Livestock farmers worldwide face constant challenges protecting their herds from infectious diseases. Blue Tongue Disease (BT) is a severe, insect-borne viral disease affecting sheep, cattle, goats, deer, and other ruminants, spread by biting midges, causing fever, swelling (especially of face/tongue, turning it blue), lameness, and potential death, though usually mild in cattle but highly fatal in sheep, posing no threat to humans but significant economic risk to livestock. This comprehensive guide explores everything you need to know about this midge-borne illness that threatens sheep, cattle, and goats across multiple continents.

What Is Blue Tongue Disease? Understanding This Viral Livestock Infection

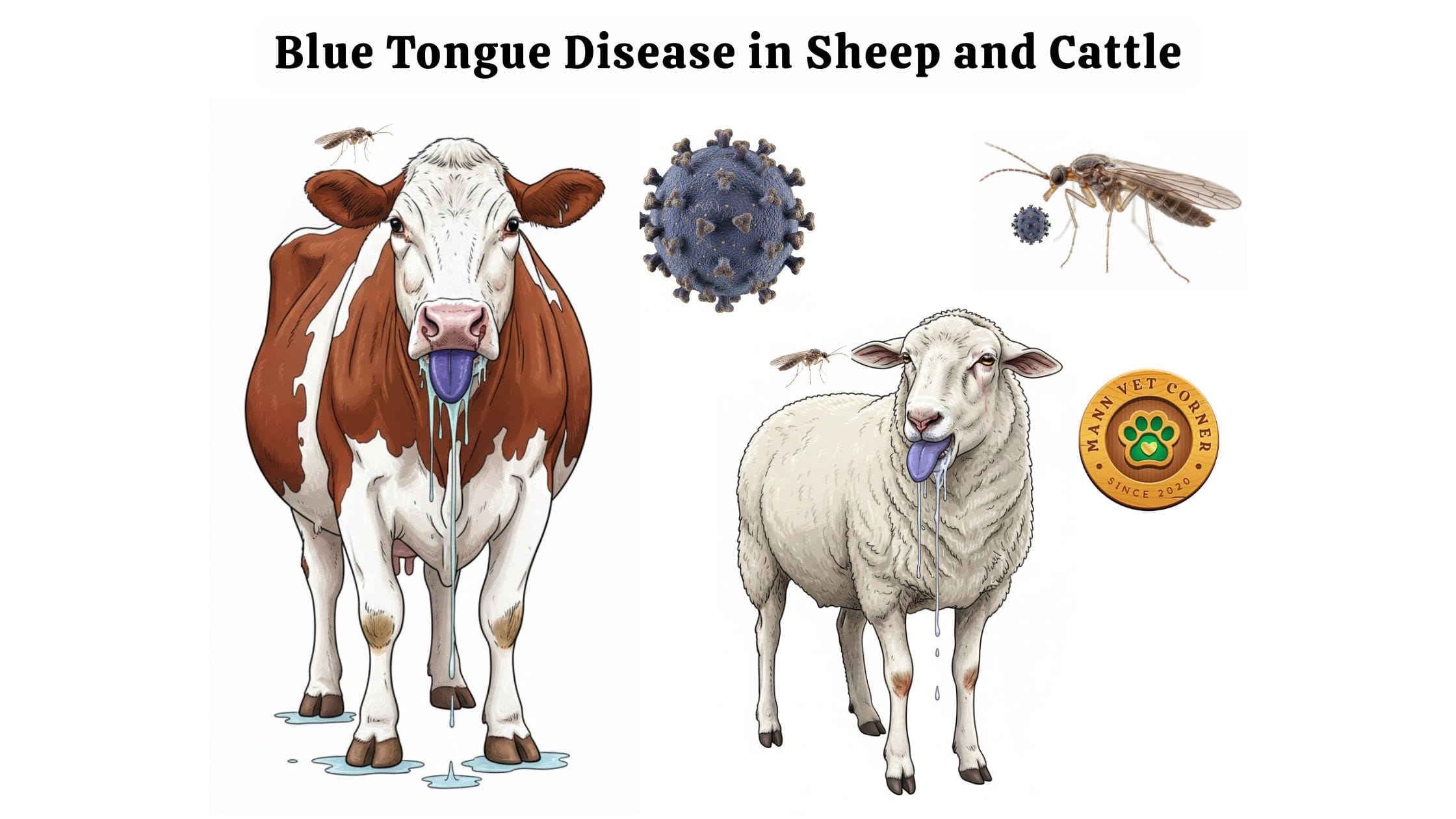

Blue tongue disease (BT) is a severe viral infection that attacks ruminant animals through biting midge transmission. The disease gets its distinctive name from the characteristic blue or purple discoloration that appears on infected animals’ tongues during advanced stages.

Farmers and veterinarians recognize this condition as a non-contagious disease that spreads exclusively through insect vectors rather than direct animal contact. The bluetongue virus belongs to the Orbivirus family and causes significant economic losses in livestock industries globally.

How Blue Tongue Disease Affects Different Livestock Species

The severity of bluetongue infection varies dramatically depending on the animal species involved:

Sheep Experience the Most Severe Cases

Sheep suffer the highest mortality rates and most dramatic symptoms when infected with bluetongue virus. Clinical signs in sheep progress rapidly and often prove fatal without immediate veterinary intervention. Mortality rates in susceptible sheep populations can reach 30% or higher during major outbreaks.

