Lyme disease is a bacterial infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi (and related species like Borrelia afzelii in Europe), transmitted primarily through bites from infected black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis in North America, Ixodes ricinus in Europe). It’s most common in temperate regions of North America, Europe, and Asia, with peak incidence in spring and summer when ticks are active.

Lyme Disease Symptoms

Symptoms vary by stage and can differ between individuals. If untreated, the disease progresses through three stages:

Early Localized Stage (3–30 days post-bite)

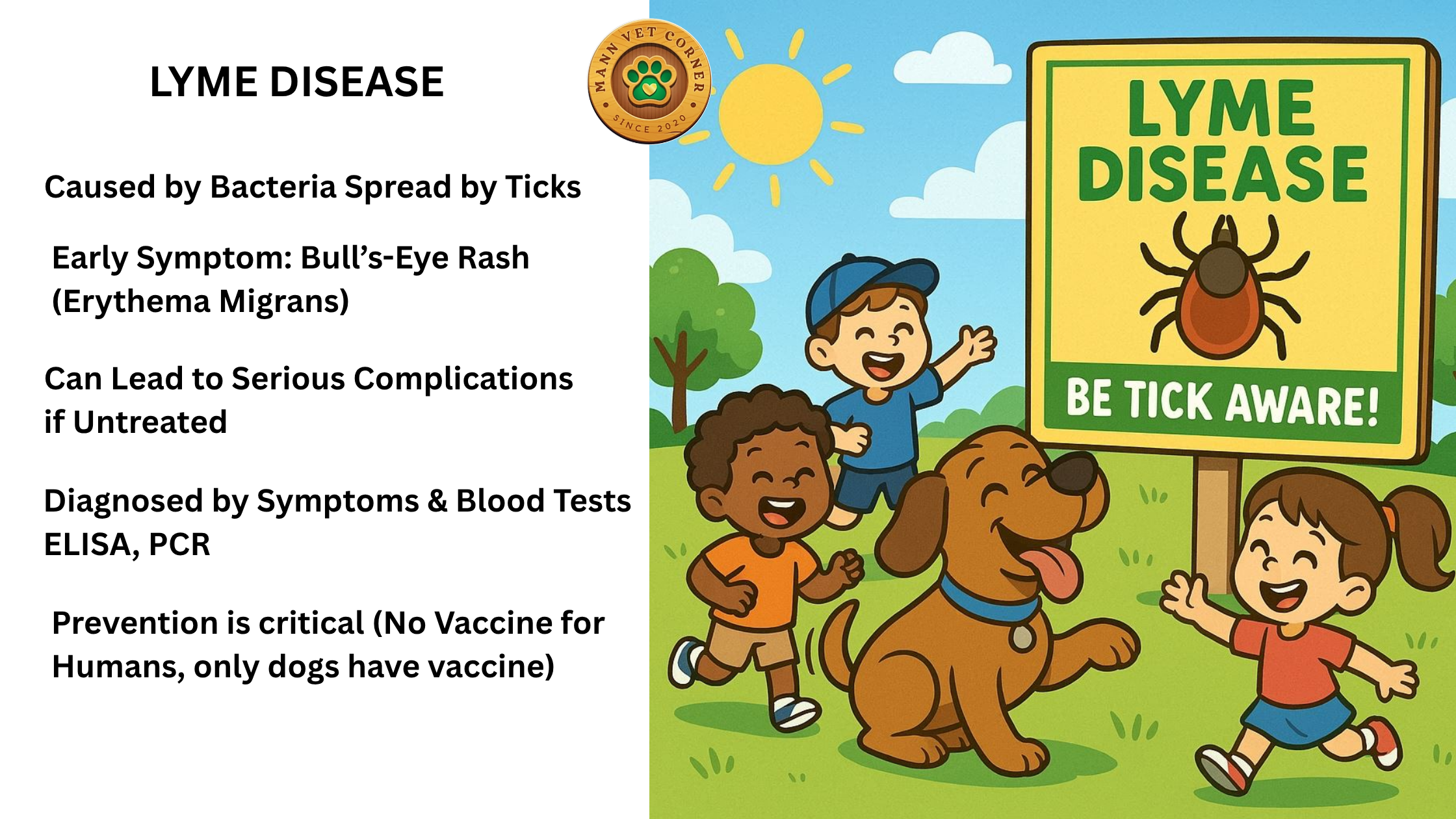

- Erythema migrans (EM) rash: A hallmark symptom, appearing in 70–80% of cases. It’s a red, expanding rash, often with a bull’s-eye pattern, at the bite site. Usually painless and not itchy.

- Flu-like symptoms: Fever, chills, fatigue, headache, muscle/joint aches, swollen lymph nodes.

Early Disseminated Stage (weeks to months post-bite)

- Multiple EM rashes: Spread to other body areas.

- Neurological issues: Facial palsy (Bell’s palsy), meningitis, neck stiffness, nerve pain.

- Cardiac problems: Heart palpitations, irregular heartbeat (Lyme carditis, rare).

- Joint pain: Intermittent arthritis, especially in large joints like knees.

- Fatigue and cognitive difficulties: Memory issues, difficulty concentrating.

Late Disseminated Stage (months to years post-bite)

- Chronic arthritis: Persistent joint inflammation, especially in knees.

