Introduction to Domestic Animal Skeletal Systems

The skeletal framework of domestic animals represents one of nature’s most fascinating examples of evolutionary adaptation and functional design. Understanding the comparative anatomy of animal skeletons provides crucial insights for veterinary professionals, animal scientists, biologists, and anyone working closely with domestic species. This comprehensive analysis explores the skeletal structures of common domestic animals, highlighting their similarities, differences, and functional adaptations.

From the agile dog to the powerful horse, each species has evolved unique skeletal characteristics that reflect their ecological niche, locomotor patterns, and behavioral adaptations. The study of comparative osteology reveals how similar basic building blocks can be modified to serve vastly different functions across species.

What is an Animal Skeleton?

Definition and Basic Structure

An animal skeleton is the rigid framework that provides structural support, protection for vital organs, and attachment points for muscles, enabling movement and locomotion. The skeleton serves as the body’s architectural foundation, determining an animal’s shape, size, and physical capabilities.

Composed primarily of bone tissue (osseous tissue) and cartilage, the skeletal system represents a living, dynamic organ system that continuously remodels throughout an animal’s lifetime. Bone tissue consists of specialized cells (osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts) embedded in a mineralized extracellular matrix rich in calcium phosphate and collagen fibers.

Functions of the Skeletal System

The skeletal system performs multiple critical functions:

Structural support: Maintains body shape and posture, providing a framework against which soft tissues are organized

Protection: Shields vital organs from injury—the skull protects the brain, the rib cage safeguards the heart and lungs, and the vertebrae encase the spinal cord

Movement facilitation: Provides leverage points for muscle attachment, creating a system of levers that enables locomotion and precise movements

Mineral storage: Stores calcium and phosphorus, serving as a reservoir for these essential minerals that can be mobilized when needed

Blood cell production: Houses bone marrow for hematopoiesis, producing red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

Metabolic regulation: Participates in mineral homeostasis, regulating calcium and phosphate levels in the bloodstream through hormonal control

Types of Skeletal Systems in Animals

Endoskeleton vs. Exoskeleton

Domestic animals possess endoskeletons—internal skeletal structures composed primarily of bone and cartilage. This contrasts with exoskeletons found in arthropods like insects and crustaceans. The endoskeletal system allows for greater size potential, more efficient growth patterns, superior protection of internal organs, and enhanced flexibility for diverse movement patterns.

The endoskeleton grows with the animal, eliminating the need for molting and allowing continuous size increase throughout development. This characteristic has enabled mammals to achieve larger body sizes compared to arthropods.

Axial and Appendicular Skeleton

The mammalian skeleton divides into two main functional components:

Axial skeleton: Includes the skull, vertebral column, ribs, and sternum—forming the body’s central axis and protecting vital organs

Appendicular skeleton: Comprises the limbs and their girdles (pectoral and pelvic), specialized for locomotion and manipulation

Comparative Analysis of Domestic Animal Skeletons

Dog Skeleton (Canis familiaris)

Skull and Dental Structure

Dogs possess a distinctive skull morphology with significant breed variation ranging from the elongated skull of the Greyhound (dolichocephalic) to the shortened skull of the Bulldog (brachycephalic). The canine skull features a prominent sagittal crest for muscle attachment, large temporal fossae accommodating powerful jaw muscles, and sophisticated jaw mechanics adapted for carnivorous feeding.

Dental formula: 3/3 incisors, 1/1 canines, 4/4 premolars, 2/3 molars, totaling 42 teeth in adults. The carnassial teeth (upper fourth premolar and lower first molar) are specially adapted for shearing meat.

Vertebral Column

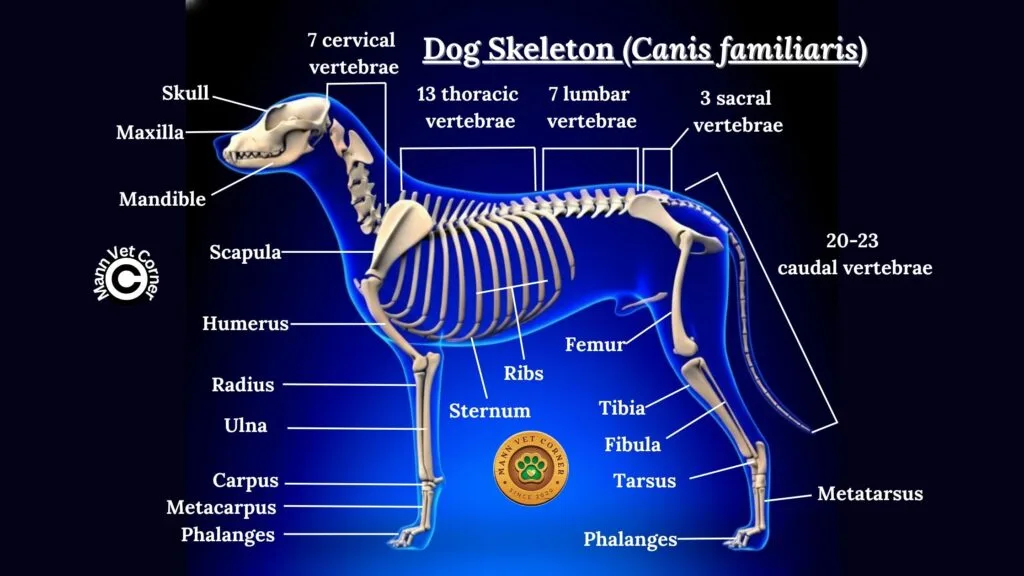

The dog’s vertebral column consists of:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Provide neck flexibility and head movement

