Cattle Botfly Infestation

Bot flies are a group of parasitic flies that threaten livestock health and farm productivity in worldwide. These flies cause significant losses in meat and leather production, affecting farmers’ profitability and animal welfare. Cattle botfly infestation, also known as warble fly infestation (Warbles is a bumps under the skin that are caused by infection with fly larvae), occurs when female botflies lay eggs on cattle. This comprehensive guide explores everything cattle farmers need to know about botfly management from Signs, Life Cycle, Pathogenesis, Treatment & Prevention

What Are Cattle Botflies and Why Do They Matter to Livestock Producers?

Cattle botflies belong to the family Oestridae, with three primary species causing problems in cattle herds. Hypoderma lineatum (common cattle grub) and Hypoderma bovis (northern cattle grub) attack cattle across North America, Europe, and Asia. These parasites create painful lesions, reduce weight gain, and damage valuable hides.

The economic importance of cattle botflies extends beyond immediate health concerns. Infested cattle experience reduced milk production, decreased feed efficiency, and slower growth rates. Hide damage from warble holes can reduce leather value by 30-50 percent, costing the industry millions annually.

Complete Life Cycle of Cattle Botflies: From Egg to Adult Fly

How Cattle Botflies Reproduce and Infest Livestock Herds

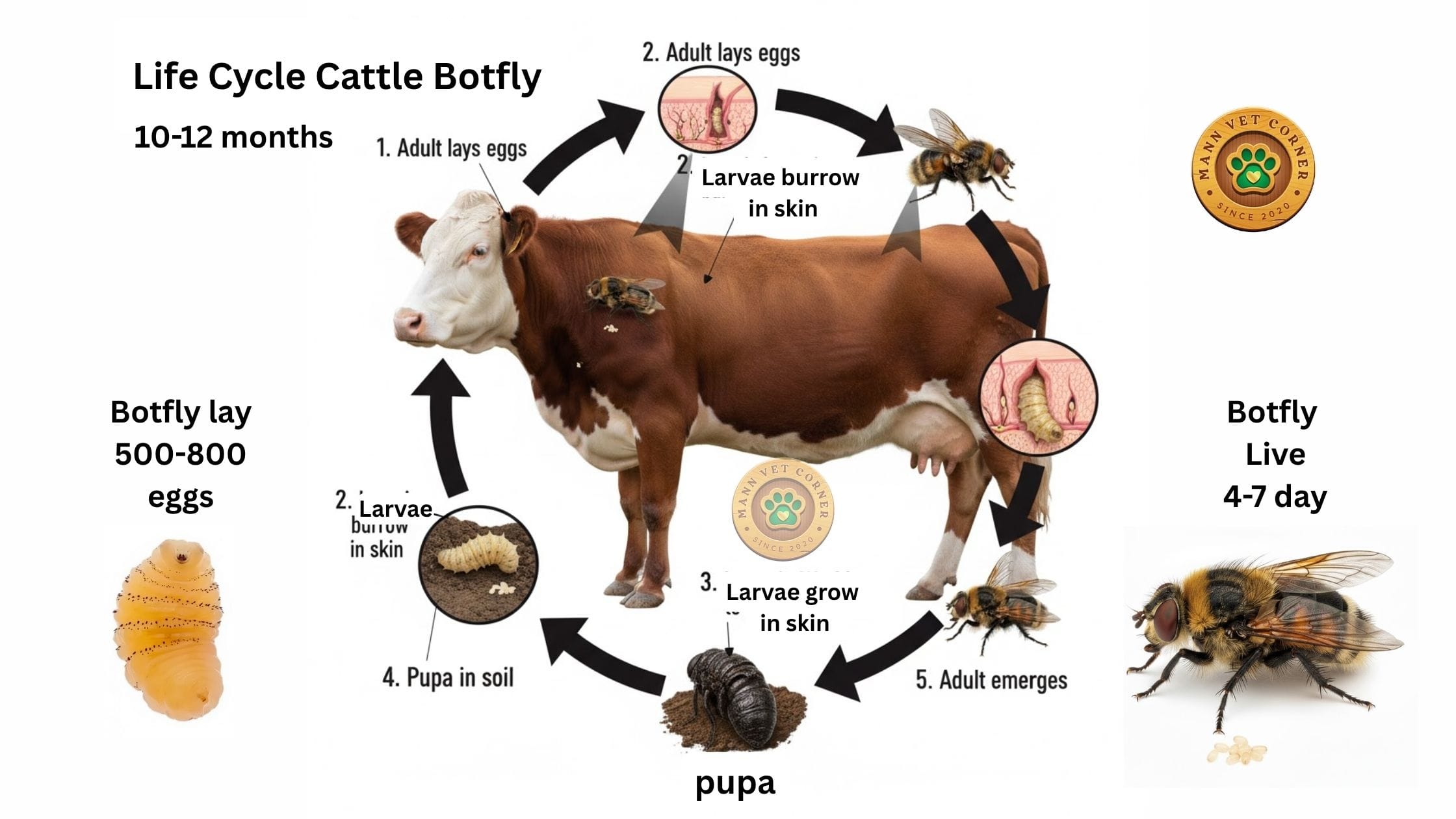

Cattle botfly infestation, also known as warble fly infestation, occurs when female botflies lay eggs on cattle. The larvae hatch, penetrate the skin, and migrate through the body, developing in lumps called “warbles” under the skin on the animal. These warbles have a small hole for breathing, and eventually, the mature larvae emerge, fall to the ground, pupate, and develop into adult flies.

