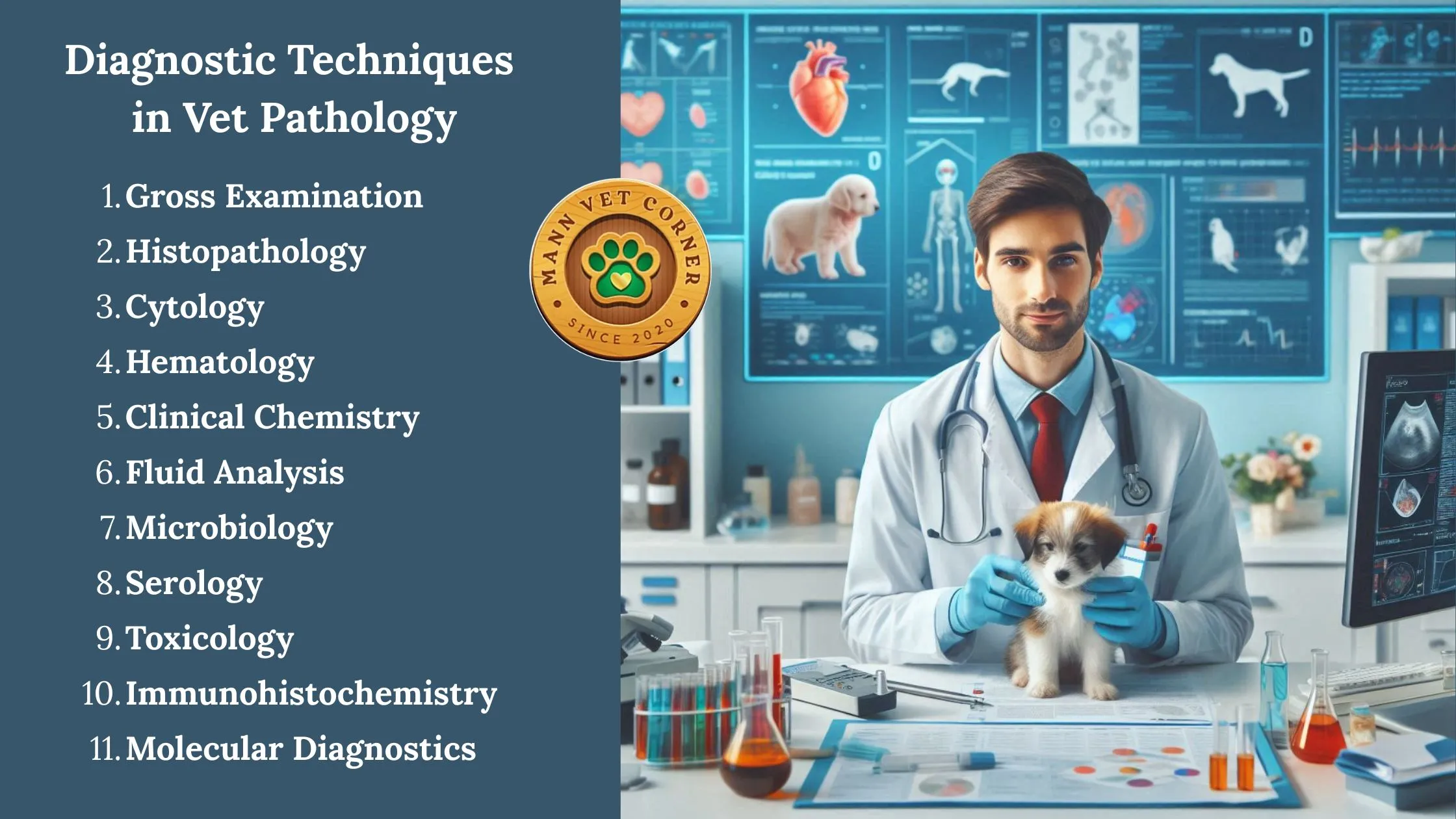

Veterinary pathology is the study of diseases in animals, encompassing both anatomic pathology (examining tissues and organs) and clinical pathology (analyzing bodily fluids and cells). Diagnostic techniques are essential for identifying disease causes, guiding treatments, monitoring health, and preventing outbreaks in companion animals, livestock, wildlife, and exotic species.