- 13 thoracic vertebrae: Each articulates with a pair of ribs

- 7 lumbar vertebrae: Large, robust vertebrae supporting abdominal weight

- 3 sacral vertebrae: Fused to form the sacrum, articulating with the pelvis

- 20-23 caudal vertebrae: Form the tail, with significant breed variation

Limb Structure

Dogs are digitigrade animals, walking on their toes with the metacarpals and metatarsals elevated. This adaptation provides greater speed and agility by effectively lengthening the limb. The forelimbs bear approximately 60% of body weight, while hindlimbs provide propulsive force for acceleration and jumping.

The scapula is not attached to the axial skeleton by bone but rather by muscular attachments, allowing greater range of motion. The pelvic limb features a prominent greater trochanter on the femur and a well-developed calcaneal tuber (heel) for powerful muscle attachments.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The pectoral girdle consists of the scapula and clavicle (vestigial or absent in dogs), while the pelvic girdle comprises the ilium, ischium, and pubis fused to form the os coxae. The pelvis articulates with the sacrum at the sacroiliac joint.

Cat Skeleton (Felis catus)

Skull and Dental Structure

The feline skull is characterized by its shortened facial region and large orbits, providing excellent binocular vision for hunting. The temporal fossae are extensive, accommodating powerful temporalis muscles. The skull demonstrates pronounced brachycephalic features compared to wild felids, especially in certain breeds.

Dental formula: 3/3 incisors, 1/1 canines, 3/2 premolars, 1/1 molars, totaling 30 teeth. Cats have fewer teeth than dogs, reflecting their strictly carnivorous diet. The carnassial teeth are highly developed for efficient meat processing.

Vertebral Column

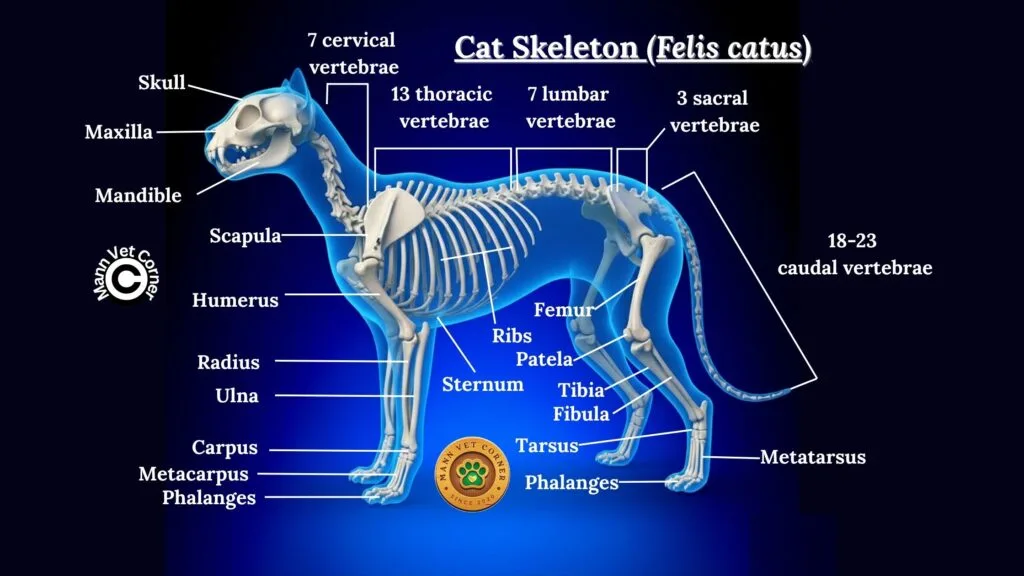

The cat’s vertebral column exhibits remarkable flexibility:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Enable the characteristic head rotation

- 13 thoracic vertebrae: Articulate with 13 pairs of ribs

- 7 lumbar vertebrae: Exceptionally flexible, allowing the distinctive arching behavior

- 3 sacral vertebrae: Fused to form a robust sacrum

- 18-23 caudal vertebrae: Form a highly mobile tail for balance

The cat’s spine is notably more flexible than the dog’s, with looser ligamentous attachments between vertebrae, enabling extreme flexion and the ability to rotate the spine nearly 180 degrees.

Limb Structure

Cats are also digitigrade but possess retractable claws, a unique adaptation requiring specialized digital anatomy. The forelimbs are extremely flexible with a floating clavicle that allows the cat to narrow its body profile when squeezing through tight spaces.

