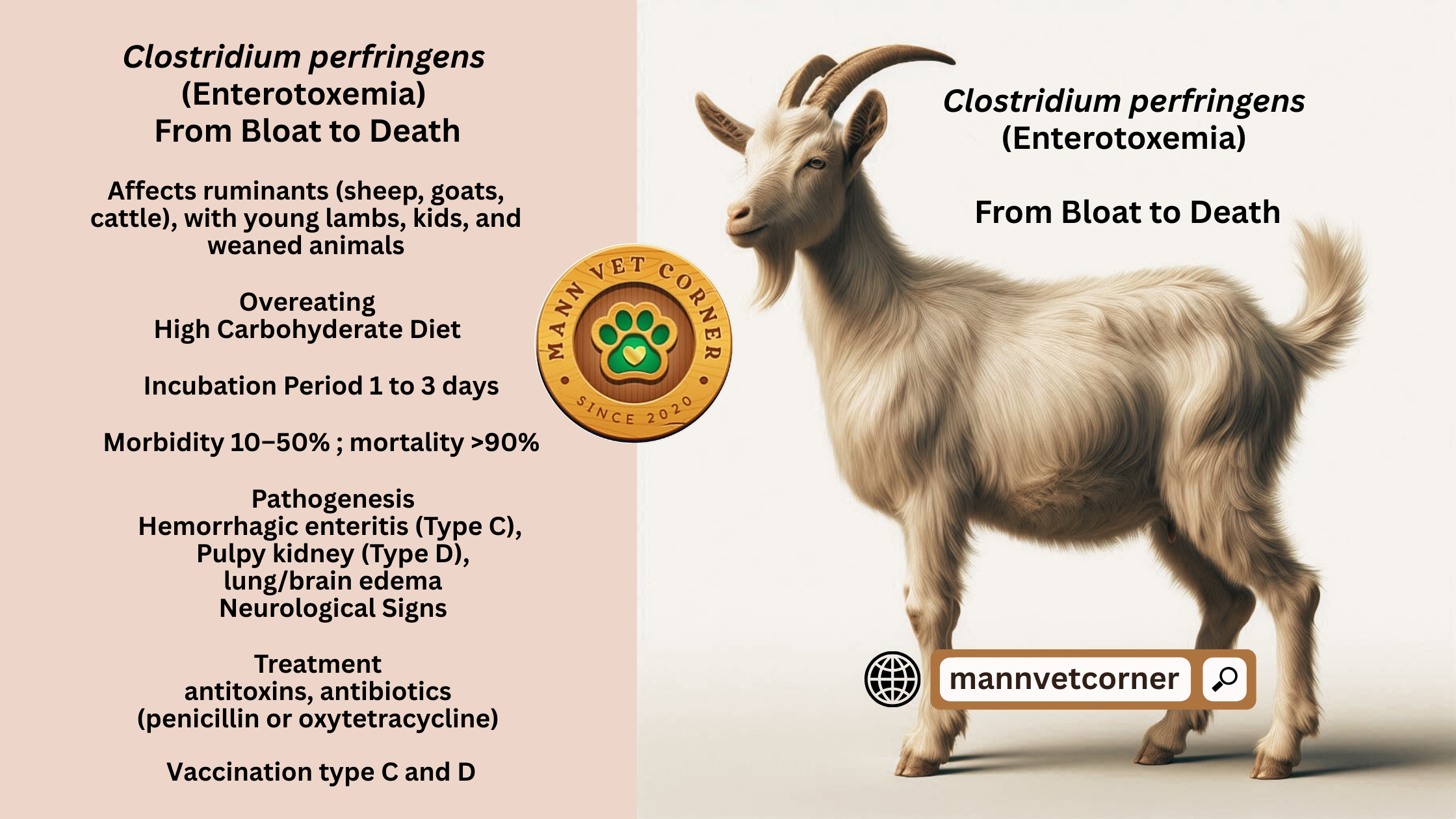

Enterotoxemia, often called “overeating disease,” is a serious bacterial condition that primarily affects ruminants like sheep, goats, and cattle. It’s caused by toxins produced by Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the environment and the gut of many animals. This blog dives nto the etiology, host susceptibility, incubation period, clinical signs, morbidity and mortality, pathogenesis, postmortem findings, and treatment of enterotoxemia, offering a clear and detailed guide for farmers, veterinarians, and animal health enthusiasts.