These methods integrate traditional observations with advanced technologies like molecular analysis for precise, timely diagnoses. Below, I enlist the key techniques, elaborating on each with an introduction (defining the method), purpose (its objectives), use in veterinary pathology (general applications), and extended examples (specific cases involving animals and pathologies, drawn from veterinary practices and case studies).

Gross Examination (Necropsy)

Introduction: This involves a macroscopic inspection of an animal’s body, organs, and tissues during a postmortem examination (necropsy) or biopsy, noting visible changes like lesions, discolorations, enlargements, or abnormalities without magnification.

Purpose: To provide an initial overview of pathological changes, identify potential causes of illness or death, and select samples for further testing, forming the basis for comprehensive diagnostics.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Employed in forensic investigations, disease surveillance, and routine health assessments; it helps detect trauma, infections, neoplasms, or congenital defects across species, often in labs or field settings.

Examples: In cattle, necropsy reveals spongy brain tissue indicative of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or mad cow disease), guiding prion disease confirmation and herd quarantine. In wild birds like eagles, gross examination during necropsy identifies lead poisoning from ingested fragments, showing green-stained gizzards and emaciation, supporting toxicology follow-up for wildlife conservation.

Histopathology

Introduction: The microscopic evaluation of fixed, stained tissue sections to observe cellular and architectural changes, often using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for detail.

Purpose: To confirm or rule out diseases by identifying microscopic alterations like inflammation, necrosis, or neoplastic growth that are not visible grossly.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Critical for tumor classification, infectious agent identification, and chronic disease assessment; it complements necropsy and is standard in biopsy analysis for living animals.

Examples: In dogs with suspected lymphoma, histopathology of lymph node biopsies shows diffuse sheets of neoplastic lymphocytes, confirming multicentric lymphoma and informing chemotherapy protocols. In horses with colic, examination of intestinal tissue reveals eosinophilic infiltration consistent with parasitic enteritis (e.g., from Strongylus spp.), leading to deworming strategies.

Cytology

Introduction: The study of individual cells aspirated from fluids, masses, or lesions via fine-needle aspiration, smeared on slides, stained, and examined microscopically for morphology and abnormalities.

Purpose: To offer quick, minimally invasive insights into cellular pathology, such as malignancy or infection, often as a triage before more invasive procedures.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Applied in rapid diagnostics for tumors, effusions, or inflammatory conditions; it’s cost-effective and useful in clinics for immediate decision-making.

Examples: In cats with pleural effusion, cytology of thoracic fluid reveals septic exudate with bacteria and neutrophils, diagnosing pyothorax secondary to bite wounds and prompting antibiotic therapy. In rabbits, fine-needle aspirates from cutaneous masses show spindle cells indicative of fibrosarcoma, guiding surgical excision.

Hematology

Introduction: Analysis of blood components, including complete blood counts (CBC) for red cells, white cells, and platelets, using automated analyzers or manual smears to assess counts, morphology, and indices.

Purpose: To detect hematologic disorders, infections, or systemic issues by evaluating blood cell production, function, and destruction.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Monitors anemia, leukemias, or inflammatory responses; essential in routine wellness checks and acute illness evaluations for various species.

Examples: In dogs with lethargy, hematology shows regenerative anemia and thrombocytopenia consistent with immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA), often triggered by vaccines, leading to immunosuppressive treatment. In poultry like chickens, low red cell counts indicate anemia from coccidiosis (Eimeria infection), supporting flock management with anticoccidials.

Clinical Chemistry

Introduction: Biochemical analysis of serum or plasma for enzymes, proteins, electrolytes, and metabolites using spectrophotometry or immunoassays to assess organ function.

Purpose: To evaluate metabolic, endocrine, and organ-specific health by quantifying biomarkers, aiding in differential diagnosis of systemic diseases.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Detects liver, kidney, or pancreatic dysfunction; panels are tailored to species and integrated with other tests for holistic assessments.

Examples: In older cats, elevated thyroid hormones (T4) and ALP indicate hyperthyroidism, causing weight loss and polyuria, treated with methimazole or radioiodine. In horses with muscle tying-up, high CK and AST levels confirm rhabdomyolysis, often exercise-induced, managed with rest and electrolytes.

Fluid Analysis

Introduction: Examination of non-blood fluids (e.g., urine, synovial, peritoneal, or cerebrospinal) for cellularity, proteins, and chemistry via centrifugation, cytology, and biochemistry.