Cattle Often Become Silent Carriers

Cattle typically show mild symptoms or remain completely asymptomatic despite carrying active bluetongue virus. This makes cattle particularly dangerous as disease reservoirs since infected animals continue spreading the virus to midges without showing obvious signs of illness. Farmers may not realize their cattle herd harbors the infection until nearby sheep flocks begin showing symptoms.

Other Ruminants Show Variable Responses

Goats, deer, bison, camels, and antelope can all contract bluetongue disease with varying degrees of severity. Goats generally experience moderate symptoms, while wild deer populations sometimes suffer significant mortality during outbreak years.

What Causes Blue Tongue Disease? The Orbivirus Behind the Outbreak

The bluetongue virus (BTV) causes this livestock disease through a complex transmission cycle. BTV, an Orbivirus, transmitted by Culicoides midges. Scientists have identified over 27 different serotypes of bluetongue virus worldwide, with different serotypes predominating in various geographic regions.

Understanding Bluetongue Virus Serotypes and Strain Variation

Each bluetongue virus serotype behaves as a distinct entity requiring specific immune responses. Animals vaccinated against one serotype remain vulnerable to infection from other serotypes. This creates significant challenges for vaccine development and outbreak prevention strategies.

European outbreaks in recent years have involved serotypes BTV-1, BTV-4, and BTV-8, while African regions contend with multiple endemic serotypes. The Americas face their own unique combinations of circulating bluetongue virus strains.

How Does Blue Tongue Disease Spread? The Role of Culicoides Midges

Understanding bluetongue transmission requires examining the crucial role of Culicoides biting midges. These tiny insects, barely visible to the naked eye, serve as the exclusive transmission vector for bluetongue virus between animals.

