Introduction

A healthy cow udder is solid, uniformly shaped, and is a sophisticated organ vital for milk production, divided into four separate quarters, each containing its own teat and milk-generating system. In comparison, an udder affected by mastitis looks enlarged, warm, and sore, frequently producing clotted or off-colored milk. Bacteria enter the teat canal, causing inflammation and decreasing both milk quality and yield. Inadequate hygiene, injuries, or exposure to bacteria elevate the chances of mastitis, highlighting the importance of proper udder maintenance and consistent monitoring for dairy farm profitability. Farmers can avoid mastitis by implementing hygienic milking practices, disinfecting teats after milking, and conducting regular health assessments to maintain a high-yield, disease-free herd. In this article first of all, discuss its normal anatomical structure, and then overview the mastitis udder.

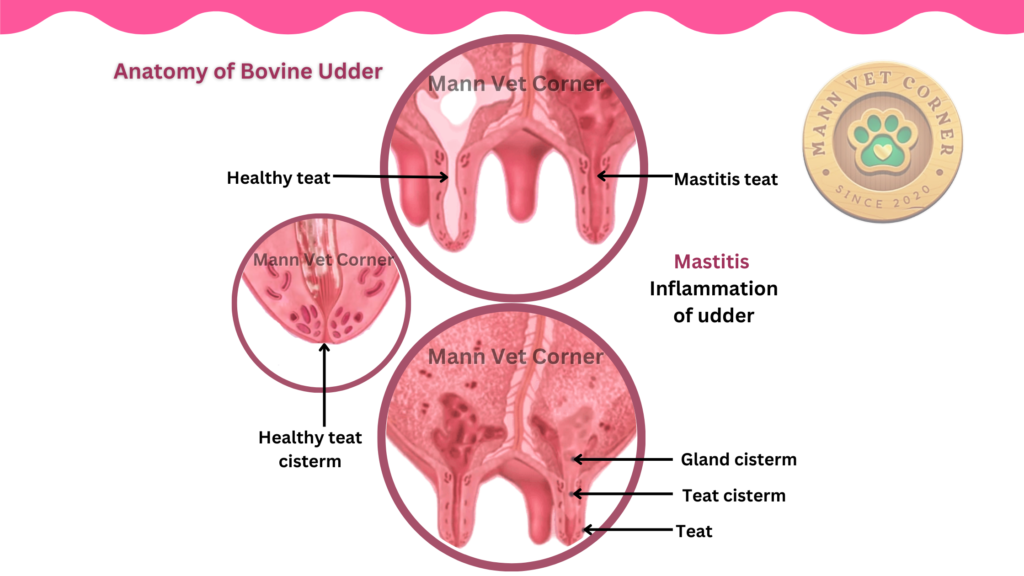

Anatomical Structure of Cow Udder:

Quarters and Teats: Each of the four teats functions separately, limiting the transmission of infections among them. Milk is released through the teat canal while milking.

Alveoli: These clusters resembling grapes generate milk, aided by secretory cells. Milk production takes place in this location, fueled by nutrients from the blood.

Duct System: Milk flows from the alveoli through a series of ducts to the gland cistern (a storage compartment in each quarter) and subsequently to the teat cistern before leaving through the teat canal.

Assistance and Security of Cow Udder:

Suspensory Ligaments: Made of connective tissue, these ligaments secure the udder to the body wall, avoiding sagging and potential injury. Weaknesses may result in udder failure, especially in cows with high production.

Physiological Systems of Cow Udder:

Blood Supply: Provides essential oxygen and nutrients needed for milk production. High-yielding cows need strong circulation to sustain ongoing milk production.

Lymphatic System: Removes surplus fluids and fights off pathogens, crucial for preventing infections such as mastitis.

Hormonal Control of Cow Udder:

Prolactin: Triggers milk production after giving birth.