The hindlimbs are proportionally longer and more powerful than forelimbs, providing exceptional jumping ability—cats can jump up to six times their body length. The patella (kneecap) is relatively large, and the fibula is complete and well-developed.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The feline pectoral girdle features a small, vestigial clavicle embedded in muscle, allowing greater shoulder mobility. The pelvis is narrow and elongated, contributing to the cat’s agile movements and ability to land safely after falls (righting reflex).

Sheep Skeleton (Ovis aries)

Skull and Dental Structure

Sheep possess a typical ruminant skull characterized by the absence of upper incisors, which are replaced by a dental pad. The skull is elongated with a relatively small cranium compared to the facial region. Many breeds possess horn cores extending from the frontal bone.

Dental formula: 0/3 incisors, 0/1 canines, 3/3 premolars, 3/3 molars, totaling 32 teeth. The dental pad works against the lower incisors for grazing, while the molars feature high crowns (hypsodont) adapted for grinding fibrous vegetation.

Vertebral Column

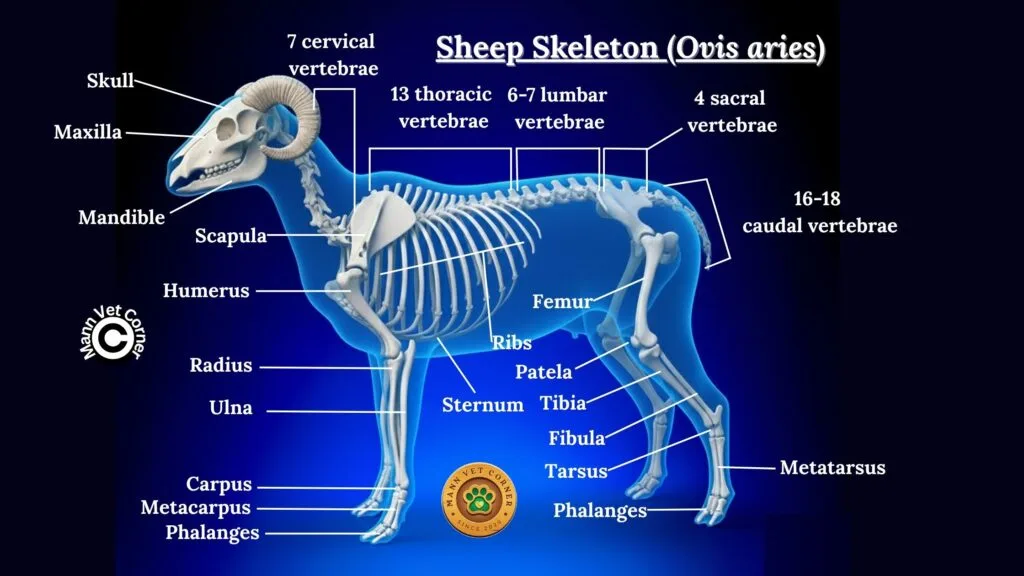

The sheep’s vertebral column structure:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Support the head during grazing

- 13 thoracic vertebrae: Form an arched thorax for optimal lung capacity

- 6-7 lumbar vertebrae: Provide flexibility and support for abdominal organs

- 4 sacral vertebrae: Fused to form a strong sacrum

- 16-18 caudal vertebrae: Form a short tail

The spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae are notably long, particularly in the anterior thoracic region, creating the characteristic withers.

Limb Structure

Sheep are unguligrade animals, walking on their hoofs (modified toenails). They possess a two-toed (didactyl) foot structure, walking on the third and fourth digits, which are enclosed in hooves. The second and fifth digits are reduced to vestigial dewclaws.

The metacarpal and metatarsal bones of the third and fourth digits are fused to form a single cannon bone, providing strength and stability. The limbs are specialized for sustained standing and efficient terrestrial locomotion rather than speed.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The pectoral girdle lacks a clavicle entirely, limiting lateral limb movement but enhancing forward-backward limb swing for efficient walking. The scapula is narrow with a prominent scapular spine. The pelvic girdle is broad and robust, adapted to support the weight of pregnancy and accommodate parturition.

Goat Skeleton (Capra hircus)

Skull and Dental Structure

The goat skull closely resembles the sheep skull but is generally lighter and more angular. The frontal bone often supports permanent horn cores in both sexes, though this varies by breed. The skull features prominent supraorbital foramina and a relatively straight facial profile.

Dental formula: Identical to sheep (0/3 incisors, 0/1 canines, 3/3 premolars, 3/3 molars, totaling 32 teeth). However, goats are browsers rather than grazers, reflected in slightly different wear patterns on their hypsodont molars.

