Avian aspergillosis is a significant respiratory disease affecting birds, caused by fungi from the genus Aspergillus. This condition poses a serious threat to poultry, wild birds, and pet species alike, often leading to high morbidity and mortality if not addressed promptly. Understanding its etiology, host susceptibility, incubation period, clinical signs, pathogenesis, postmortem findings, and treatment options is crucial for bird owners, veterinarians, and wildlife enthusiasts. In this blog, we’ll dive into each aspect of avian aspergillosis to provide a clear, professional, and easy-to-read overview.

Etiology: The Root Cause of Avian Aspergillosis

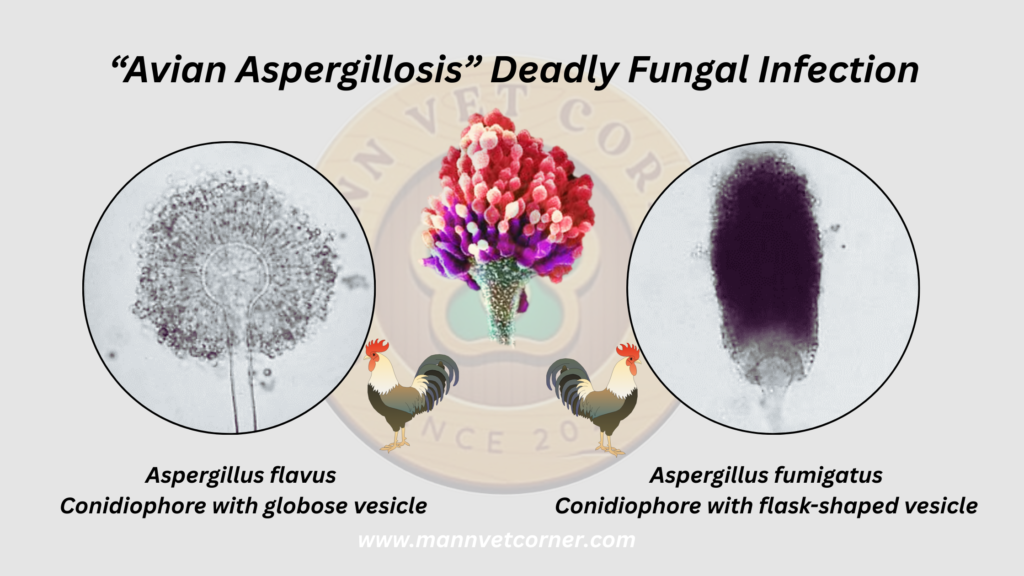

Avian aspergillosis is primarily caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, though other species like Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus niger can also be responsible. These fungi are ubiquitous in the environment, thriving in decaying organic matter such as moldy feed, straw, or damp bedding. The disease develops when birds inhale fungal spores (conidia), which are tiny, lightweight structures that easily become airborne. Poor ventilation, high humidity, and contaminated surroundings increase the likelihood of exposure. While the fungus itself isn’t inherently aggressive, it becomes pathogenic under conditions that weaken a bird’s immune system or when spore concentrations are unusually high.

Host Susceptibility: Who’s at Risk?

Birds of all kinds can contract avian aspergillosis, but susceptibility varies. Young birds, especially chicks and fledglings, are highly vulnerable due to their underdeveloped immune systems. Species like turkeys, penguins, waterfowl (e.g., ducks and geese), and raptors (e.g., falcons and hawks) are particularly prone to infection. Stress factors—such as overcrowding, malnutrition, prolonged antibiotic use, or concurrent diseases—further increase risk by compromising immunity. Healthy adult birds in clean, well-ventilated environments are less likely to succumb, but no bird is entirely immune if exposed to a heavy spore load.

Incubation Period: How Long Before Symptoms Appear?

The incubation period for avian aspergillosis isn’t fixed and can range from a few days to several weeks, depending on the bird’s health, the number of spores inhaled, and environmental conditions. In acute cases, where exposure is overwhelming, symptoms may emerge within 2-5 days. Chronic infections, often seen in stressed or immunocompromised birds, develop more slowly, with signs appearing over weeks or even months. This variability makes early detection challenging, underscoring the importance of monitoring at-risk birds closely.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Recognizing the Disease

The symptoms of avian aspergillosis depend on whether the infection is acute or chronic.

Acute Cases: Sudden, severe respiratory distress, including rapid breathing, gasping, and open-mouthed breathing. Other signs include lethargy, loss of appetite, and weight loss.

Chronic Cases: More subtle, with gradual onset of symptoms like nasal discharge, voice changes (e.g., loss of vocalization in parrots), and a fluffed-up appearance due to discomfort. Respiratory involvement is the hallmark, but the fungus can spread to other organs, causing neurological signs (e.g., head tilting or tremors) or digestive issues (e.g., vomiting). In poultry flocks, a sudden drop in egg production or poor growth rates may signal an outbreak. These diverse symptoms often mimic other illnesses, making veterinary diagnosis essential.

Respiratory involvement is the hallmark of this disease, but the fungus can spread to other organs, causing neurological signs (e.g., head tilting or tremors) or digestive issues (e.g., vomiting). In poultry flocks, a sudden drop in egg production or poor growth rates may signal an outbreak. These diverse symptoms often mimic other illnesses, making veterinary diagnosis essential.