Adult female botflies emerge during warm months, typically from May through August in temperate regions. These flies live for only 3-7 days but can lay 500-800 eggs during their brief lifespan. Unlike many biting flies, adult botflies do not feed.

Female Hypoderma lineatum flies attach eggs to cattle leg hairs, while H. bovis prefers heel hairs. The attached eggs remain dormant for 3-7 days before hatching. This egg-laying process terrifies cattle, causing them to run wildly—a behavior called “gadding” that results in injuries and reduced grazing time.

Cattle Botfly Incubation Period and Larval Development Timeline

The incubation period for cattle botfly (Hypoderma species, also known as warble flies) eggs is typically 3 to 7 days. The incubation period varies depending on environmental temperature and humidity. Eggs typically hatch within 4-7 days when conditions favor development. Newly hatched first-stage larvae (L1) penetrate the skin at the attachment site and begin their remarkable migration through the host.

First-stage larvae travel through connective tissues for 3-4 months. H. lineatum larvae migrate to the esophagus wall, while H. bovis larvae journey to the spinal canal region. This migration period represents the most dangerous phase for cattle health.

After spending several months in these intermediate sites, larvae molt to the second stage (L2) and migrate toward the back. Second-stage larvae arrive beneath the back skin during winter months, where they create characteristic breathing holes called warbles.