Vertebral Column

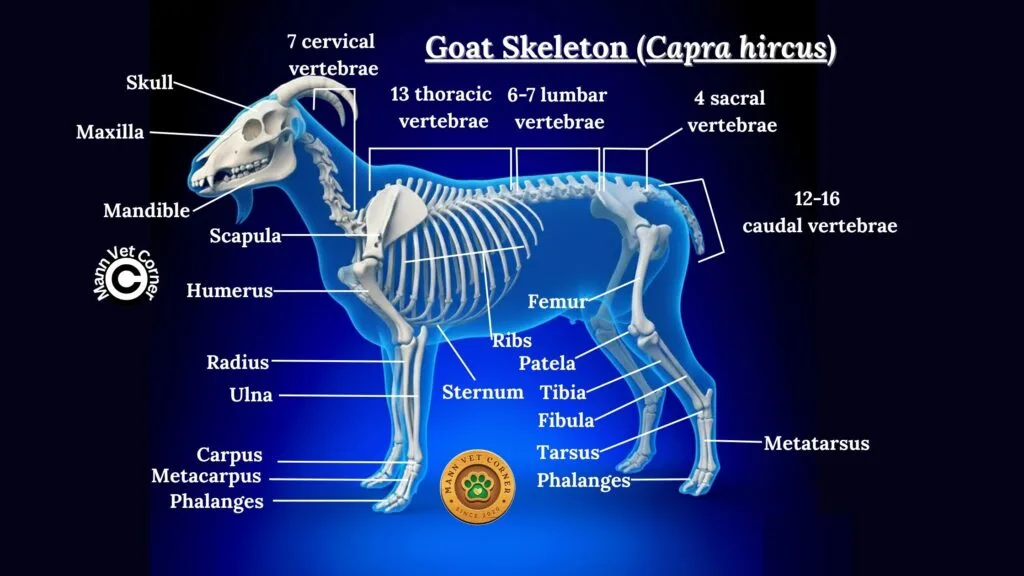

The goat’s vertebral arrangement:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Provide excellent head mobility for browsing

- 13 thoracic vertebrae: Support 13 pairs of ribs

- 6-7 lumbar vertebrae: Longer than sheep, providing greater flexibility

- 4 sacral vertebrae: Fused for pelvic stability

- 12-16 caudal vertebrae: Form a short, mobile tail

Goats demonstrate greater spinal flexibility than sheep, correlating with their climbing abilities and more diverse feeding behaviors.

Limb Structure

Like sheep, goats are unguligrade with a didactyl foot structure. However, goat limbs are proportionally longer and more slender, adapted for climbing and navigating rocky terrain. The hooves are narrower and harder than sheep hooves, with greater gripping ability.

The pastern angle is steeper in goats, and the dewclaws are positioned higher on the limb. The cannon bones are more refined, and the entire limb structure reflects adaptations for agility over power.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The goat’s pectoral girdle is narrow with an elongated scapula featuring a prominent spine. The pelvic girdle is narrower than sheep, with a more acute pelvic angle, reflecting the breed’s climbing adaptations and generally smaller offspring size.

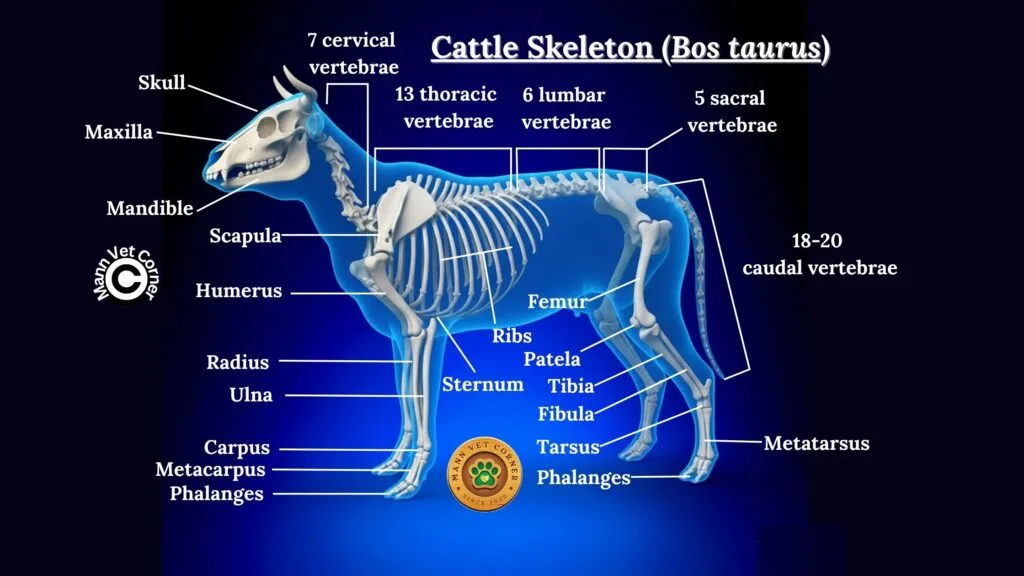

Cattle Skeleton (Bos taurus)

Skull and Dental Structure

The bovine skull is large and robust, characterized by massive frontal bones that may support permanent horn cores in both sexes. The skull features extensive frontal sinuses that lighten the overall weight. The facial region is elongated to accommodate extensive tooth rows and the nasal cavity.

Dental formula: 0/3 incisors, 0/1 canines, 3/3 premolars, 3/3 molars, totaling 32 teeth. Like other ruminants, cattle lack upper incisors and possess a dental pad. The molars are selenodont (crescent-shaped cusps) and hypsodont, ideal for grinding fibrous grasses.