- Neurological symptoms: Encephalopathy, numbness, tingling, memory impairment.

- Skin changes: Rare cases of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (more common in Europe).

Note: Not all patients progress through all stages, and symptoms can overlap. Some experience “post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome” (PTLDS), with lingering fatigue, pain, or cognitive issues after treatment, though the cause is debated.

Lyme Disease Life Cycle

The life cycle of Lyme disease involves the tick vector, Borrelia bacteria, and reservoir hosts. Ticks (Ixodes species) have a two-year life cycle with four stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult.

- Egg Stage: Female ticks lay eggs in spring. Eggs hatch into larvae by summer, which are not yet infected with Borrelia.

- Larval Stage: Larvae feed on small mammals (e.g., white-footed mice) or birds, which are reservoir hosts for Borrelia. If the host is infected, larvae acquire the bacteria.

- Nymphal Stage: Infected larvae molt into nymphs, active in spring/summer of the next year. Nymphs are tiny (<2 mm) and responsible for most human infections due to their size and peak activity during warm months.

- Adult Stage: Nymphs molt into adults in fall. Adults feed on larger mammals (e.g., deer), which amplify tick populations but are poor reservoirs for Borrelia. Adult ticks can transmit Lyme to humans, though less commonly than nymphs.

Transmission: Borrelia is transmitted when an infected tick feeds for 36–48 hours or more. The bacteria multiply in the tick’s gut and migrate to its salivary glands during feeding, infecting the host.

Animal vs. Human Lyme Disease

Lyme disease affects both animals and humans, but manifestations and management differ.

Animals

- Commonly affected: Dogs, horses, and cattle. Cats are less susceptible.

- Reservoir hosts: Small mammals (e.g., white-footed mice, shrews) and birds maintain Borrelia in nature but rarely show symptoms. Deer are not reservoirs but are critical for tick reproduction.

- Symptoms in animals:

- Dogs: Lameness, joint swelling, fever, lethargy, loss of appetite. Kidney damage (Lyme nephropathy) is a rare but severe complication.

- Horses: Lameness, stiffness, neurological issues (rare).

- Cattle: Joint swelling, reduced milk production.

- Many animals (e.g., mice) are asymptomatic carriers.

- Diagnosis: Based on symptoms, history of tick exposure, and blood tests (e.g., ELISA, Western blot, or C6 antibody test in dogs). Tests may detect exposure but not always active disease.

- Treatment: Antibiotics (e.g., doxycycline, amoxicillin) for 2–4 weeks. Response is usually rapid in dogs and horses.

- Prevention: Tick control (collars, topical treatments), vaccines (available for dogs in endemic areas), and environmental management (e.g., clearing tall grass).

Humans

- Symptoms: As described above, with a broader range of systemic effects (e.g., neurological, cardiac) compared to animals. The EM rash is unique to humans.

- Diagnosis: Clinical evaluation (especially EM rash), history of tick exposure, and serologic tests (ELISA followed by Western blot). Early-stage testing can yield false negatives due to delayed antibody response.

- Treatment: Antibiotics (doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime) for 10–21 days, depending on stage. IV antibiotics (e.g., ceftriaxone) are used for severe neurological or cardiac cases.

- Prevention: Tick bite avoidance (protective clothing, DEET repellents), prompt tick removal, and checking for ticks after outdoor activities. No human vaccine is currently available (a new vaccine is in clinical trials as of 2025).

- Chronic issues: PTLDS is a human-specific concern, with debated causes (persistent infection vs. immune dysfunction). Animals rarely show chronic symptoms post-treatment.

Key Differences Animal vs. Human Lyme Disease

| Aspect | Animals (Dogs, Wildlife) | Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Fever, lameness, swollen joints, lethargy | Rash, flu-like symptoms, neurological issues |

| Diagnosis | Blood tests (4Dx test for dogs) | ELISA/Western blot, clinical signs |

| Treatment | Doxycycline, amoxicillin | Doxycycline, amoxicillin, cefuroxime |

| Prevention | Tick collars, vaccines (for dogs), tick checks | Tick repellents, protective clothing, tick checks |

| Chronic Effects | Can develop kidney disease (dogs) | Possible PTLDS (chronic fatigue, joint pain) |

Note:

Dogs can get Lyme disease but cannot directly transmit it to humans.

Deer are key hosts for adult ticks but do not carry Lyme bacteria.

White-footed mice are the main reservoir for Borrelia in nature.

Additional Notes

- Geographic variation: Symptoms and Borrelia species differ by region. For example, B. afzelii in Europe causes more skin manifestations, while B. burgdorferi in North America is linked to arthritis.

- Co-infections: Ticks can transmit other pathogens (e.g., Anaplasma, Babesia), complicating symptoms in both humans and animals.

- Public health: Lyme disease incidence is rising due to cli mate change, expanding tick ranges, and increased human exposure in suburban areas.

I have been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this site. Thank you, I¦ll try and check back more often. How frequently you update your web site?

Welcome back—and thank you for the kind words! I’m glad the site still resonates with you. I update Mann Vet Corner regularly on daily basis with new article.

Feel free to check in often or subscribe to stay in the loop. Your engagement means a lot!