Oxytocin: Activates the milk let-down reflex by contracting alveolar muscles, propelling milk into the ducts. Effective milking practices (e.g., regular timing, minimizing stress) enhance hormone secretion.

Mastitis: Warning Signs

Inflammation of the mammary gland is called mastitis, primarily caused by microbial infections. it affecting milk production, quality, and cattle welfare.

Mastitis is generally divided into clinical and subclinical forms, each with different characteristics, causes, and management approaches.

1. Clinical Mastitis

Clinical mastitis is characterized by visible signs of udder inflammation and alterations in the appearance of milk. It varies from mild to severe and may involve systemic symptoms.

Causes:

- Bacterial Pathogens:

- Infectious: transmitted during milking (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae).

- Environmental: Originate from the cow’s surroundings (e.g., E. coli, Streptococcus uberis, Klebsiella spp.).

- Coliforms (e.g., E. coli, Klebsiella) commonly cause acute and severe mastitis.

- additional Pathogens: Fungi, algae, or physical trauma may also cause the clinical mastitis

Symptoms:

- Localized Signs:

- Swollen, warm, or painful udder condition.

- Abnormal milk (clots, particles, watery, or discolored).

- Systemic Signs (in severe cases):

- symptoms include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, dehydration, or shock (e.g., in toxic coliform mastitis).

Categorization by Severity:

- Mild: Milk abnormalities (e.g., flakes) without swelling of the udder.

- Moderate: Milk alterations + udder inflammation (swelling, redness).

- Severe: Systemic disease (fever, shock) with alterations in udder and milk.

How to identify:

- Visual Examination: Alteration in the Udder and milk.

- California Mastitis Test (CMT): identifies elevated somatic cell count (SCC).

- Bacterial Culture/PCR: detect the causative pathogens.

- Milk pH Testing: Contaminated milk has higher pH (>6.8).

How to treat:

- Antibiotics: Broad-spectrum (such as cephalosporins) or pathogen-specific infusions for intramammary teats.

- Anti-inflammatory medications: NSAIDs (such as flunixin) to reduce pain and swelling.

- Fluid Treatment: For cows that are dehydrated or septicemic conditions.

- Milk Discard: Increase the withdrawal times to prevent antibiotic residues.

2. Subclinical Mastitis

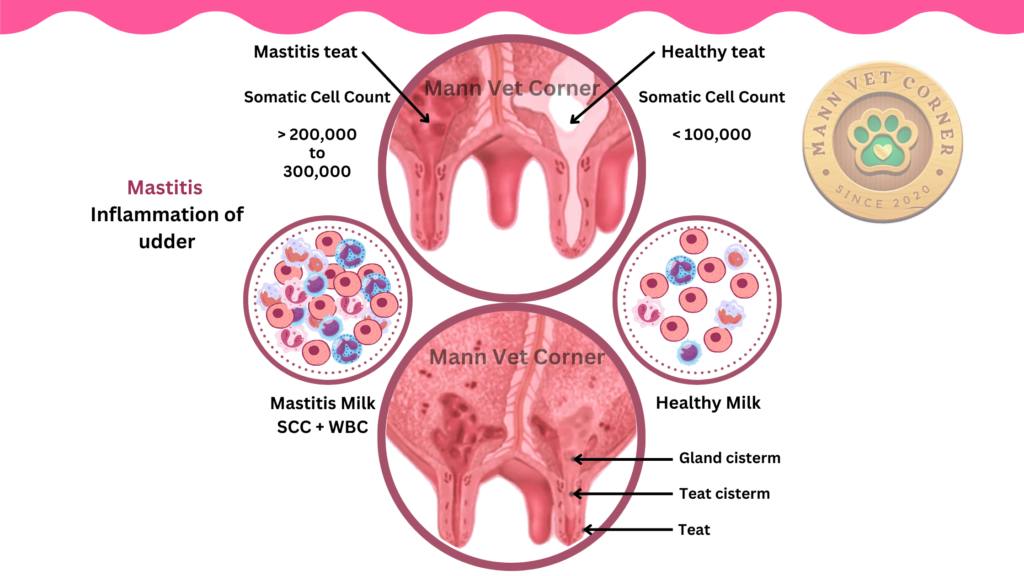

It does not show noticeable signs but leads to increased the somatic cell counts (SCC) and lower milk quality. Subclinical mastitis is more common than clinical mastitis and frequently occurs before the clinical cases.