The Culicoides Midge Life Cycle and Disease Transmission

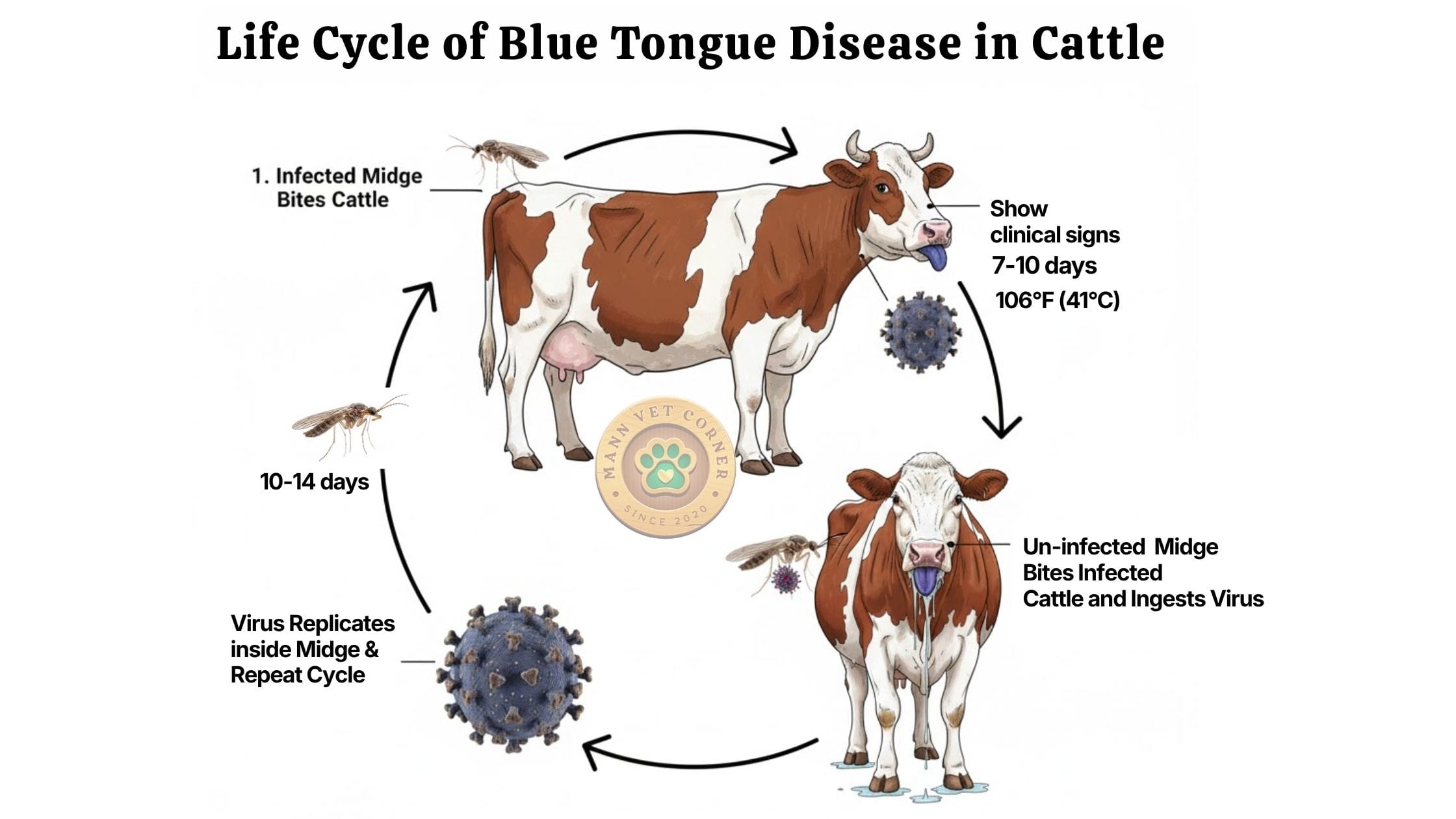

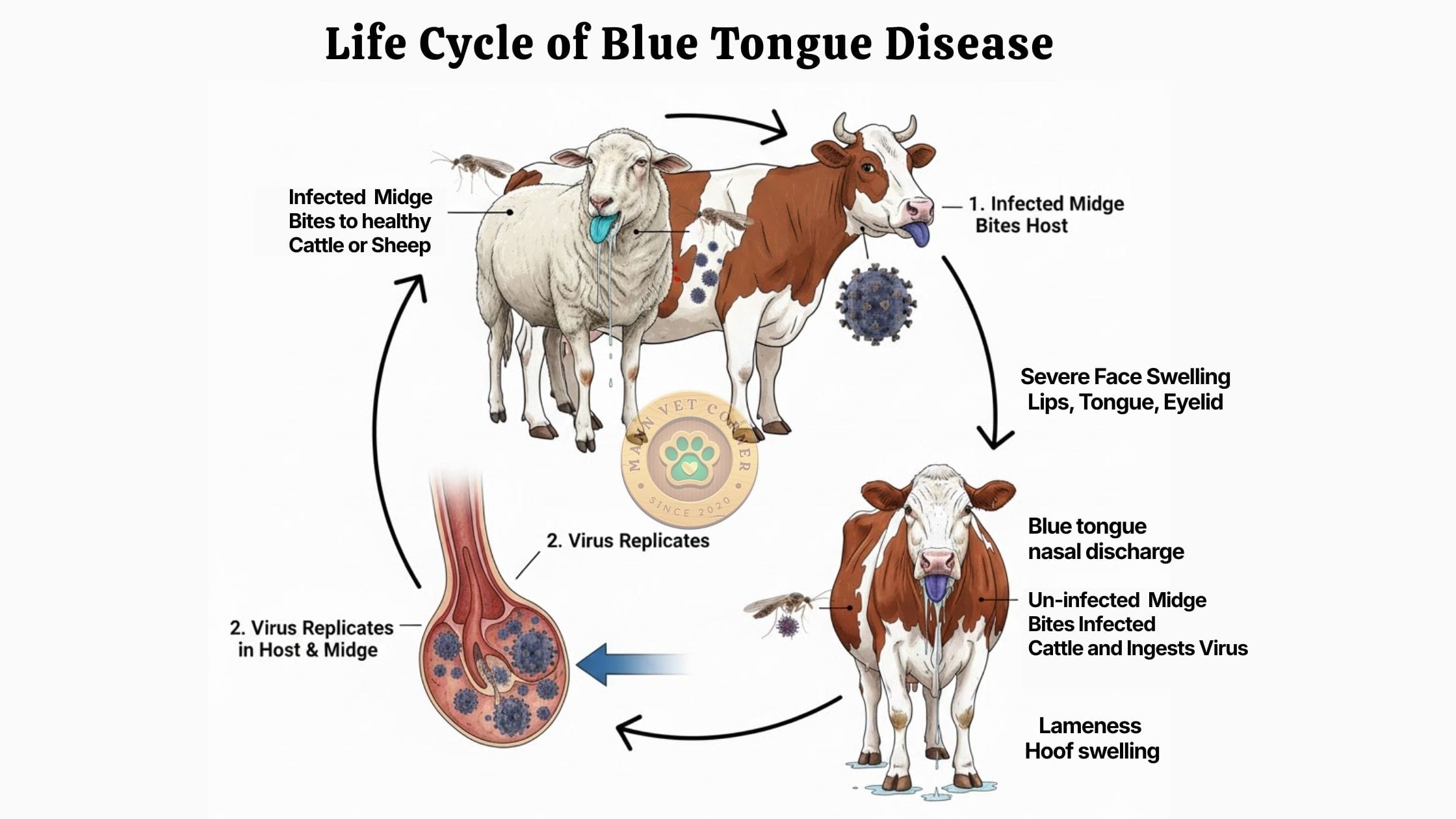

Culicoides midges thrive in warm, humid conditions near standing water where they breed. Female midges require blood meals for egg development, feeding primarily during dawn and dusk hours. When a midge bites an infected animal, it ingests bluetongue virus along with the blood meal.

The virus then replicates within the midge’s body over 10-14 days before the insect becomes capable of transmitting infection. Once infectious, the midge carries bluetongue virus for life and spreads disease to every subsequent animal it bites.

Critical Fact: Blue Tongue Disease Does Not Spread Between Animals

Many farmers initially worry about quarantining sick animals from healthy herd members. However, bluetongue virus cannot transmit through direct animal contact, shared feed, water sources, or respiratory secretions. Only infected midges spread the disease, making insect control the primary prevention strategy.

