circling behavior and neurological symptoms but result from completely different causes. Polioencephalomalacia (goat polio) develops from thiamine deficiency, while listeriosis comes from bacterial infection.

Goat polio typically causes blindness with dilated pupils that don’t respond to light. Listeriosis rarely affects vision in neurological cases (except for the specific ocular form). Goat polio responds dramatically to thiamine injections within hours, while listeriosis requires prolonged antibiotic therapy.

Post-mortem examination easily differentiates these diseases. Goat polio creates distinctive yellow-brown discoloration in the brain visible to the naked eye, while listeriosis produces microscopic abscesses requiring laboratory examination.

Can goats develop immunity after recovering from listeriosis?

Animals surviving listeriosis may develop some level of immunity, though research on this topic remains limited. The immunity likely proves partial and short-lived, failing to protect against subsequent exposures completely.

Don’t rely on natural immunity to protect your herd. Recovered animals still face reinfection risks, particularly during stressful periods or when exposed to heavily contaminated feed sources.

How quickly should I expect improvement with antibiotic treatment?

Goats responding to treatment typically show subtle improvement within 48 to 72 hours. The fever drops, appetite returns slightly, and alertness increases. However, dramatic recovery takes one to two weeks minimum.

Animals showing no improvement after three days of aggressive therapy carry a poor prognosis. Continue treatment for the full course regardless, as some goats demonstrate delayed responses.

Neurological deficits improve slowly over weeks or months. Facial paralysis may resolve partially but rarely disappears completely. Set realistic expectations with your veterinarian about recovery timelines and anticipated outcomes.

Should I treat the entire herd if one goat develops listeriosis?

Veterinarians debate this question extensively. Some practitioners recommend treating all animals consuming the same contaminated feed source, while others treat only symptomatic individuals.

The decision depends on several factors: how many animals show symptoms, the quality of feed available, and your herd’s overall health status. Discuss this with your veterinarian to develop an appropriate strategy for your specific situation.

At minimum, remove suspect feed immediately and monitor all herd members closely for developing symptoms. Early detection and treatment save lives.

Can I continue drinking milk from goats on listeriosis treatment?

Never consume raw milk from animals under antibiotic treatment. Federal regulations prohibit this practice, and drugs concentrate in milk, creating human health risks.

Each antibiotic carries a specific withdrawal period—the time required after the last treatment before milk becomes safe for consumption. For penicillin, this period extends 60 hours after the final injection. Oxytetracycline requires 96 hours withdrawal.

Your veterinarian provides specific guidance on withdrawal periods for medications prescribed. Mark treated animals clearly and keep detailed treatment records to prevent accidental milk consumption during withdrawal.

Pasteurization kills Listeria bacteria, making properly pasteurized milk safe for consumption. However, antibiotic residues survive pasteurization, so withdrawal periods still apply.

Taking Action: Your Next Steps for Herd Protection

Listeriosis threatens every goat operation, but understanding this disease empowers you to protect your animals effectively. Focus your efforts on feed quality management, stress reduction, and early disease detection.

Walk through your feed storage areas today. Examine silage for signs of spoilage, check hay for mold, and ensure water sources stay clean. These simple steps prevent most listeriosis cases before they start.

Develop relationships with veterinarians experienced in small ruminant medicine. Having professional support available when emergencies strike makes the difference between losing animals and saving them.

Remember that prevention always costs less than treatment. Investing time and resources in proper management practices protects your herd’s health and your operation’s profitability for years to come.