The PPR (Peste des Petits Ruminants ), often called goat plague, is a serious viral disease that affects sheep and goats. PPR spreads quickly and can cause many deaths, making it a big problem for farmers and the economy in many parts of the world. In this blog, we’ll explore what causes, susceptible hosts, clinical signs and symptoms, the incubation period of PPR (Peste des Petits Ruminants), the pathogenesis and necropsy findings of PPR, how it shows up, and what can be done to treat it. Let’s dive in!

Etiology

PPR is caused by the Peste des Petits Ruminants virus, or PPRV for short. This virus belongs to a group called morbilliviruses, which also includes the viruses that cause measles in humans and rinderpest in cattle. PPRV is a tiny germ made of RNA, and it’s specially designed to infect small ruminants like sheep and goats. While it’s related to other viruses, it has its own unique traits that make it a serious threat to these animals.

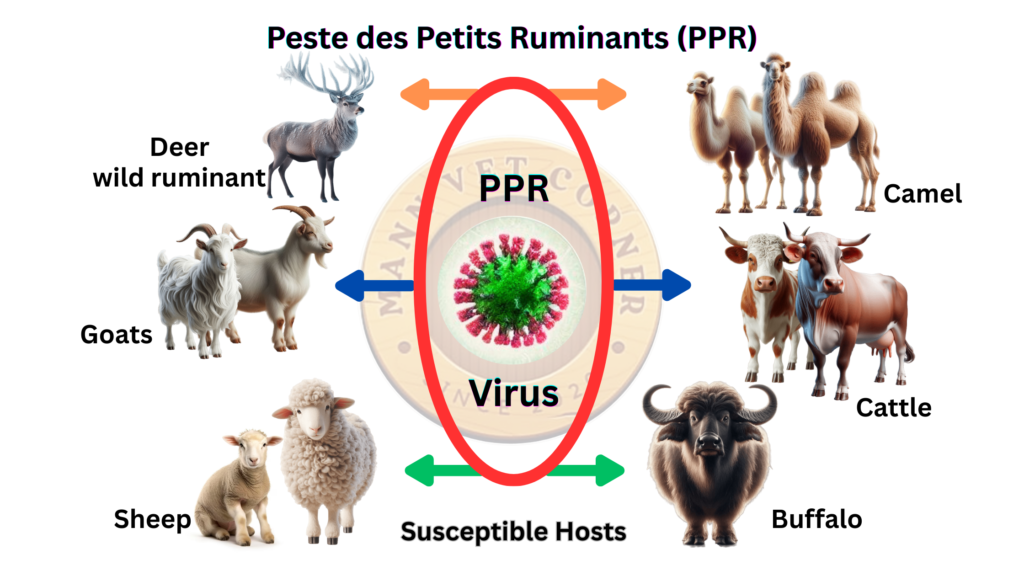

Host Susceptibility

The animals most at risk from PPR are domestic sheep and goats. These are the main targets, and the disease can spread like wildfire among them, leading to big losses for farmers. But it doesn’t stop there—wild animals like gazelles, ibex, and some types of deer can also catch PPRV, though the effects might not be as severe. Interestingly, scientists have found that cattle and pigs can get infected in lab tests, but they don’t get sick or spread the disease naturally. So, PPR is really a problem for small ruminants, especially sheep and goats.

Incubation Period

After an animal catches PPRV, it takes some time before the signs of sickness show up. This waiting time is called the incubation period. For PPR, it usually lasts between 4 and 6 days. However, it can be as short as 3 days or as long as 10 days, depending on things like how strong the virus is or how healthy the animal was to begin with. This period is when the virus is quietly multiplying inside the animal before it causes trouble.