Etiology: The Root Cause of Enterotoxemia

Enterotoxemia is triggered by Clostridium perfringens, a gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium. This microbe is naturally present in soil, water, and the intestines of healthy animals. The disease occurs when Clostridium perfringens multiplies rapidly in the gut, producing potent toxins that damage tissues and disrupt bodily functions and develop enterotoxemia

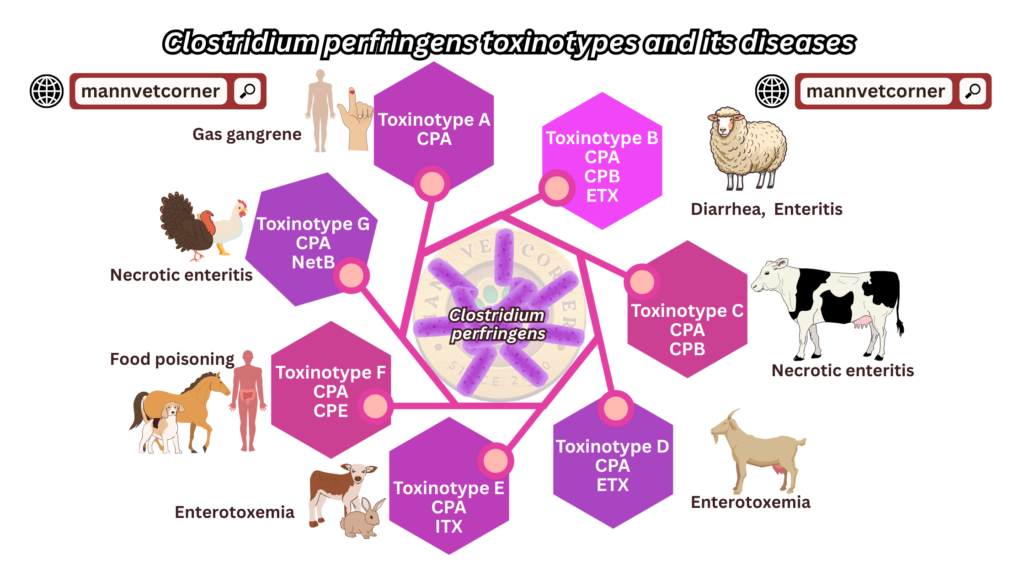

Clostridium perfringens is classified into five types (A, B, C, D, and E), each producing specific toxins. Types C and D are most commonly linked to enterotoxemia in ruminants:

- Type C produces alpha and beta toxins, causing severe intestinal damage, often in young animals.

- Type D produces alpha and epsilon toxins, leading to systemic effects, especially in older lambs and goats.

The disease is often sparked by dietary changes, like sudden access to rich feed, which disrupts the gut’s balance and allows C. perfringens to thrive.

| C. perfringens Type | Major Toxins | Susceptible Hosts | Clinical Signs | Associated Diseases |

| Type A | Alpha toxin | Cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, humans | Gas gangrene: Tissue necrosis, swelling, pain Enteritis: Mild diarrhea, abdominal pain | Gas gangrene Mild enteritis in animals Food poisoning in humans |

| Type B | Alpha, Beta, Epsilon toxins | Lambs, calves, foals | Sudden death Hemorrhagic enteritis: Bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain Neurological signs: Tremors, convulsions | Lamb dysentery (neonates) Hemorrhagic enterotoxemia in young ruminants |

| Type C | Alpha, Beta toxins | Neonatal lambs, goats, calves, piglets | Sudden death Severe hemorrhagic diarrhea Abdominal pain, weakness Occasional convulsions | Necrotic enteritis Struck (adult sheep) Enterotoxemia in neonates |

| Type D | Alpha, Epsilon toxins | Sheep, goats (especially lambs), cattle | Sudden death Neurological signs: Staggering, convulsions, head tilting Respiratory distress Mild diarrhea (less common) | Pulpy kidney disease Enterotoxemia in weaned lambs and goats |

| Type E | Alpha, Iota toxins | Cattle, rabbits (rare in sheep/goats) | Enteritis: Diarrhea, weight loss Intestinal necrosis (less severe) | Focal symmetrical encephalomalacia (rare) Enterotoxemia (uncommon) |

| Type F | Alpha, CPE (Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin) | Humans, Horse, occasionally dogs | Acute diarrhea, abdominal cramps Nausea, vomiting (in humans) Mild to severe gastroenteritis | Food poisoning in humans Non-foodborne gastroenteritis Diarrhea in dogs (rare) |

| Type G | Alpha, NetB toxin | Chickens (poultry) | Sudden death Diarrhea, depression Intestinal lesions, weight loss | Necrotic enteritis in poultry |

Host Susceptibility: Who’s at Risk?