Vertebral Column

The cattle vertebral structure:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Robust to support the heavy head

- 13 thoracic vertebrae: Each bearing a pair of ribs

- 6 lumbar vertebrae: Large and weight-bearing

- 5 sacral vertebrae: Fused to form a massive sacrum

- 18-20 caudal vertebrae: Form the tail (dock and switch)

The thoracic vertebrae feature exceptionally long spinous processes, particularly vertebrae 4-6, creating prominent withers essential for supporting the massive head and neck through ligamentous attachments (nuchal ligament).

Limb Structure

Cattle are unguligrade with didactyl feet, walking on the third and fourth digits. The limbs are massive and pillar-like, adapted for supporting considerable body weight. The cannon bone is thick and strong, formed by the fused third and fourth metacarpal/metatarsal bones.

The hooves are large and splayed, distributing weight over a broader surface area. The accessory digits (dewclaws) are more prominent than in sheep and goats. The pasterns are relatively short and strong, providing stability rather than shock absorption.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The bovine pectoral girdle features a massive, triangular scapula with a prominent scapular spine. The pelvic girdle is exceptionally broad and robust, adapted for bearing the weight of late pregnancy and accommodating the birth of large calves. The ilium is nearly horizontal, and the ischial tuberosities are prominent.

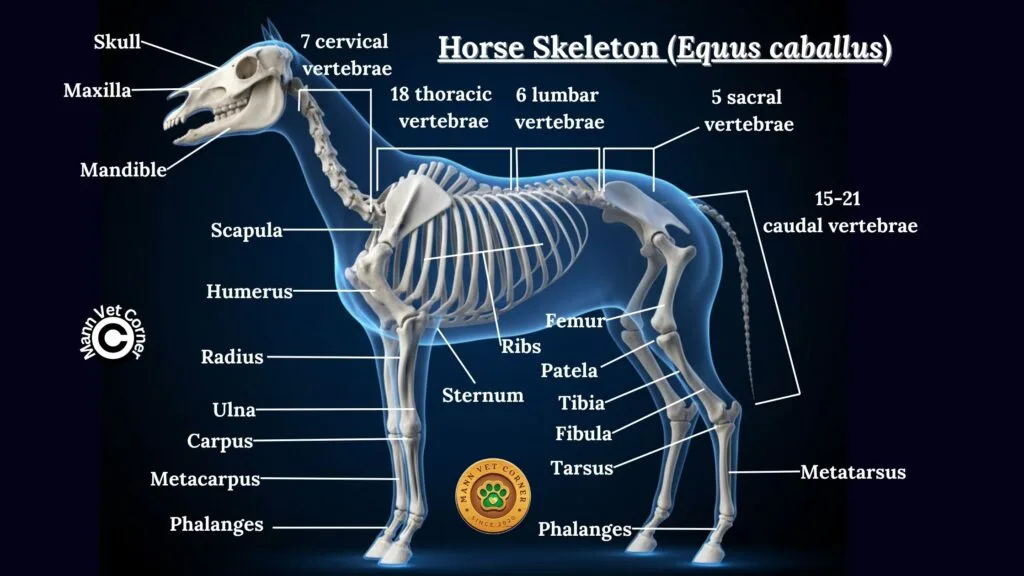

Horse Skeleton (Equus caballus)

Skull and Dental Structure

The equine skull is elongated with a lengthy facial region housing extensive dental arcades. The skull features large orbits positioned laterally for panoramic vision, and a complete post-orbital bar. The jaw is deep to accommodate high-crowned teeth.

Dental formula: 3/3 incisors, 1/1 canines (often absent or reduced in mares), 3-4/3 premolars, 3/3 molars, totaling 40-42 teeth. Horses possess a diastema (gap) between incisors and cheek teeth where the bit rests. The molars are extremely hypsodont, continuously erupting throughout much of the horse’s life.

Vertebral Column

The equine vertebral structure:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Long, allowing extensive head and neck reach

- 18 thoracic vertebrae: Each articulating with a rib (though variations exist)

- 6 lumbar vertebrae: Large, limiting spinal flexibility

- 5 sacral vertebrae: Fused into a robust sacrum

- 15-21 caudal vertebrae: Form the dock of the tail

Horses have relatively inflexible spines compared to carnivores, with limited lateral and dorsoventral flexibility. This rigidity enhances efficiency in forward locomotion and weight-carrying.

Limb Structure

Horses are unguligrade animals that have evolved to walk on a single digit (monodactyl)—the third digit. This represents an extreme adaptation for cursorial locomotion (running). The second and fourth digits are reduced to splint bones, visible as small bones adjacent to the cannon bone (third metacarpal/metatarsal).

The limbs are extremely specialized with elongated distal segments. The radius and ulna are fused in the forelimb, as are the tibia and fibula in the hindlimb. This fusion prevents rotation but provides stability at high speeds. The single hoof distributes impact forces efficiently.