Morbidity and Mortality: The Toll on Bird Populations

Avian aspergillosis can devastate bird populations, particularly in confined settings like poultry farms or aviaries. Morbidity rates—the percentage of birds affected—can reach 50-100% in outbreaks, especially among susceptible species or young birds. Mortality rates vary widely, from 10% in mild cases to over 90% in severe, untreated outbreaks. Factors like delayed treatment, high spore exposure, and underlying health issues drive these grim statistics. In wild bird populations, such as penguins or raptors in rehabilitation centers, the disease can wipe out entire groups if not controlled.

Pathogenesis: How the Disease Progresses

Once inhaled, Aspergillus spores lodge in the bird’s respiratory system, typically the air sacs or lungs. In healthy birds, immune defenses may clear the spores before they cause harm. However, in susceptible individuals, the spores germinate into thread-like structures called hyphae, which invade tissues and release toxins. This triggers inflammation, tissue damage, and the formation of granulomas (small, nodular lesions). In acute cases, rapid fungal growth overwhelms the respiratory system, leading to oxygen deprivation and death. In chronic cases, the infection spreads slowly, affecting multiple organs like the liver, kidneys, or brain, causing prolonged illness and debilitation.

Postmortem Findings: What the Necropsy Reveals

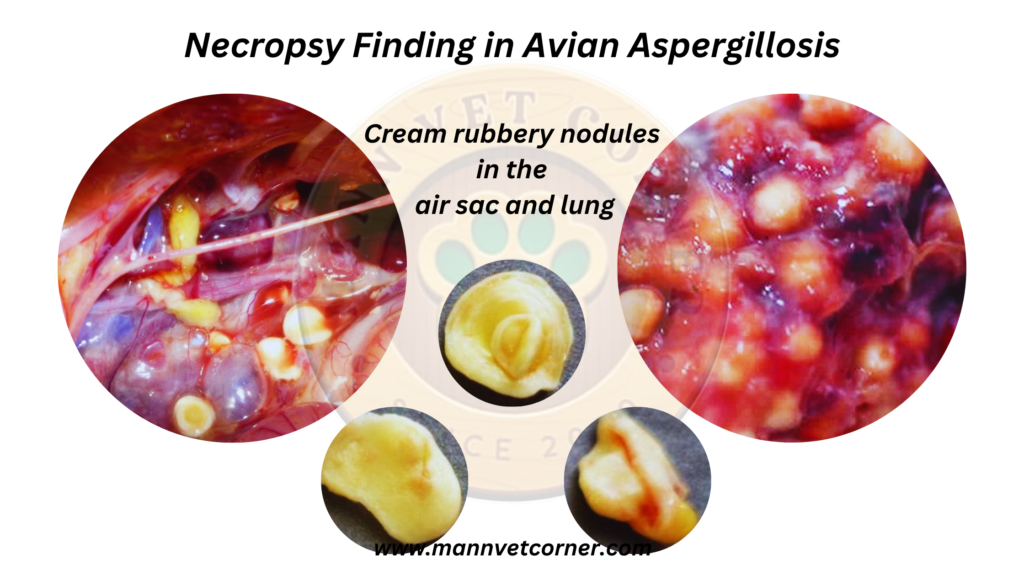

During bird necropsy, avian aspergillosis leaves telltale signs. The air sacs, unique to birds, often appear thickened and cloudy, with white, yellow, or green plaques of fungal growth. These lesions may extend to the lungs, which can show grayish-white nodules or areas of necrosis (dead tissue). In severe cases, the trachea and bronchi contain cheesy, caseous material—a mix of fungal debris and dead cells. If the infection has spread systemically, similar granulomas or abscesses may appear in the liver, spleen, or brain. These findings confirm the diagnosis and highlight the disease’s destructive impact.

Treatment: Managing and Preventing Avian Aspergillosis

Treating avian aspergillosis is challenging but possible with early intervention. Antifungal medications, such as itraconazole, voriconazole, or amphotericin B, are the cornerstone of therapy. These drugs can be administered orally, via nebulization (inhaled mist), or intravenously, depending on the bird’s condition and species. Supportive care—improved nutrition, hydration, and a stress-free environment—boosts recovery chances. In flocks, isolating sick birds and disinfecting the environment with antifungal agents like enilconazole helps curb spread.

Prevention is equally critical. Maintaining clean, dry, and well-ventilated housing reduces spore levels. Avoiding moldy feed or bedding, regularly cleaning water sources, and minimizing stress keep birds resilient. For high-risk settings like poultry farms or aviaries, routine health checks and air quality monitoring can catch problems early.

Conclusion: A Call to Action for Bird Health

Avian aspergillosis is a formidable foe, but with knowledge and vigilance, its impact can be minimized. From understanding its fungal origins to recognizing symptoms and pursuing treatment, bird caretakers play a vital role in safeguarding their flocks. Whether you’re a farmer, a pet owner, or a wildlife advocate, staying informed about this disease ensures healthier, happier birds. By prioritizing prevention and prompt care, we can reduce the toll of avian aspergillosis and protect these remarkable creatures for years to come.

Thanks so much for providing individuals with remarkably marvellous possiblity to read from this web site. It’s usually so ideal plus stuffed with a great time for me personally and my office colleagues to visit your blog really thrice in a week to learn the fresh guidance you will have. And indeed, I’m actually motivated with all the terrific advice you serve. Certain 3 tips on this page are indeed the most suitable we’ve had.