Recognizing Blue Tongue Disease Symptoms in Sheep: Early Warning Signs

Sheep farmers must recognize bluetongue symptoms quickly since early intervention significantly improves survival rates. The disease progresses through distinct stages with increasingly severe clinical signs.

Initial Stage Symptoms in Infected Sheep

The first symptoms appear 7-10 days after an infected midge bite. Affected sheep develop sudden high fever reaching 106°F (41°C) or higher. The animals become lethargic, separate from the flock, and lose interest in food and water.

Progressive Clinical Signs of Blue Tongue in Sheep

As the disease advances, more characteristic symptoms emerge:

Facial Swelling and Inflammation

Severe swelling affects the face, particularly around the muzzle, lips, ears, and eyelids. The facial swelling gives infected sheep a distinctly bloated appearance that experienced farmers recognize immediately.

Nasal and Oral Discharge

Thick mucus discharge flows from the nostrils, often containing blood. Excessive drooling accompanies oral inflammation as the mouth becomes too painful for normal swallowing. Foam may accumulate around the muzzle as secretions mix with saliva.

The Distinctive Blue Tongue

The tongue swells dramatically and turns blue, purple, or cyanotic due to impaired blood circulation. This hallmark symptom provides the disease its common name. In some cases, the tongue swells so severely it protrudes from the mouth.

Lameness and Hoof Complications

Inflammation of the coronary band where the hoof meets the leg causes severe lameness. Sheep may kneel on their front legs to relieve pressure or refuse to stand. Secondary bacterial infections of damaged hooves frequently develop, complicating recovery.

Skin Hemorrhages and Redness

Small bleeding points appear under the skin, particularly visible on areas with less wool coverage. The skin may redden and develop crusty lesions. Wool breaks and falls out easily from damaged follicles.

Late Stage Complications in Severe Cases

Sheep that survive the acute phase often face prolonged recovery periods. Pregnant ewes frequently abort. Survivors may suffer permanent hoof deformities, wool growth abnormalities, and chronic respiratory problems.

Blue Tongue Disease Symptoms in Cattle: Why Cattle Remain Disease Reservoirs

Cattle play a complex role in bluetongue epidemiology since most infections remain subclinical. Understanding cattle symptoms helps farmers implement appropriate monitoring and control measures.

Common Clinical Signs in Symptomatic Cattle

When cattle do show symptoms, they typically experience:

- Mild fever lasting several days

- Decreased appetite and reduced milk production

- General lethargy and depression

- Occasional nasal discharge

- Mild swelling around the head

- Temporary lameness

These symptoms rarely reach the severity seen in sheep and often resolve without treatment. However, infected cattle continue shedding virus in their blood for extended periods, serving as reservoirs for midge transmission.

Why Cattle Become Asymptomatic Carriers

Cattle have evolved greater resistance to bluetongue virus compared to sheep. Their immune systems control viral replication more effectively while tolerating persistent low-level infections. This biological difference makes cattle populations critical factors in disease spread patterns.

How Veterinarians Diagnose Blue Tongue Disease: Testing Methods Explained

Accurate diagnosis requires combining clinical observation with laboratory confirmation. Veterinarians employ multiple diagnostic approaches to confirm bluetongue infection.

Clinical Diagnosis Based on Symptoms

Experienced veterinarians often recognize bluetongue from characteristic clinical signs, particularly in sheep during known outbreak periods. The combination of facial swelling, blue tongue discoloration, lameness, and nasal discharge creates a distinctive clinical picture.

Serological Testing for Bluetongue Antibodies

Blood tests detecting antibodies against bluetongue virus confirm exposure and infection. Veterinary laboratories use ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) tests to identify antibodies specific to bluetongue virus. These tests reveal whether animals have encountered the virus previously or currently fight active infection.

PCR Testing for Viral Genetic Material

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests detect bluetongue virus genetic material directly in blood samples. PCR provides highly sensitive detection of active infections and can differentiate between different serotypes. This information helps authorities track which viral strains circulate in specific regions.

Differential Diagnosis: Ruling Out Similar Diseases

Veterinarians must distinguish bluetongue from other diseases causing similar symptoms:

- Foot and mouth disease

- Malignant catarrhal fever

- Peste des petits ruminants

- Contagious ecthyma (orf)

- Photosensitization

Laboratory testing becomes essential when clinical signs could indicate multiple possible diseases.

Blue Tongue Disease Treatment: Managing Infected Animals

No specific antiviral medication exists to eliminate bluetongue virus from infected animals. Treatment focuses on supportive care that helps animals survive while their immune systems fight the infection.

Supportive Care Protocols for Affected Livestock

Providing Comfortable Rest Areas

Sick animals need shelter from environmental stress. Housing in barns or shaded areas protects them from heat, cold, and additional insect exposure. Soft bedding reduces pressure on inflamed hooves and encourages rest.

Offering Soft, Palatable Feed

Painful mouth lesions and swollen tongues make eating difficult. Farmers should provide soft feeds like pelleted grain soaked in water, fresh green grass, or alfalfa hay. Some animals tolerate liquid supplements or gruel-like mixtures better than solid feed.