Causes:

- Main Pathogens:

- Staphylococcus aureus (most prevalent, prolong infections).

- Streptococcus agalactiae (infectious, transmitted during milking).

- Environmental streptococci (e.g., Streptococcus uberis).

- Risk Factors: quality of milking un-hygienic, insufficient teat disinfection, and stress or pressure of milking.

Symptoms:

- No apparent signs of inflammation of udder or milk alteration.

- Hidden Effects:

- decrease milk production (10–30% per cow).

- Increased SCC (>200,000 cells/mL in bulk tank milk).

- Decreased milk quality (lower lactose, casein (milk protein), and butterfat levels).

How to identify:

- Somatic Cell Count (SCC): Very Common and Trademark for identification of subclinical mastitis.

- A SSC level of Individual cow >200,000 cells/mL indicates an infection.

- California Mastitis Test (CMT): On-farm test with semi-quantitative results.

- Bacterial Culture: For ongoing infections detection (e.g., Staph. aureus).

- Electrical Conductivity Tests: Increased conductivity in infected milk.

Impact:

- Financial Losses:

- Decreased productivity and penalities on the milk quality from processors.

- Increased chances of clinical flare-ups.

- Herd Health: Serves as a source for infectious pathogens.

How to manage:

- Culling: Long-term carriers (e.g., Staph. aureus-positive cows).

- Dry Cow Treatment: Antibiotics or teat administratered during the dry phase.

- Enhanced Milking Procedures: Disinfection of teats before- and after-milking.

- Nutrition: Give vitamins (A, E) and minerals (selenium, zinc) to strengthen immunity.

Key Differences Between Clinical and Subclinical Mastitis

| Parameter | Clinical Mastitis | Subclinical Mastitis |

| Visibility | Visible signs (udder/milk) | No visible symptoms |

| Identification | Visual inspection, CMT, culture | SCC, CMT, culture |

| Pathogens | E. coli, Klebsiella, Strep. uberis | Staph. aureus, Strep. agalactiae |

| Economic Impact | Acute losses (milk discard) | Chronic losses (yield/quality) |

| Prevalence | 5–10% of cases | 90–95% of cases |

Bovine Mastitis: General Considerations

- Contagious vs. Environmental:

- Contagious: Spread cow-to-cow during milking (e.g., Staph. aureus).

- Environmental: Pathogens thrive in wet bedding or soil (e.g., E. coli).

- Chronicity: Subclinical infections often become chronic, leading to recurrent clinical cases.

- Zoonotic Risk: Rare, but raw milk from infected cows may transmit pathogens (e.g., Staph. aureus).

Prevention strategies of mastitis

- Milking Precautions:

- Wear gloves, sanitize teats before/after-milking, and keep milking equipment in good condition.

- Environmental:

- Ensure clean and dry bedding; minimize mud and manure in living areas of cows.

- Vaccination:

- E. coli J5 vaccines can decrease severity; Staph. aureus vaccines under development.

- Monitoring:

- Constant SCC testing, culturing high-SCC cows, and monitoring mastitis incidence.

Conclusion

Bovine mastitis, whether clinical or subclinical mastitis, requires proactive management to protect herd productivity and maintain milk quality. Clinical cases demand immediate treatment, wherease subclinical infections require long-term observation and prevention measures. Integrating hygiene, vaccination, and data-driven approaches (e.g., SCC monitoring) reduces losses and improves dairy sustainability. Tackling both forms systematically is key to minimizing antibiotic usage and their resistance.