The stay apparatus—a system of ligaments and tendons—allows horses to lock their limbs and sleep standing up while using minimal muscular effort. The forelimbs bear approximately 60% of body weight during standing and even more during landing from jumps.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The equine pectoral girdle features a large, triangular scapula with extensive muscle attachment sites. The complete absence of a clavicle allows for maximum forward-backward limb excursion. The pelvic girdle is powerful with prominent tuber coxae (points of hip) and tuber ischii, providing leverage for powerful hindlimb muscles that drive forward propulsion and jumping.

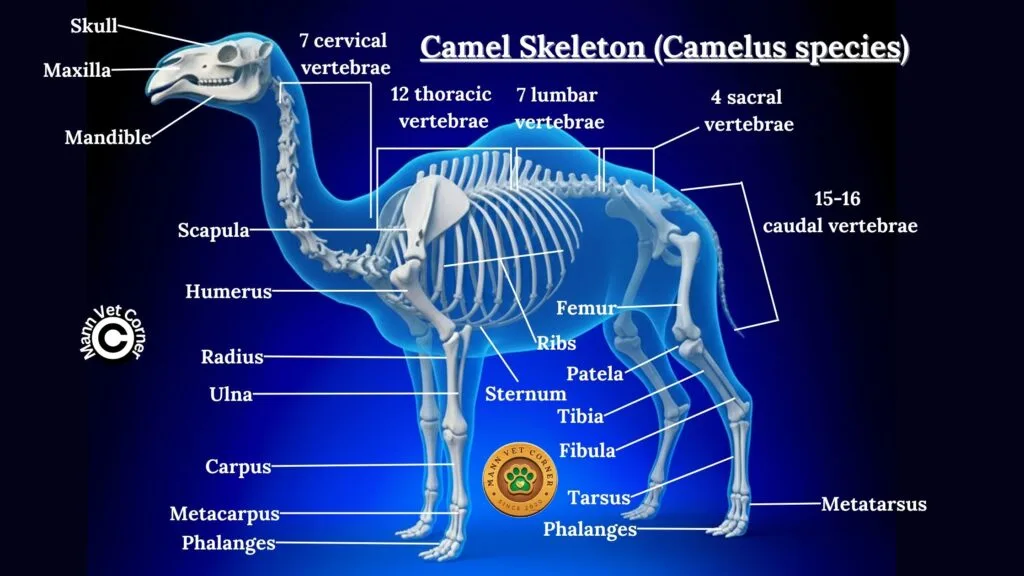

Camel Skeleton (Camelus species)

Skull and Dental Structure

The camelid skull is elongated with a convex facial profile. The skull is relatively lightweight with extensive sinuses. The orbits are large and prominent, providing excellent vision. The nasal bones are short, correlating with the muscular, mobile upper lip.

Dental formula: 1/3 incisors, 1/1 canines, 3/2 premolars, 3/3 molars, totaling 34 teeth. Unlike other ruminants, camels retain upper incisors and prominent canines. The molars are selenodont and adapted for processing coarse desert vegetation.

Vertebral Column

The camel’s vertebral structure:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Exceptionally long, providing extensive neck reach

- 12 thoracic vertebrae: Support 12 pairs of ribs

- 7 lumbar vertebrae: Long and flexible

- 4 sacral vertebrae: Fused to form the sacrum

- 15-16 caudal vertebrae: Form a medium-length tail

The most distinctive feature is the presence of thoracic vertebrae modified to support the fatty hump (or humps in Bactrian camels). These vertebrae have elongated spinous processes providing attachment for hump-supporting ligaments.

Limb Structure

Camels are unusual ungulates with several unique adaptations. While still unguligrade, camels walk on the third and fourth digits, but unlike other artiodactyls, they possess broad, soft footpads rather than hard hooves. The toes spread widely, increasing surface area for walking on sand.

The limbs are long and positioned beneath the body, adapted for desert locomotion. The cannon bones are elongated, and the limbs lack lateral dewclaws entirely. The knee (carpal) and hock (tarsal) joints have thickened skin pads (callosities) that protect against hot sand when resting.

Camels use a pacing gait (both legs on one side move together), which is energy-efficient for desert travel but provides less stability on uneven terrain.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The camel’s pectoral girdle features a long, narrow scapula adapted for the pacing gait. The pelvic girdle is narrow and elongated with prominent tuber coxae. The pelvis is adapted for the characteristic sitting position, with sternal and leg callosities bearing body weight when resting.