Understanding Warble Formation and Third-Stage Larval Development

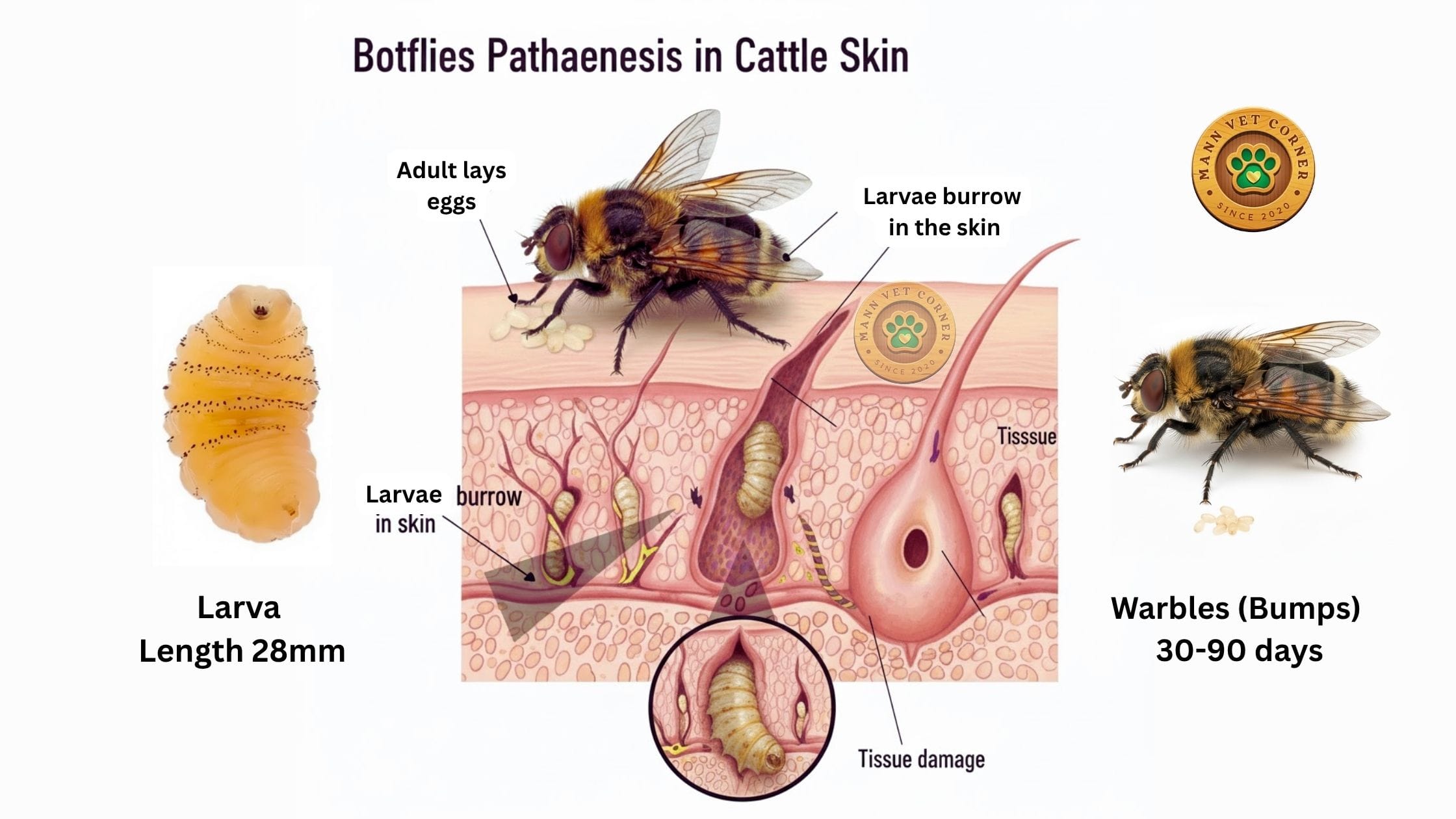

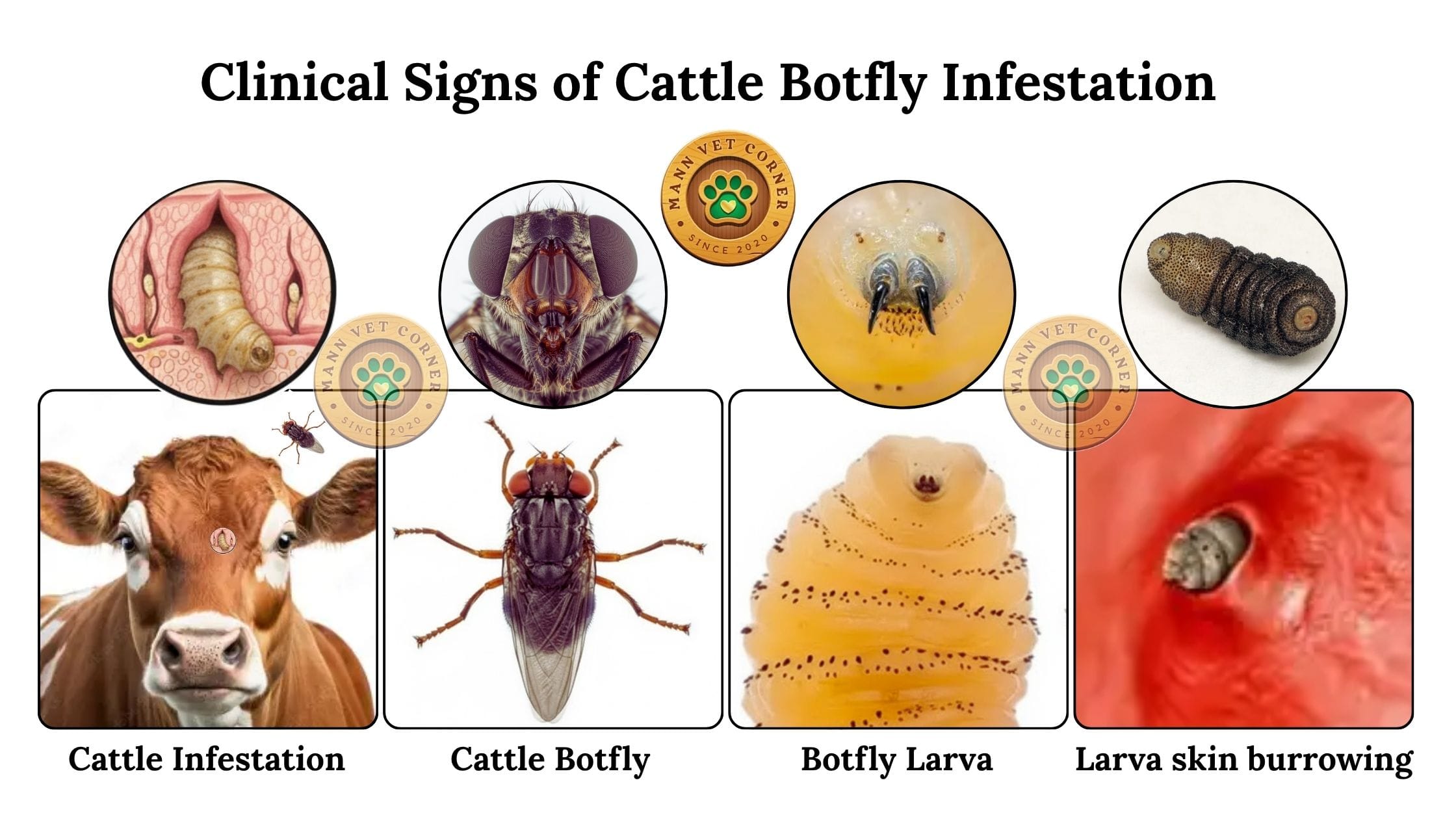

Third-stage larvae (L3) develop within warbles for 30-90 days, depending on temperature. These large, grub-like larvae measure up to 28 millimeters long. Each larva creates a cyst beneath the skin, causing swelling, pain, and tissue destruction.

During late winter and spring, mature third-stage larvae emerge through breathing holes and drop to the ground. Once on soil, larvae pupate within 24-48 hours. The pupal stage lasts 3-8 weeks before adult flies emerge, completing the one-year life cycle.

Pathogenesis: How Cattle Botflies Damage Animal Health and Productivity

The pathogenesis of cattle botfly infestation (Hypodermiasis), primarily caused by Hypoderma bovis and Hypoderma lineatum, is driven by the migration and development of their larvae within the host’s body, causing tissue damage, inflammation, and potential severe complications.

Tissue Damage and Inflammatory Response in Infested Cattle

Skin Penetration: Adult female flies lay eggs on the hair of cattle, usually on the legs or lower body regions. The eggs hatch, and the first-stage larvae (L1) crawl to the base of the hair shaft and burrow into the skin. This penetration can cause a rash and local inflammation, often with a yellowish discharge. Larval secretions contain proteolytic enzymes that aid their movement through the host’s tissues and modulate the host’s immune response to promote larval survival.