Ensuring Water Access

Dehydration threatens already weakened animals. Placing water sources close to resting areas and sometimes offering water by bucket or tube feeding maintains hydration. Some farmers add electrolytes to drinking water during recovery.

Anti-inflammatory Medications

Veterinarians may prescribe anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce fever, pain, and swelling. These medications improve animal comfort and may enhance survival rates by reducing tissue damage from excessive inflammation.

Treating Secondary Bacterial Infections

Antibiotics address secondary bacterial infections affecting damaged hooves, skin lesions, or respiratory passages. While antibiotics don’t fight the virus directly, they prevent complications that could prove fatal.

Recovery Time and Prognosis

Sheep that survive acute bluetongue disease typically require several weeks for complete recovery. Mortality risk remains highest during the first week of obvious symptoms. Animals showing improvement after 10-14 days generally survive with appropriate care.

Preventing Blue Tongue Disease: Vaccination Strategies That Work

Vaccination represents the most effective method for protecting susceptible animals from bluetongue infection. Modern vaccines provide strong immunity when administered correctly.

Types of Bluetongue Vaccines Available

Modified Live Vaccines

These vaccines contain weakened bluetongue virus that stimulates strong immune responses without causing disease. Modified live vaccines typically provide robust, long-lasting immunity but require careful handling and may not suit all farm situations.

Inactivated Vaccines

Killed virus vaccines offer safety advantages since they cannot cause infection under any circumstances. However, inactivated vaccines often require booster doses to maintain protective immunity levels.

Serotype-Specific Protection

All current bluetongue vaccines protect only against specific serotypes included in their formulation. Farmers must use vaccines containing the serotypes actually circulating in their region. Vaccination against BTV-8 provides no protection against BTV-4 infection.

Implementing Effective Vaccination Programs

Timing Vaccinations Before Midge Season

Vaccinate animals at least 3-4 weeks before expected midge activity begins. This gives the immune system time to develop protective antibodies before exposure risk increases. Most regions have predictable seasonal patterns of Culicoides activity that guide vaccination timing.

Booster Doses for Sustained Immunity

Initial vaccination series often require two doses given 3-4 weeks apart, followed by annual boosters. Pregnant ewes vaccinated before breeding pass temporary immunity to lambs through colostrum, providing early protection.

Herd Immunity Considerations

Vaccinating high percentages of susceptible animals (typically 70-80% or more) reduces overall disease transmission by limiting the number of infectious hosts available to midges. This protects even unvaccinated individuals through herd immunity effects.