Purpose: To characterize effusions, infections, or organ-specific issues by analyzing fluid composition and cells.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Diagnoses urinary, joint, or abdominal disorders; useful in emergencies for guiding fluid therapy or surgery.

Examples: In dogs with abdominal distension, peritoneal fluid analysis shows transudate with low protein, indicating portal hypertension from liver cirrhosis, requiring diuretics. In cattle, urinalysis reveals crystals and bacteria in cases of urolithiasis, leading to dietary changes to prevent urinary obstruction.

Microbiology

Introduction: Isolation and identification of pathogens (bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites) through culture, staining, or biochemical tests from samples like swabs or tissues.

Purpose: To pinpoint infectious agents and test antimicrobial susceptibility, enabling targeted therapies.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Essential for outbreak control and antibiotic stewardship; includes aerobic/anaerobic cultures and sensitivity panels.

Examples: In pigs with diarrhea, fecal cultures grow Salmonella spp., confirming salmonellosis and prompting biosecurity measures. In wild birds like parrots, tracheal swabs culture Aspergillus fumigatus, diagnosing aspergillosis treated with antifungals.

Serology

Introduction: Detection of antibodies or antigens in serum using assays like ELISA or agglutination to indicate exposure or active infection.

Purpose: To assess immune status, differentiate vaccination from infection, and screen for pathogens without direct isolation.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Monitors herd immunity and diagnoses chronic infections; paired samples track rising titers.

Examples: In dogs, ELISA detects heartworm antigens, confirming Dirofilaria immitis infection and initiating adulticide treatment. In sheep, serology shows antibodies to Brucella ovis, indicating epididymitis and requiring culling for flock health.

Toxicology

Introduction: Screening for toxins in blood, urine, or tissues via chromatography or mass spectrometry to quantify exposure levels.

Purpose: To confirm poisoning, assess severity, and evaluate organ impact for prognostic and legal purposes.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Investigates accidental ingestions or environmental exposures; includes heavy metals, pesticides, or rodenticides.

Examples: In cats ingesting lilies, elevated creatinine and urea indicate acute kidney injury from lily toxicity, treated with fluids and dialysis. In grazing cattle, liver biopsies show copper accumulation from contaminated feed, diagnosing chronic copper poisoning managed by chelation.

Immunohistochemistry

Introduction: Antibody-based staining of tissue sections to localize specific antigens, visualized microscopically for pathogen or protein detection.

Purpose: To enhance histopathology by identifying infectious agents, tumor markers, or immune cells for refined diagnosis.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Differentiates disease subtypes; vital in oncology and virology for prognosis and therapy selection.

Examples: In ferrets with Aleutian disease, IHC detects parvovirus antigens in lymphoid tissues, confirming infection and explaining chronic wasting. In goats with caprine arthritis-encephalitis, brain sections stain positive for lentivirus, diagnosing neurologic symptoms.

Molecular Diagnostics

Introduction: Genetic analysis using PCR, sequencing, or hybridization to detect pathogen DNA/RNA or host mutations.

Purpose: To provide high-sensitivity detection of elusive pathogens, strains, or genetic disorders for early intervention.

Use in Veterinary Pathology: Tracks epidemics and screens breeds; includes real-time PCR for rapid results in field or lab settings.

Examples: In poultry flocks, real-time PCR identifies avian influenza virus in swabs, enabling culling to prevent spread. In dogs with hereditary diseases, sequencing detects MDR1 gene mutations causing ivermectin toxicity in collies, informing safe parasite control.

Conclusion

Veterinary pathology employs a diverse array of diagnostic techniques, ranging from gross examination to advanced molecular diagnostics, to accurately identify and manage diseases in animals. These methods, including necropsy, histopathology, cytology, hematology, clinical chemistry, fluid analysis, microbiology, serology, toxicology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular diagnostics, collectively enable veterinarians to diagnose conditions, monitor health, and implement effective treatments across species like dogs, cats, cattle, horses, poultry, and wildlife.

By integrating macroscopic observations with microscopic and biochemical analyses, these techniques address a wide spectrum of pathologies, from infectious diseases and cancers to toxicities and genetic disorders. Their application ensures improved animal welfare, supports agricultural productivity, and aids in wildlife conservation, while ongoing advancements continue to enhance diagnostic precision and therapeutic outcomes.

so much superb info on here, : D.