Tissue Migration: The L1 larvae migrate through the host’s connective tissues and fascial planes for several months.

- H. lineatum larvae migrate to the submucosal connective tissue of the esophagus.

- H. bovis larvae migrate toward the spinal canal, where they accumulate in the epidural fat.

- During this phase, clinical signs of parasitism are usually not evident, but the migration itself causes tissue dissolution, fat necrosis, and inflammation along the pathways.

Warble Formation: In early winter, the late L1 larvae move from their resting sites to the subcutaneous tissue of the host’s back. They cut a breathing hole (punctum) through the skin and develop into second and third-stage larvae within a fibrous cyst, known as a warble. The warble is a granulomatous reaction formed by the host’s immune response around the parasite.

Emergence and Pupation: After 4 to 8 weeks in the warble, the mature third-stage larvae emerge through the breathing hole, drop to the ground, and pupate in the soil to complete the life cycle.

Economic Losses from Hide Damage and Meat Quality Reduction

Third-stage larvae create the most visible damage. Each warble hole permanently damages hide quality, reducing leather value. Heavy infestations with 50-100 warbles can make hides nearly worthless for premium leather production.

The meat industry also suffers losses. Tissue around warbles becomes gelatinous and blood-stained, requiring trimming during processing. This “butcher’s jelly” can affect several pounds of meat per carcass, reducing both yield and quality grades.