Controlling Culicoides Midges: Reducing Disease Transmission Risk

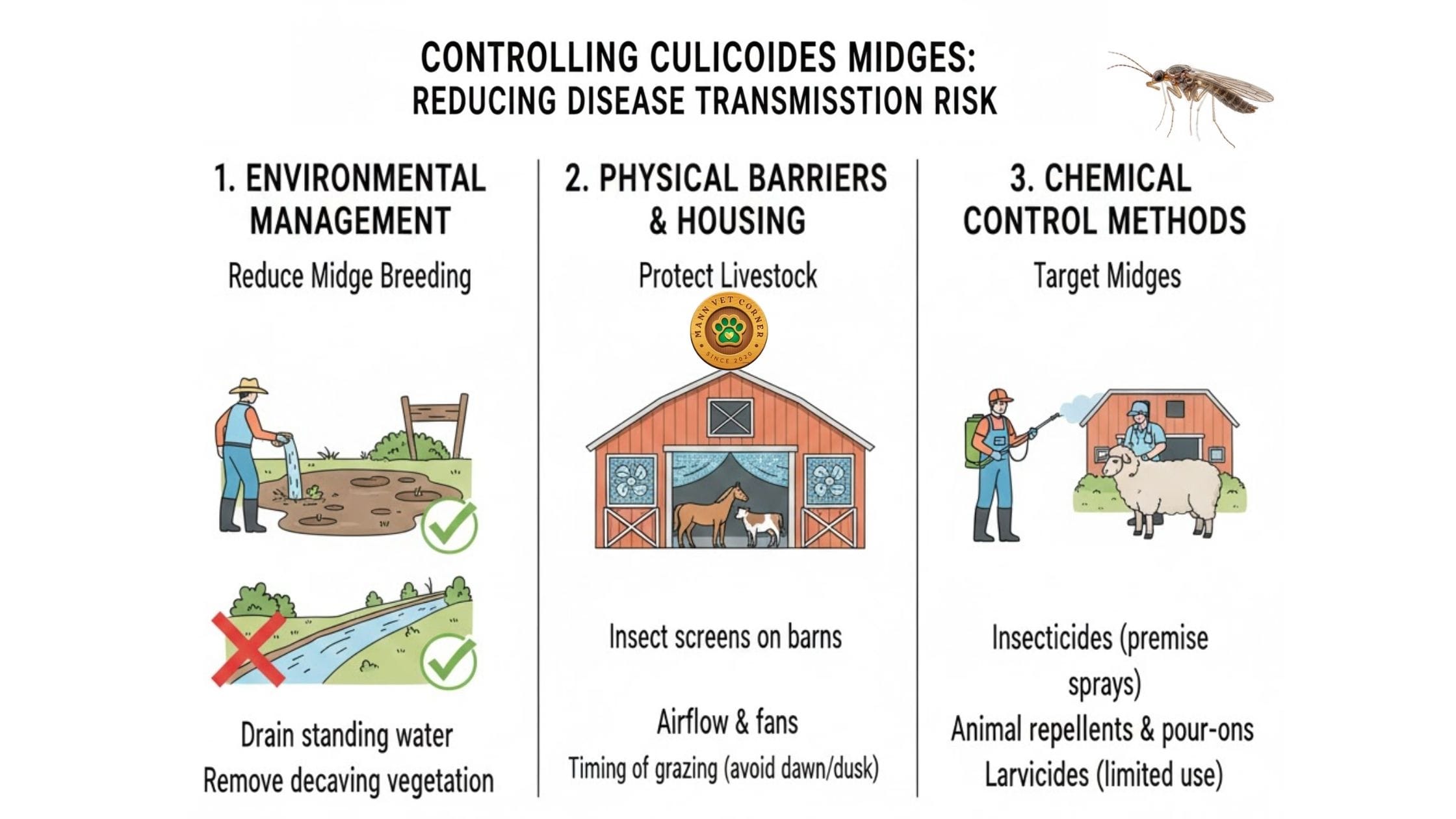

Since midges exclusively transmit bluetongue virus, controlling these insects directly reduces disease spread. Integrated pest management combines multiple control methods for best results.

Environmental Management to Reduce Midge Breeding

Eliminating Standing Water

Culicoides larvae develop in moist soil and muddy areas around water sources. Draining unnecessary standing water, improving pasture drainage, and removing mud accumulation reduces midge breeding habitat.

Managing Manure and Organic Material

Midges breed prolifically in wet manure and decomposing organic material. Regular manure removal, composting that generates heat sufficient to kill larvae, and maintaining dry conditions around barns all help control midge populations.

Physical Barriers and Housing Strategies

Fine Mesh Screening

Culicoides midges measure less than 3mm in length, passing easily through standard fly screens. Special fine-mesh screening (mesh size <1mm) on barn windows and doors excludes midges while maintaining ventilation.

Housing Animals During Peak Activity

Bringing susceptible animals indoors during dawn and dusk hours when midges feed most actively reduces bite exposure. This proves particularly valuable for high-value breeding stock during high-risk periods.

Chemical Control Methods

Approved Insecticides for Livestock

Pour-on and spray insecticides containing pyrethroids provide some protection against midge bites. However, the small size of Culicoides makes them harder to control than larger flies. Regular reapplication becomes necessary since protection wears off quickly.

Environmental Insecticide Applications

Treating midge breeding habitats with larvicides reduces adult populations. This requires identifying breeding sites and applying products at times when larvae are present and vulnerable.

Monitoring Midge Populations

Light traps and suction traps capture midges for monitoring programs that track population levels and seasonal activity patterns. This data helps farmers time preventive measures more effectively.

Movement Restrictions and Biosecurity: Preventing Disease Spread

Government authorities implement various control measures during bluetongue outbreaks to prevent geographic spread.

Quarantine Zones and Restriction Areas

Regions with confirmed bluetongue cases typically fall under movement restrictions. Authorities establish restriction zones where animal movements require permits, testing, and sometimes vaccination before transport. These zones typically extend well beyond immediate outbreak areas to create buffer zones.

Pre-Movement Testing Requirements

Animals moving from restriction zones to disease-free areas often require testing to confirm they don’t carry active infections. PCR testing identifies infected animals while serological testing reveals previous exposure.

International Trade Implications

Many countries restrict importation of ruminants and genetic material from regions where bluetongue remains endemic. These restrictions significantly impact international livestock trade and genetic improvement programs.