Enterotoxemia primarily affects ruminants, with sheep and goats being the most susceptible. Cattle and camelids (like llamas and alpacas) can also be affected, though less frequently. The disease targets animals of all ages, but certain groups are more vulnerable:

- Young lambs and kids (under 6 weeks): Type C enterotoxemia is common in neonates due to their immature digestive systems and high milk intake.

- Weaned lambs and goats (2–6 months): Type D is prevalent in rapidly growing animals on high-grain diets.

- Adult animals: Less common, but sudden feed changes or stress can trigger outbreaks.

Factors increasing susceptibility include:

- Dietary shifts: Overfeeding on grain, lush pasture, or milk.

- Stress: Weaning, transportation, or overcrowding.

- Poor management: Inconsistent feeding or lack of vaccination.

Healthy, well-fed animals are paradoxically at higher risk, as rich diets fuel bacterial growth. Unvaccinated herds face greater danger.

Incubation Period: How Fast Does It Strike?

The incubation period for enterotoxemia is typically short, ranging from 12 hours to 3 days. The rapid onset is due to the fast proliferation of C. perfringens in the gut and the potent effects of its toxins. In acute cases, animals may die within hours of showing symptoms, making early detection challenging.

The incubation time varies based on:

- Toxin type: Epsilon toxin (Type D) acts faster than beta toxin (Type C).

- Diet: High-carbohydrate feeds shorten the incubation period.

- Animal health: Stressed or immunocompromised animals succumb quicker.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Spotting the Disease

Enterotoxemia presents a range of symptoms, depending on the C. perfringens type and the animal’s age. The disease often progresses rapidly, leaving little time for intervention. Common signs include:

Type C Enterotoxemia (Young Animals)

- Sudden death: Especially in neonates, with no prior symptoms.

- Abdominal pain: Kicking at the belly, arched back, or reluctance to move.

- Diarrhea: Bloody or dark, foul-smelling stools.

- Weakness: Lethargy, inability to stand, or collapse.

- Neurological signs: In severe cases, convulsions or head pressing.

Type D Enterotoxemia (Older Animals)

- Neurological symptoms: Staggering, head tilting, or convulsions (due to epsilon toxin affecting the brain).

- Sudden death: Common in feedlot lambs or goats on rich diets.

- Respiratory distress: Rapid, shallow breathing or gasping.

- Diarrhea: Less common than in Type C but may occur.

- Fever: Elevated body temperature in early stages.

Chronic cases are rare but may show weight loss, poor growth, or intermittent diarrhea. The nickname “overeating disease” reflects the link to dietary excess, especially in Type D.

Morbidity and Mortality: The Toll on Herds

Enterotoxemia can devastate livestock populations. Morbidity (the percentage of affected animals) varies widely, from 10% to 50% in unvaccinated herds during outbreaks. Mortality is high, often exceeding 90% in acute cases, as animals die within hours of symptom onset.

Key factors influencing morbidity and mortality:

- Vaccination status: Vaccinated herds have lower incidence and milder cases.

- Management practices: Overcrowding or poor feeding routines increase outbreaks.

- Animal age: Young and rapidly growing animals face higher mortality.

- Toxin type: Type D is often deadlier due to systemic effects.

In well-managed herds with vaccination programs, losses are minimal, but unvaccinated animals in high-risk conditions can suffer catastrophic losses.