Clinical Signs of Cattle Botfly Infestation: Early Detection Saves Money

Recognizing Behavioral Changes During Fly Season

The first clinical signs appear during egg-laying season. Cattle exhibit extreme fear of hovering flies, running frantically with tails raised. This gadding behavior causes injuries, fence damage, and reduced grazing time. Affected herds may lose 5-10 pounds per animal during heavy fly activity.

The primary clinical signs of cattle botfly (or cattle grub/warble fly) infestation are the presence of firm, raised swellings called “warbles” on the animal’s back, and a panic response known as “gadding” to the adult flies.

Observant farmers notice cattle standing in water or seeking shade during peak fly hours. Animals may refuse to leave protective areas, reducing feed intake and milk production. Some cattle develop associative fear, showing panic responses even without flies present.

Physical Symptoms of Larval Migration and Warble Development

During migration phases, clinical signs remain subtle. Some animals show intermittent lameness, difficulty swallowing, or unexplained bloat. Cattle may exhibit localized swelling or pain along the back, particularly during late winter.

Warbles become visible as swellings along the back from December through May in most regions. These lumps measure 1-3 inches in diameter, with a small breathing hole at the center. Heavily infested animals may have 20-200 warbles, creating a lumpy appearance along the topline.

Pressing on warbles causes pain, making affected cattle difficult to handle. Some animals develop secondary bacterial infections at warble sites, causing fever, swelling, and abscesses. Severe cases show weight loss, rough hair coat, and poor overall condition.