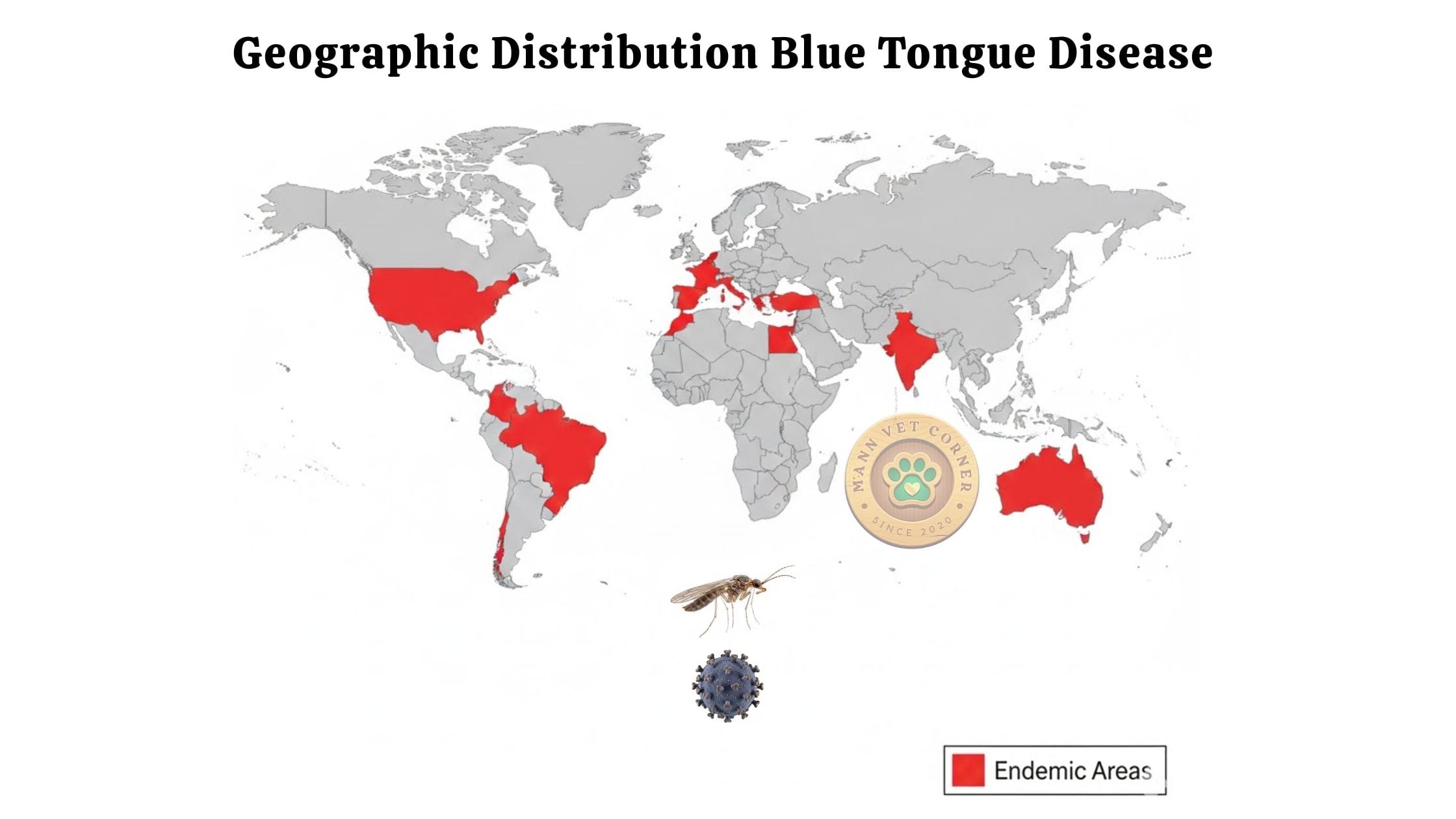

Geographic Distribution: Where Blue Tongue Disease Occurs Worldwide

Bluetongue disease affects livestock operations across multiple continents, with distribution closely following Culicoides midge habitat ranges.

Endemic Regions With Persistent Bluetongue

Africa and the Middle East

Multiple bluetongue serotypes circulate continuously across sub-Saharan Africa and Middle Eastern countries. The disease originated in Africa where it has afflicted livestock for centuries. Year-round midge activity in tropical regions maintains constant transmission.

Southern Europe and Mediterranean Basin

Climate change has enabled Culicoides midges to establish permanent populations across southern Europe. Countries like Spain, Italy, Greece, and southern France now contend with regular bluetongue outbreaks during warm months.

Asia and Oceania

India, Pakistan, and Southeast Asian nations face endemic bluetongue. Australia experiences sporadic outbreaks in northern regions where tropical conditions favor midge populations.

The Americas

The United States, particularly southern states, deals with endemic bluetongue in wildlife and livestock. Central and South American countries also report regular disease activity.

Recent Range Expansion in Northern Regions

Warming temperatures have pushed Culicoides midge ranges northward into previously unaffected areas. Northern European countries including the United Kingdom, Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Denmark have reported significant outbreaks since the early 2000s. This expansion poses new challenges for farmers unaccustomed to managing bluetongue risk.

Economic Impact: Understanding the True Cost of Blue Tongue Disease

The financial burden of bluetongue extends far beyond direct animal losses, affecting entire agricultural economies.

Direct Production Losses

Mortality in Valuable Breeding Stock

Death losses hit hardest when disease kills high-value purebred breeding animals. A single outbreak can eliminate years of genetic improvement work and devastate breeding programs.

Reduced Productivity in Survivors

Recovered animals often show decreased production. Ewes produce less wool of lower quality. Milk production drops in dairy cattle. Reproductive performance declines for months or years following infection.

Abortion and Reproductive Failure

Pregnant animals frequently abort following bluetongue infection. Even animals that carry pregnancies to term may produce weak offspring. This disrupts breeding schedules and reduces lamb and calf crops.

Indirect Economic Costs

Veterinary Expenses and Treatment Costs

Diagnostic testing, medications, and intensive nursing care for sick animals add substantial expenses during outbreaks. Large-scale vaccination programs require significant investment.

Trade Restrictions and Market Access

Movement restrictions prevent farmers from accessing normal markets. Export bans devastate operations dependent on international trade. Even after outbreaks end, rebuilding disease-free status and regaining market access takes years.

Surveillance and Control Program Costs

Government surveillance programs, midge monitoring, and disease control measures require substantial public funding. These costs ultimately affect taxpayers and consumers through higher food prices.

Blue Tongue Disease and Human Health: Why You Should Not Worry

One of the most common questions farmers ask concerns potential human health risks from bluetongue disease.