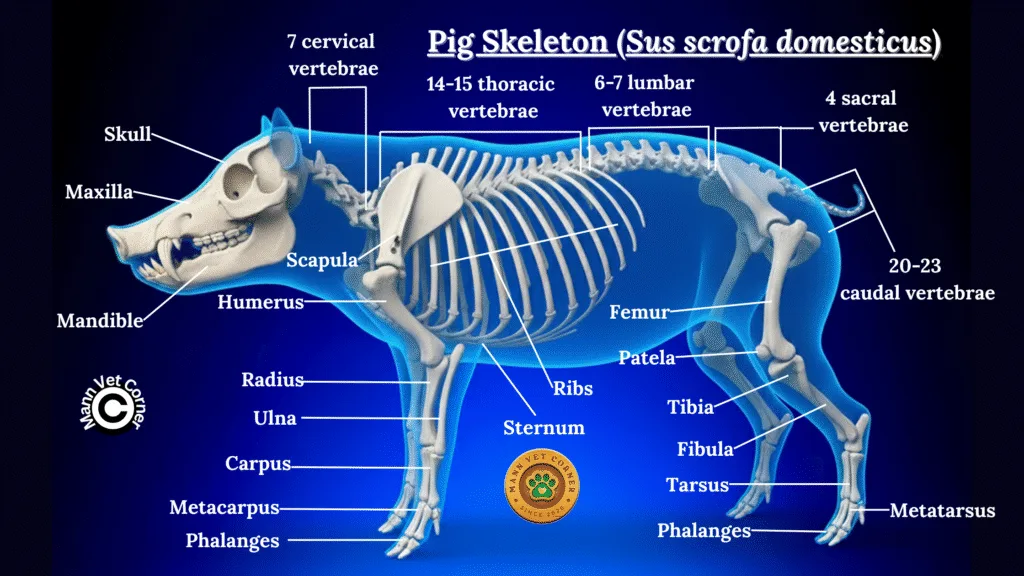

Pig Skeleton (Sus scrofa domesticus)

Skull and Dental Structure

The porcine skull is characterized by a distinctive elongated rostrum (snout) adapted for rooting behavior. The skull is triangular in lateral view with a complete zygomatic arch. The occipital region is vertical, and the skull features prominent temporal ridges but lacks a sagittal crest.

Dental formula: 3/3 incisors, 1/1 canines, 4/4 premolars, 3/3 molars, totaling 44 teeth—the most of any common domestic mammal. Pigs possess brachydont teeth (low-crowned) with distinct roots, reflecting their omnivorous diet. The canines, especially in males, may develop into tusks that grow continuously.

Vertebral Column

The pig’s vertebral structure:

- 7 cervical vertebrae: Relatively short and robust

- 14-15 thoracic vertebrae: Support 14-15 pairs of ribs

- 6-7 lumbar vertebrae: Large and weight-bearing

- 4 sacral vertebrae: Fused to form the sacrum

- 20-23 caudal vertebrae: Form a twisted tail

Pigs have more thoracic and lumbar vertebrae than most other domestic mammals, correlating with their elongated body form and ability to produce large litters. The vertebral column is relatively straight without pronounced curves.

Limb Structure

Pigs are unguligrade with a paraxonic foot structure (weight-bearing axis passing between third and fourth digits). They walk on four toes, with the third and fourth digits being primary weight-bearing digits and the second and fifth digits (lateral toes) touching the ground, particularly on soft surfaces.

Each digit terminates in a small hoof rather than a large single hoof as in horses or fused hooves as in cattle. This provides better traction on diverse terrain. The cannon bone is not fused but consists of separate third and fourth metacarpals/metatarsals.

The limbs are relatively short and stout, adapted for supporting a heavy body with a low center of gravity. This structure is not built for speed but rather for strength and stability.

Pelvic and Pectoral Girdles

The porcine pectoral girdle features a broad, fan-shaped scapula without a prominent spine. The pelvic girdle is broad and robust, adapted to accommodate large litters. The pelvis is horizontally oriented with prominent tuber coxae and a large obturator foramen.

Key Comparative Features Across Species

Skull Adaptations and Feeding Strategies

Carnivores (dogs and cats) possess shortened skulls with powerful jaw mechanics, large temporal fossae for jaw muscle attachment, and specialized carnassial teeth. Herbivores demonstrate elongated facial regions to accommodate extensive dental arcades, dental pads replacing upper incisors (except camels), and high-crowned (hypsodont) teeth for grinding vegetation. Omnivores (pigs) show intermediate features with generalized dentition.

Vertebral Column Variations

Flexibility varies dramatically: carnivores possess flexible spines for agility and hunting, ungulates have relatively rigid spines for stability and weight-bearing, and cervical length correlates with feeding strategy (browsing vs. grazing). Thoracic vertebrae numbers range from 12-18 across species, affecting body length and rib cage size.

Limb Structure and Locomotion

Three primary locomotor patterns exist among domestic mammals:

Digitigrade: Dogs and cats walk on toes, with elevated metacarpals/metatarsals providing speed and agility

Unguligrade: Hoofed animals walk on hoof tips, with extremely elongated distal limb segments maximizing stride length and efficiency

Plantigrade: (Not common in domestic species, but seen in bears) walking on entire foot including heel

Weight Distribution and Body Support

Carnivores demonstrate forelimb-heavy weight distribution (approximately 60/40 front to rear), while ungulates show more balanced distribution or slight hindlimb emphasis. Body size significantly influences skeletal robustness, with larger animals requiring proportionally thicker bones to support weight according to allometric scaling principles.

Evolutionary Adaptations

Each species demonstrates skeletal modifications reflecting their evolutionary history: cursorial adaptations in horses for sustained running, scansorial adaptations in goats for climbing, fossorial adaptations in pig snouts for rooting, and specialized carnivore features for predation in dogs and cats.