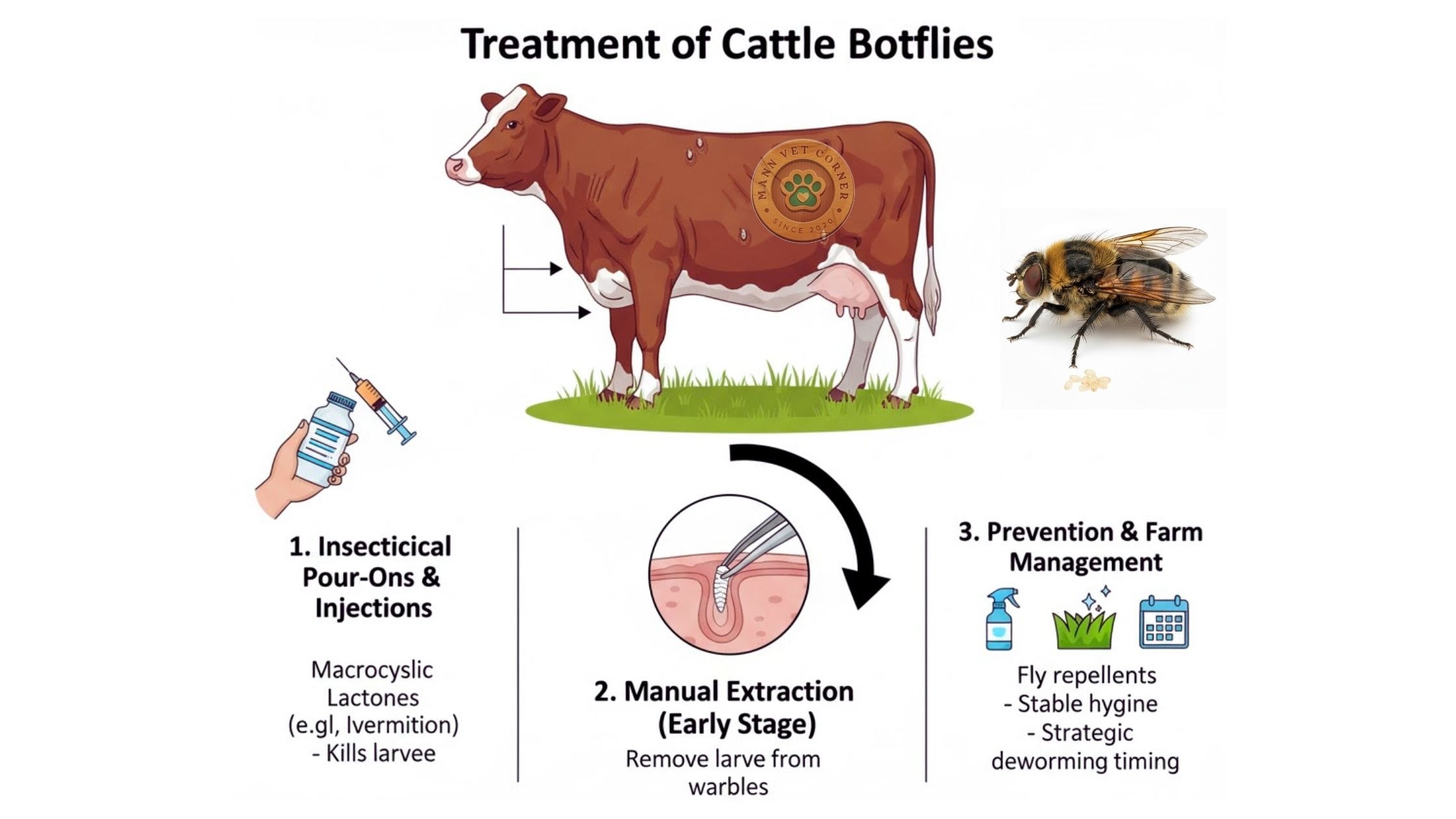

Effective Treatment Options for Cattle Botfly Control

Systemic Insecticides: Timing and Application Methods

Modern botfly treatment relies on systemic parasiticides applied at strategic times. Macrocyclic lactones (ivermectin, doramectin, eprinomectin, moxidectin) effectively kill all larval stages. These products come in injectable, pour-on, and oral formulations.

Treatment timing critically affects success and safety. The ideal treatment window occurs in fall (October-December in North America) after egg-laying ends but before larvae reach sensitive locations. Fall treatment kills first and early second-stage larvae without risk of toxic reactions.

Pour-on products offer convenience for large herds. Apply 500 mcg/kg ivermectin or equivalent doses of other avermectins along the backline. Injectable formulations provide systemic distribution, ensuring complete larval kill. Eprinomectin offers zero milk withdrawal time for dairy operations.

Treatment Precautions and Avoiding Adverse Reactions

Never treat cattle with third-stage larvae in warbles (late winter through spring) using systemic products. Killing larvae at this stage causes severe inflammatory reactions as decomposing grubs release toxins. Affected cattle may develop swelling, lameness, or paralysis.

If treatment must occur during the warble stage, manual removal offers a safer alternative. Squeeze mature warbles gently to expel larvae through breathing holes. This labor-intensive method works for small herds or individual valuable animals but proves impractical for large operations.

Always follow label withdrawal times before slaughter. Most systemic parasiticides require 35-50 day meat withdrawal periods. Read and follow all product instructions carefully to ensure food safety and treatment efficacy.

Treating Secondary Infections and Managing Complications

Warbles sometimes become infected with bacteria, requiring antibiotic treatment. Clean infected sites with antiseptic solutions and apply topical antibacterals. Severe infections may need systemic antibiotics like penicillin or oxytetracycline.

Monitor treated animals for adverse reactions, especially when treating during migration periods. Signs of trouble include sudden paralysis, severe swelling along the back, or difficulty breathing. Contact a veterinarian immediately if serious reactions occur.