Pathogenesis: How the Disease Unfolds

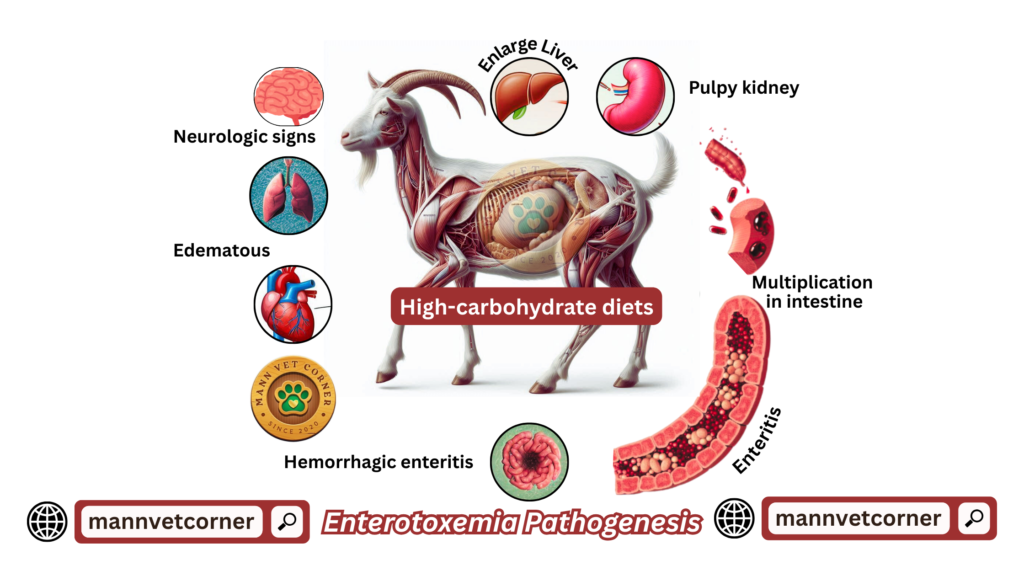

The pathogenesis of enterotoxemia begins with the rapid growth of C. perfringens in the gut, triggered by dietary or environmental factors. Here’s how it progresses:

- Bacterial Overgrowth: High-carbohydrate diets (grain, milk, or lush pasture) create ideal conditions for C. perfringens to multiply in the small intestine.

- Toxin Production:

- Type C: Beta toxin damages intestinal mucosa, causing necrosis, ulceration, and bloody diarrhea.

- Type D: Epsilon toxin is absorbed into the bloodstream, disrupting blood vessels and causing brain edema, leading to neurological signs.

- Systemic Effects: Toxins spread beyond the gut, damaging organs like the kidneys, liver, and brain. Epsilon toxin increases vascular permeability, causing fluid buildup and tissue damage.

- Rapid Decline: The combination of intestinal damage, toxin spread, and systemic shock leads to death within hours.

The speed and severity of pathogenesis make enterotoxemia a medical emergency in livestock.

Postmortem Findings: What the Autopsy Reveals

Postmortem examination is critical for confirming enterotoxemia, as clinical signs may be vague or absent. Key findings include:

- Intestinal Lesions:

- Type C: Severe hemorrhagic enteritis, with bloody, necrotic small intestines. The gut may appear dark red or black.

- Type D: Less severe intestinal damage but often shows congestion or mild ulceration.

- Fluid Accumulation: Edema in the lungs, brain, or abdominal cavity, especially in Type D cases.

- Kidney Changes: In Type D, “pulpy kidney” is a hallmark, where kidneys appear soft, swollen, and pale due to toxin damage.

- Liver and Spleen: Congestion or mild enlargement.

- Brain: Edema or softening in Type D cases, reflecting neurological damage.

Samples of intestinal contents, tissues, and blood can be tested for C. perfringens toxins to confirm the diagnosis. Rapid autolysis (tissue breakdown) post-death can complicate findings, so necropsies should be performed soon after death.

Treatment: Can Enterotoxemia Be Managed?

Treating enterotoxemia is challenging due to its rapid progression, but early intervention can save some animals. Strategies include:

Immediate Treatment

- Antitoxins: Administer C. perfringens Type C and D antitoxin to neutralize circulating toxins. This is most effective in early stages.

- Antibiotics: Penicillin or oxytetracycline can reduce bacterial growth, though they don’t address existing toxins.

- Supportive Care:

- Fluid therapy: To correct dehydration and shock.

- Pain relief: Anti-inflammatory drugs to ease discomfort.

- Dietary adjustment: Remove rich feeds and provide hay or low-energy diets.

Preventive Measures

- Vaccination: The cornerstone of control. Multivalent vaccines targeting C. perfringens Types C and D are highly effective. Vaccinate pregnant dams to pass immunity to offspring and young animals before weaning.

- Feed Management: Gradually introduce high-grain diets to prevent gut disruption. Avoid sudden feed changes.

- Herd Monitoring: Regular health checks and prompt isolation of sick animals.

Treatment success is limited in advanced cases, so prevention through vaccination and management is critical.

Conclusion: Staying Ahead of Enterotoxemia

Enterotoxemia is a deadly but preventable disease that demands proactive management. By understanding its causes, recognizing early signs, and implementing robust vaccination and feeding strategies, farmers can protect their herds from devastating losses. Regular veterinary consultation and good husbandry practices are key to keeping this “overeating disease” at bay.

I am constantly thought about this, regards for posting.