ESR: A Key Tool in Veterinary Clinical Pathology

ESR: A Key Tool in Veterinary Clinical Pathology demands attention from veterinary students. Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) test, straightforward blood analysis, reveals inflammation in animals by measuring red blood cell settling speed in tubes. Illness prompts protein release like fibrinogen; red blood cells clump, sink faster, signaling infections, autoimmune disorders, cancer. ESR: A Key Tool in Veterinary Clinical Pathology fails to diagnose exact issues, acts like warning lights, prompts veterinarians to explore tests like blood counts, imaging. Test excels monitoring chronic conditions; arthritis in dogs, laminitis in horses checks treatment effectiveness. ESR: A Key Tool in Veterinary Clinical Pathology, cost-effective, simple, remains go-to clinic method, offers quick health insights, guides better care decisions.

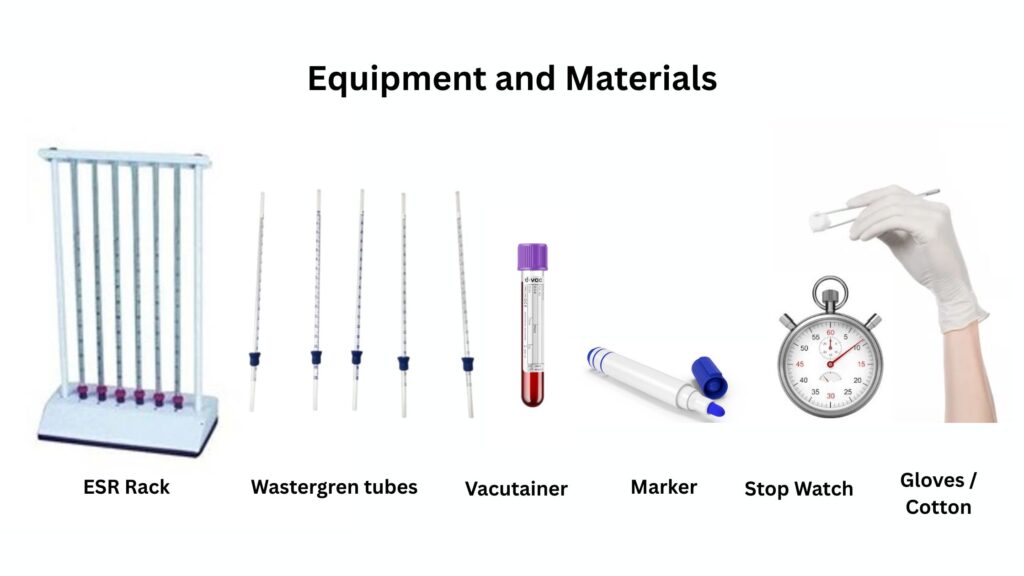

Equipment and Materials Needed for ESR Procedure

To perform an ESR test using the Westergren method, you need the following items:

- Syringe and Needle: A sterile syringe (1-2 mL) and needle to collect a blood sample from the animal’s vein.

- Anticoagulant Tube: A tube containing an anticoagulant, like EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), to prevent the blood from clotting. Typically, a purple-top tube is used.

- Westergren Tube: A tall, thin, graduated glass or plastic tube (200 mm long, 2.5 mm diameter) designed for the ESR test. This is the standard tube for measuring sedimentation.

- Westergren Rack: A stand to hold the Westergren tube vertically during the test, ensuring accurate settling of red blood cells.

- Timer or Stopwatch: To measure exactly one hour for the sedimentation process.

- Cleaning and labeling material: Alcohol swabs, cotton balls, and gloves for sterile blood collection and to maintain hygiene, and markers to identify the sample with the animal’s details.

Procedure for Performing an ESR Test

The ESR test is straightforward and doesn’t require fancy equipment. Here’s how it’s done:

Collect Blood: A vet draws a small amount of blood (usually 1-2 mL) from the animal’s vein, often using a needle and syringe. The blood is mixed with an anticoagulant, like EDTA, to prevent clotting.

Prepare the Tube: The blood is placed in a tall, thin tube called a Westergren tube (the gold standard) or a similar tube. The tube is filled to a specific mark, usually 200 mm.

Set Up the Test: The tube is placed vertically in a rack at room temperature, away from vibrations or direct sunlight, which can affect results.

Measure Sedimentation: After exactly one hour, the vet measures how far the red blood cells have settled in the tube. The distance is recorded in millimeters per hour (mm/hr).

Record Results: The result is the ESR value, which is compared to normal ranges for the animal species. Automated machines can also perform this test faster in modern labs, reducing human error.

Stages of ESR

- There are 3 stages of ESR

- Initial lag phase (10 mint) This stage of rouleaux formation sedimentation is slow.

- Phase of rapid RBC falling (40 mint) rouleaux formation increases, and the settling rate is constant.

- Packing phase (10 mint) The settling rate increases for the remainder of an hour.

Mechanism Behind ESR

ESR works because of how red blood cells behave in the blood. Normally, red blood cells float separately in plasma and settle slowly. When an animal has inflammation, the body produces proteins like fibrinogen and immunoglobulins. These proteins make red blood cells stick together, forming clumps called “rouleaux.” These clumps are heavier, so they sink faster in the tube. The faster they settle, the higher the ESR value, signaling inflammation. Other factors, like the number or shape of red blood cells, can also affect how quickly they fall. For example, too many red blood cells (polycythemia) can slow down sedimentation, while anemia can speed it up. It’s like watching sand settle in water—the heavier the clumps, the quicker they sink!

Normal and Abnormal ESR Values in Domestic, Lab, and Pet Animals

ESR values vary by species, age, and sometimes gender. Since animals like dogs, cats, horses, and lab animals (e.g., rabbits, rats) have different blood compositions, their normal ranges differ. Below is a table summarizing normal and abnormal ESR values for common domestic, lab, and pet animals:

Reasons for Increased and Decreased ESR

ESR can go up or down depending on the animal’s health. The table below lists the main reasons for changes in ESR, making it easy to understand what might be happening in a patient.

Why This Matters

As future veterinarians, understanding ESR helps you spot inflammation early and monitor how well treatments work. ESR is a prognostic test, and it detects the presence and severity of disease. It’s not a perfect test; it doesn’t tell you the exact disease, but it’s like a warning light on a car dashboard, telling you to check under the hood. By combining ESR with other tests, like C-reactive protein (CRP) or a complete blood count, you can better diagnose and treat sick animals.

shafisoomro222@gmail.com