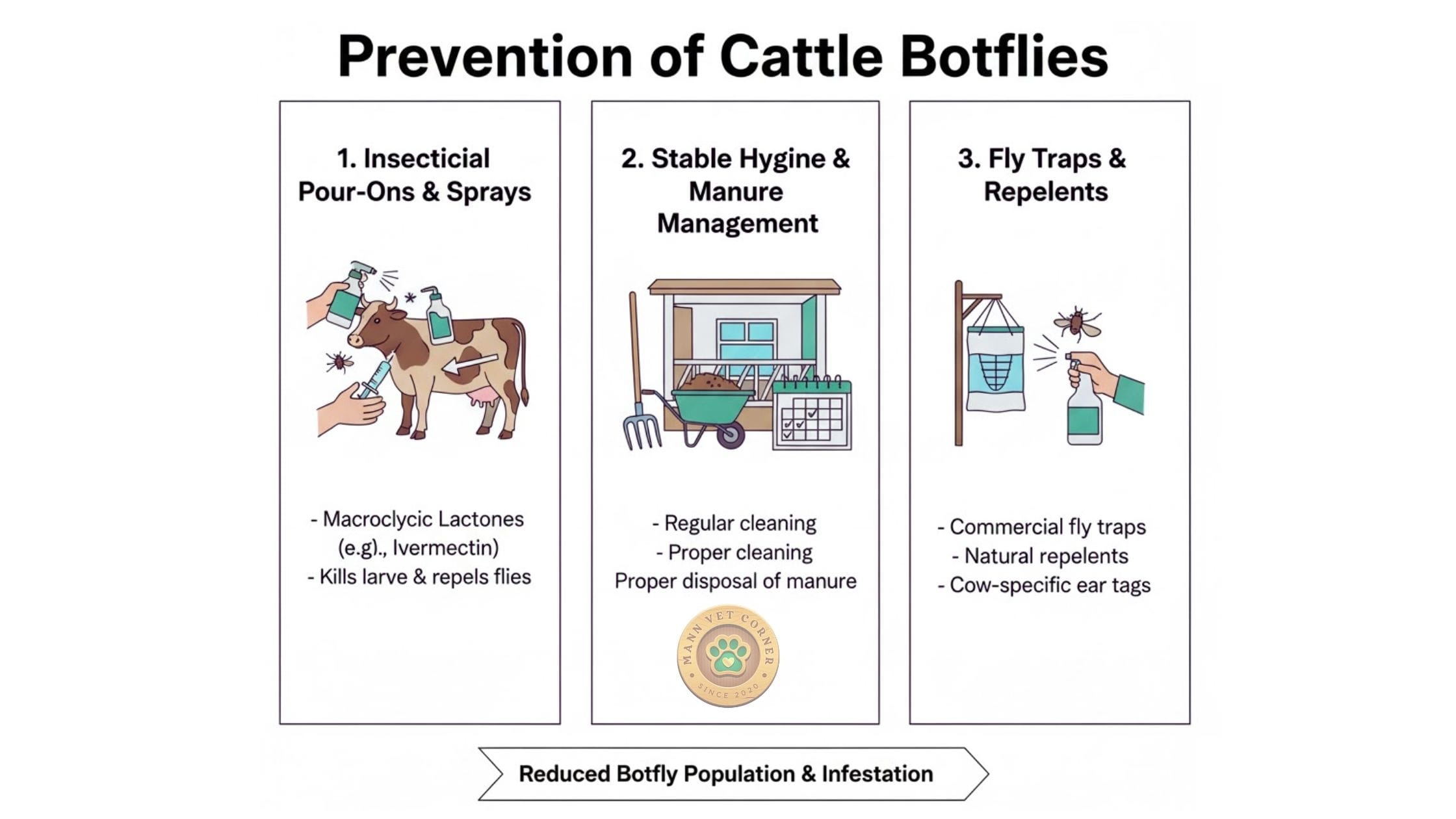

Comprehensive Prevention Strategies for Cattle Botfly Control

Strategic Treatment Programs for Year-Round Protection

Prevention programs focus on breaking the one-year life cycle through systematic fall treatments. Treating the entire herd in October or November eliminates developing larvae before they cause damage. This single annual treatment provides complete protection when properly timed.

Some programs recommend semi-annual treatments for high-risk herds. Treat once in fall to kill early larvae and again in late summer to eliminate any missed infections. This intensive approach works well for valuable breeding stock or show cattle.

Maintain detailed treatment records documenting products used, dates, and dosages. Track which animals received treatment and monitor for breakthrough infestations. Good record-keeping helps optimize timing and product selection over multiple years.

Herd Management Practices That Reduce Botfly Exposure

Reduce adult fly populations through environmental management. Remove woody debris and vegetation where flies shelter during egg-laying flights. Keep cattle away from heavily wooded areas during peak fly season when possible.

Provide shade structures or spray systems that cattle can access during fly activity hours. Animals with access to protection show less gadding behavior and maintain better production levels. Some farmers use fly-proof barns during peak season for high-value animals.

Consider grazing management strategies that separate cattle from infested areas. Rotating pastures and avoiding areas with known heavy fly populations reduces exposure. This approach works best when combined with systematic treatment programs.

Quarantine Procedures for New Animals and Disease Prevention

Quarantine all incoming cattle for 30-60 days before introducing them to your herd. Treat new arrivals with systemic parasiticides immediately upon arrival, regardless of season. This prevents introduction of botfly larvae at unexpected life stages.

Inspect purchased cattle carefully for warbles during late winter and spring. Reject animals with active warble infestations when possible, or negotiate reduced prices to account for treatment costs and hide damage. Never assume purchased animals are parasite-free.

Work with your veterinarian to develop a comprehensive parasite control program. Botflies often coexist with other parasites, requiring integrated management approaches. Regular fecal testing, strategic deworming, and proper treatment timing protect animal health and farm profitability.