Clinical and Practical Applications

Veterinary Medicine

Understanding comparative skeletal anatomy is essential for accurate radiographic interpretation across species, species-specific orthopedic procedures, predicting breed-specific skeletal disorders, and developmental orthopedic diseases in rapidly growing animals.

Animal Husbandry

Skeletal knowledge informs proper nutrition for bone development, housing design accommodating natural postures and movements, recognition of skeletal abnormalities affecting productivity, and breeding decisions considering skeletal soundness.

Forensic Applications

Comparative osteology enables species identification from skeletal remains, age estimation using skeletal maturity markers, sex determination from pelvic structure, and individual identification through unique skeletal features.

Evolutionary Studies

Skeletal comparisons reveal phylogenetic relationships between species, adaptive radiation in response to environmental pressures, convergent evolution in similar ecological niches, and domestication effects on skeletal morphology.

Comparative Analysis Table of Domestic Animal Skeletons

Table 1: Vertebral Column Comparison

| Species | Cervical | Thoracic | Lumbar | Sacral | Caudal | Total Vertebrae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog | 7 | 13 | 7 | 3 (fused) | 20-23 | 50-53 |

| Cat | 7 | 13 | 7 | 3 (fused) | 18-23 | 48-53 |

| Sheep | 7 | 13 | 6-7 | 4 (fused) | 16-18 | 46-49 |

| Goat | 7 | 13 | 6-7 | 4 (fused) | 12-16 | 42-47 |

| Cattle | 7 | 13 | 6 | 5 (fused) | 18-20 | 49-51 |

| Horse | 7 | 18 | 6 | 5 (fused) | 15-21 | 51-57 |

| Camel | 7 | 12 | 7 | 4 (fused) | 15-16 | 45-46 |

| Pig | 7 | 14-15 | 6-7 | 4 (fused) | 20-23 | 51-56 |

Common Skeletal Disorders Across Species

Developmental Disorders

Hip dysplasia affects dogs, cats, and cattle, while osteochondrosis occurs in rapidly growing animals including dogs, horses, and pigs. Angular limb deformities impact all species during growth periods, and nutritional deficiencies cause rickets and osteomalacia across taxa.

Degenerative Conditions

Osteoarthritis affects all species, particularly in weight-bearing joints. Degenerative joint disease correlates with age and use intensity. Intervertebral disc disease primarily affects dogs, especially chondrodystrophic breeds. Osteoporosis occurs in aged animals and those with nutritional imbalances.

Traumatic Injuries

Fractures occur in all species with varying patterns: long bone fractures in large animals often require surgical intervention, vertebral fractures can cause paralysis, pelvic fractures affect parturition in females, and skull fractures may cause neurological deficits.

Skeletal Development and Growth

Ossification Processes

Bones develop through two primary mechanisms: intramembranous ossification (flat bones like skull bones) forms directly from mesenchymal tissue, while endochondral ossification (long bones) replaces a cartilage model with bone tissue.

Growth Plates and Maturity

Physeal (growth plate) closure timing varies by species and specific bone: smaller species reach skeletal maturity earlier (cats by 10-12 months, dogs by 12-18 months depending on size), while larger species mature later (horses by 5-6 years, cattle by 3-4 years). Nutritional factors and genetics significantly influence growth rates.

Sexual Dimorphism

Males typically exhibit larger overall skeletal size, more robust bone structure, larger muscle attachment sites, and more prominent features (horns, tusks). Females demonstrate broader pelvic inlets adapted for parturition, lighter overall bone structure, and less pronounced muscle attachment sites.

Nutritional Requirements for Skeletal Health

Essential Minerals

Calcium and phosphorus must be provided in proper ratios (typically 1.2:1 to 2:1 depending on species). Vitamin D facilitates calcium absorption and bone mineralization. Magnesium, zinc, copper, and manganese serve as cofactors in bone metabolism.

Critical Growth Periods

Rapid growth phases require carefully balanced nutrition to prevent developmental orthopedic diseases. Overfeeding during growth can be as detrimental as underfeeding, particularly in large-breed dogs and horses. Species-specific requirements must be considered when formulating diets.

Conclusion

The comparative analysis of domestic animal skeletons reveals both remarkable similarities reflecting shared mammalian ancestry and striking differences representing evolutionary adaptations to diverse ecological niches and human-directed selection. From the agile, flexible skeleton of the cat to the powerful, weight-bearing structure of the horse, each species demonstrates skeletal modifications perfectly suited to its lifestyle and function.

Understanding these comparative anatomical features provides essential knowledge for veterinary professionals, animal scientists, and anyone working with domestic animals. This knowledge enables better health management, improved husbandry practices, more effective breeding programs, and deeper appreciation for the remarkable diversity of form and function achieved through evolutionary processes.

As we continue to work with and care for domestic animals, this foundational knowledge of skeletal anatomy remains indispensable, informing everything from routine health care to advanced surgical procedures, and from understanding behavioral capabilities to predicting potential health challenges. The skeleton truly represents the structural foundation upon which all other body systems depend, and its proper development, maintenance, and function are essential to animal health, welfare, and productivity.