Bluetongue Virus Does Not Infect Humans

Scientific research over many decades confirms that bluetongue virus poses no threat to human health. The virus cannot infect human cells or cause illness in people. This holds true regardless of exposure level.

Safe Handling of Infected Animals

Farmers and veterinarians can safely handle infected animals without personal health concerns. No special protective equipment beyond standard farm hygiene practices is necessary when caring for bluetongue patients.

Safe Consumption of Meat and Dairy Products

Products from infected animals remain completely safe for human consumption. Bluetongue virus does not survive cooking, and moreover, cannot infect humans even if consumed. However, sick animals typically get withheld from food chains due to poor quality rather than safety concerns.

Climate Change and Blue Tongue Disease: The Growing Threat

Environmental changes influence bluetongue distribution and outbreak frequency in complex ways.

How Warming Temperatures Expand Midge Habitat

Rising temperatures extend the geographic range and seasonal activity period of Culicoides midges. Regions previously too cold for year-round midge survival now support overwintering populations. Longer warm seasons increase the number of midge generations per year, multiplying transmission opportunities.

Extreme Weather Events and Disease Risk

Unusual weather patterns create ideal conditions for midge population explosions. Warm, wet springs followed by hot summers produce massive midge populations. Conversely, drought conditions that create small, concentrated water sources may also favor midge breeding.

Preparing for Future Outbreaks

Livestock industries must adapt to increased bluetongue risk through enhanced surveillance, expanded vaccination programs, and improved biosecurity measures. Research into new vaccine technologies and midge control methods continues as climate change promises to intensify bluetongue challenges.

Future Developments: Research and New Control Technologies

Scientific advances offer hope for improved bluetongue management in coming years.

Next-Generation Vaccines

Researchers work on developing broader-spectrum vaccines that protect against multiple serotypes simultaneously. Cross-protective vaccines would simplify vaccination programs and provide better coverage against diverse virus strains.

Genetic Resistance in Livestock

Breeding programs aim to enhance natural resistance to bluetongue disease. Identifying genetic markers associated with disease resistance allows selection of naturally resistant animals for breeding.

Novel Midge Control Approaches

Innovative control methods under investigation include biological control using midge parasites or pathogens, genetic modification techniques to reduce midge populations, and improved attractants for monitoring and trapping systems.

Practical Management Guide: Protecting Your Flock or Herd

This section provides actionable steps livestock farmers can implement immediately to reduce bluetongue risk.

Risk Assessment for Your Operation

Evaluate your farm’s specific risk factors:

- Geographic location relative to known bluetongue zones

- Proximity to wetlands or areas with high midge populations

- Species composition (sheep, cattle, goats) and their susceptibility levels

- Seasonal patterns of midge activity in your region

- Previous disease history on your farm or in your area

Developing a Comprehensive Control Plan

Step 1: Implement Preventive Vaccination

Work with your veterinarian to select appropriate vaccines for circulating serotypes in your region. Establish a vaccination schedule that ensures immunity before midge season begins. Maintain detailed records of all vaccinations.

Step 2: Enhance Midge Control

Survey your property for midge breeding sites and eliminate them where possible. Improve drainage in low-lying areas. Manage manure to prevent wet accumulation. Consider housing susceptible animals during peak midge activity periods.

Step 3: Establish Monitoring Systems

Train yourself and farm staff to recognize early bluetongue symptoms. Check animals daily during high-risk seasons. Report suspected cases to veterinary authorities immediately for quick diagnosis and response.

Step 4: Prepare Emergency Response

Maintain supplies needed for supportive care of sick animals. Establish relationships with veterinarians before emergencies occur. Develop isolation areas for symptomatic animals to facilitate treatment.

Step 5: Maintain Biosecurity

Follow quarantine requirements when purchasing new animals. Request testing certificates showing disease-free status. Isolate new arrivals for observation periods before mixing with existing herds.

Working With Veterinary Authorities

Cooperate fully with government surveillance and control programs. These programs protect individual farms while safeguarding entire regional livestock industries. Report unusual symptoms promptly even if you suspect other causes.

Conclusion: Managing Blue Tongue Disease for Long-Term Livestock Health

Blue tongue disease presents serious challenges for livestock farmers, but effective management strategies exist. Understanding transmission through Culicoides midges rather than direct contact fundamentally shapes appropriate control approaches.

Vaccination remains the cornerstone of effective prevention for susceptible sheep, goats, and other ruminants. Combined with strategic midge control, environmental management, and careful biosecurity, vaccination programs dramatically reduce disease incidence and severity.

The expanding geographic range of bluetongue disease driven by climate change means more farmers will face this challenge in coming years. Staying informed about regional disease status, maintaining updated vaccination programs, and implementing integrated control strategies will prove essential for successful livestock operations.

Early recognition of symptoms leads to better outcomes through prompt supportive care. While no antiviral cure exists, attentive nursing care saves many animals that would otherwise succumb to complications.

Ultimately, protecting livestock from blue tongue disease requires sustained commitment to prevention rather than reactive crisis management. Farmers who invest in comprehensive control programs protect not only their own operations but contribute to broader community disease suppression that benefits all livestock producers in their region.