Regional Considerations for Cattle Botfly Management

Geographic Distribution and Seasonal Patterns

Cattle botfly prevalence varies significantly by region. Northern climates experience concentrated fly seasons, while southern areas may have extended activity periods. High-altitude regions typically see less botfly pressure than lowland valleys.

European farmers deal primarily with Hypoderma species, while North American producers face similar challenges. Asian and African regions host different botfly species with slightly different life cycles. Understanding local species helps optimize control strategies.

Adjust treatment timing based on local climate and fly emergence patterns. Consult local veterinarians or extension agents for region-specific recommendations. What works in northern Canada may not suit producers in southern Texas.

Regulatory Status and Control Programs

Some regions have mandatory botfly control programs with legal treatment requirements. Canada and several European countries have successfully reduced or eliminated botflies through coordinated eradication efforts. Check local regulations regarding required treatments and reporting.

Where eradication programs exist, participation helps protect your herd and supports community-wide control. Report suspected botfly cases to veterinary authorities as required. Cooperation among neighboring farms proves essential for long-term success.

Monitoring Program Success and Adjusting Management Strategies

Evaluating Treatment Effectiveness Through Hide Inspection

Assess treatment program success by examining hides during processing. Work with your processor to track warble holes in carcasses. Zero or minimal warbles indicate effective control, while persistent infestations suggest program adjustments are needed.

Count warbles on live cattle during the warble season as an alternative monitoring method. Sample 10-20 percent of the herd, recording the number of warbles per animal. Average counts above five per animal suggest treatment timing or product selection problems.

Monitor cattle behavior during fly season as an indirect measure. Reduced gadding indicates lower adult fly populations resulting from successful larval control. Calm cattle that continue grazing normally during traditional fly season demonstrate effective prevention.

Long-Term Economic Benefits of Consistent Botfly Control

Calculate return on investment by comparing treatment costs against production gains. Well-designed programs typically return $3-5 for every dollar spent on prevention. Benefits include improved weight gain, better hide values, and reduced veterinary costs.

Track improvements in multiple performance metrics. Monitor average daily gain, feed conversion ratios, and milk production in dairy herds. Document hide quality improvements at processing and any premium payments received for clean hides.

Consider long-term sustainability benefits of botfly control. Healthier cattle require fewer interventions, reducing antibiotic use and veterinary visits. Animals experience less stress and pain, improving welfare outcomes that increasingly matter to consumers and regulators.

Frequently Asked Questions About Cattle Botfly Management

How do I know if my cattle have botflies? Look for lumps along the back during winter and spring months. Watch for extreme fear of flies during summer, causing cattle to run frantically. Check processed hides for characteristic holes indicating previous warble infestations.

When should I treat cattle for botflies? Treat in fall (October-December in most areas) after fly season ends but before larvae reach sensitive locations. Never treat cattle with visible warbles on their backs using systemic products without veterinary guidance.

Can botflies infect humans? While rare, botfly larvae occasionally infest humans who handle cattle or work in infested areas. Human cases require medical attention but remain uncommon with proper hygiene and protective measures.

Do botflies transmit diseases? Botflies do not transmit infectious diseases but cause significant production losses and tissue damage. The wounds they create can become secondarily infected with bacteria, requiring additional treatment.

How long do botfly treatments protect cattle? Single fall treatments provide protection for the entire year by eliminating developing larvae before they cause damage. Annual treatments maintain protection when timed correctly according to local fly emergence patterns.

Taking Action: Implementing Your Botfly Control Program Today

Cattle botflies continue threatening livestock productivity despite available control measures. Successful management requires understanding the complete life cycle, recognizing clinical signs early, and implementing strategic prevention programs. The economic benefits of proper control far exceed treatment costs.

Start by assessing your current situation. Inspect your herd for signs of infestation and review your treatment history. Consult your veterinarian to develop a comprehensive control program suited to your operation and local conditions.

Mark your calendar for fall treatments and commit to annual prevention. Train your staff to recognize botfly activity and symptoms requiring attention. With consistent management, you can eliminate botfly losses and maximize your herd’s productivity and profitability.

Remember that neighboring herds affect your success. Encourage area producers to participate in control programs for community-wide benefits. Together, farmers can reduce botfly populations and protect the livestock industry’s economic health for generations to come.