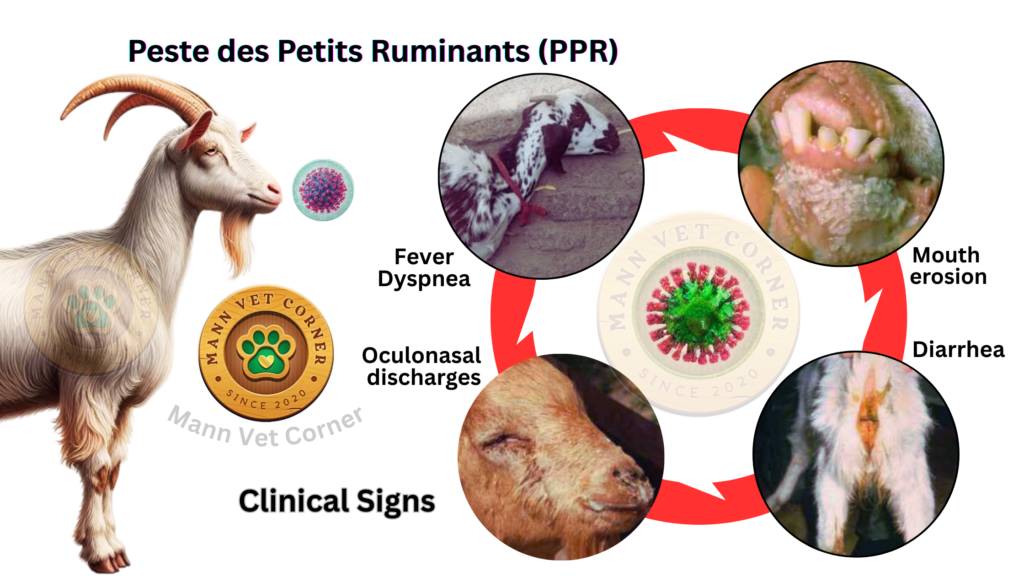

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

When PPR hits, the signs come in stages and can be pretty rough. Here’s what to look out for:

- Fever: It starts with a high fever, often between 104-106°F (40-41°C). The animal looks tired and stops eating.

- Discharges: Soon, you’ll see watery stuff coming from the eyes and nose. Later, it turns thick and pus-like.

- Mouth Sores: Painful sores pop up inside the mouth—on the tongue, gums, and roof. This makes eating hard, and the animal might drool a lot.

- Diarrhea: Many animals get bad diarrhea, sometimes with blood or mucus in it.

- Breathing Issues: In the later stages, they might cough, sneeze, or struggle to breathe.

Goats tend to get sicker than sheep, and young ones, like lambs and kids, are hit hardest. In the worst cases, animals can die within 10 to 12 days of getting sick.

Morbidity and Mortality

PPR spreads fast, and in a group of animals that haven’t been exposed before, almost all of them can get sick—that’s a morbidity rate of up to 100%. The death rate is also high, ranging from 50% to 90%. How many die depends on things like how nasty the virus strain is, whether the animals are sheep or goats, and if other infections join in. In places where PPR is new, it can wipe out huge numbers of animals.

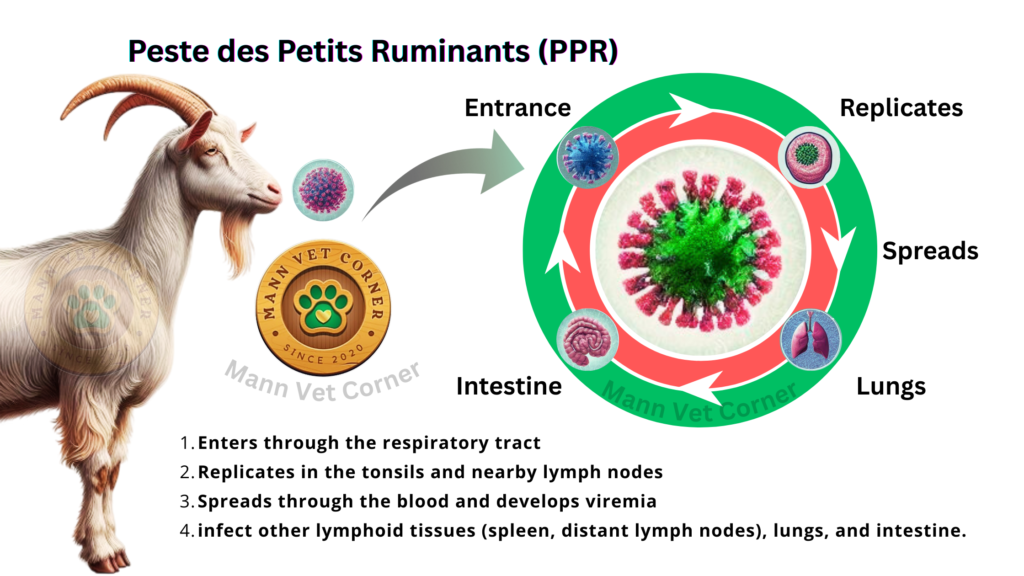

Pathogenesis

The process of how PPR develops in goats is as follows:

- Entry: The virus enters through the respiratory tract (nose or mouth) via inhaled droplets or contact with contaminated surfaces.

- Initial Replication: PPRV targets tonsils and regional lymph nodes, infecting lymphoid cells and multiplying rapidly.

- Viremia: The virus enters the bloodstream, spreading to the spleen, other lymph nodes, and epithelial tissues in the lungs and gut.

- Damage:

- Immunosuppression: PPRV infects and destroys lymphocytes (white blood cells), weakening the immune system.

- Tissue Destruction: It damages epithelial linings, causing mouth ulcers, gut inflammation (leading to diarrhea), and lung damage (causing pneumonia).

- Secondary Infections: The weakened immune system allows bacteria to cause additional infections, worsening symptoms like diarrhea and respiratory issues.

- Outcome: This multi-system attack leads to severe illness, with rapid progression in goats due to their high susceptibility.

Postmortem Findings

In goats that die from PPR, veterinarians observe distinct signs during necropsy:

- Mouth Lesions: Ulcers and erosions on the tongue, gums, palate, and inner cheeks, sometimes with a cheesy coating.

- Gastrointestinal Tract:

- Inflammation and hemorrhages in the stomach and intestines.

- Zebra striping: Dark, striped patterns in the large intestine due to congestion and bleeding.

- Lymphoid Tissues: Swollen lymph nodes (e.g., mesenteric or bronchial), sometimes with hemorrhages.

- Respiratory System: Pneumonia with consolidated, discolored lung patches and frothy fluid in airways.

- General Signs: Dehydration and emaciation from severe diarrhea and reduced eating.

- These clues help confirm that PPR was the cause of death.

Treatment

Sadly, there’s no magic pill to cure PPR because it’s a virus. Instead, the focus is on helping the animal feel better and fight off extra infections. Here’s what can be done:

- Fluid Therapy: Rehydrate with oral or intravenous fluids to counter diarrhea and fever losses.

- Nutrition: Provide soft, palatable feed to encourage eating despite mouth sores.

- Antibiotics: Administer drugs like oxytetracycline to control secondary bacterial infections (e.g., pneumonia).

- Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Reduce fever and pain to improve comfort.

Management: Keep sick goats in a clean, quiet, and warm environment to reduce stress.

Outcome: Despite treatment, many goats, especially young ones, may die due to the disease’s severity.

Prevention is Key: Vaccination with live-attenuated PPR vaccines (e.g., Nigeria 75/1 strain) is the most effective way to protect goats, as treatment alone is often insufficient.

Conclusion

Peste des Petits Ruminants is a tough disease that hits sheep and goats hard, causing suffering and economic loss. By knowing what causes it, spotting the signs early, and giving good care, we can help some animals pull through. Still, prevention—like vaccinating herds and keeping farms clean—is the real key to stopping PPR in its tracks. Understanding this disease is the first step to fighting it!

thank you for sharing with us, I conceive this website really stands out : D.

I used to be very pleased to find this internet-site.I wished to thanks to your time for this glorious learn!! I definitely enjoying each little bit of it and I’ve you bookmarked to check out new stuff you weblog post.