Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia (CCPP) is one of those diseases that makes every small ruminant vet’s shoulders tense up just a little. This devastating disease, commonly called CCPP in small ruminants, is highly infectious and often severe—if left unchecked, it can rip through herds with alarming speed. I’ve seen cases where small ruminant farmers lose a significant portion of their flock to CCPP before they even realize what’s happening. The tricky thing about CCPP in goats and other small ruminants is that it can look like other respiratory infections at first glance. But once it takes hold, the damage it does to the lungs is unmistakable. Today, we’ll break down everything you need to know about CCPP in small ruminants—from the causes of CCPP to how to treat CCPP in small ruminants (and, more importantly, how to prevent CCPP in small ruminants).

Etiology: What Causes CCPP?

CCPP is caused by Mycoplasma capricolum subspecies capripneumoniae (Mccp). Mycoplasmas are… well, they’re odd. They lack a cell wall, which makes them resistant to many common antibiotics (more on that later). They’re also notoriously fastidious, meaning they’re picky about growth conditions in the lab.

This particular mycoplasma is host-specific—mostly affecting goats, though sheep can occasionally get infected (usually with milder symptoms). The bacteria spreads through respiratory droplets, so close contact is the main transmission route. Think shared water troughs, crowded pens, or even just nose-to-nose greetings between animals.

One thing worth noting: CCPP isn’t zoonotic. So, while it’s devastating for goats, humans don’t have to worry about catching it.

Host Susceptibility: Who’s at Risk?

Goats are the primary victims here, especially:

- Younger goats (they tend to have more severe cases)

- Stressed or immunocompromised animals (poor nutrition, concurrent infections, etc.)

- Herds with no prior exposure (naïve populations get hit hardest)

Sheep can carry the bacteria, but they usually don’t show severe symptoms. That said, they might act as silent spreaders, which complicates control measures.

I’ve noticed that certain breeds seem more susceptible, but the data isn’t entirely clear-cut. What is clear is that overcrowding and poor ventilation turn a bad situation into a disaster.

Incubation Period: How Fast Does It Spread?

The incubation period ranges from 6 to 21 days, which is both a blessing and a curse. A blessing because it gives you a small window to intervene before things escalate. A curse because by the time clinical signs appear, the disease has likely already spread.

In some outbreaks, I’ve seen goats develop symptoms within a week. Others take longer. The variability makes it hard to predict, so early detection is key.

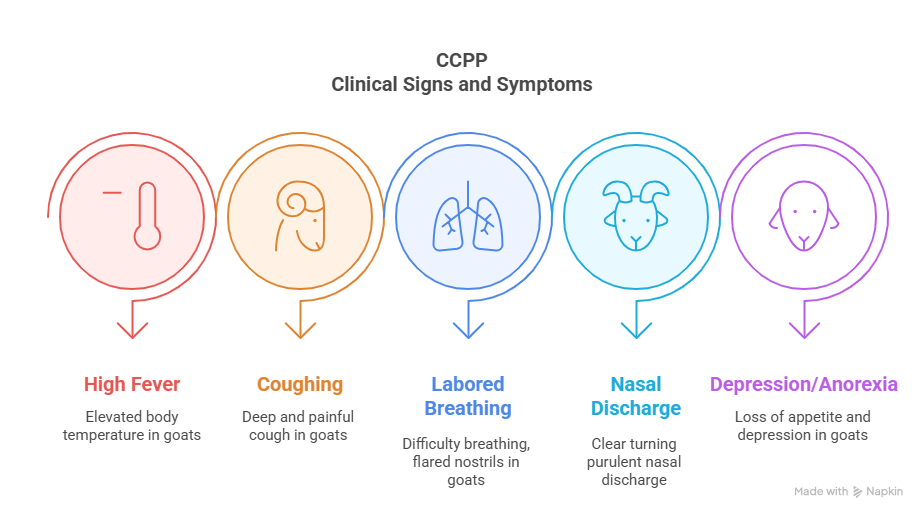

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: What to Look For

CCPP doesn’t mess around. The most common signs include:

- High fever (up to 41°C or 106°F)

- Coughing (often deep and painful)

- Labored breathing (you might notice extended necks and flared nostrils)

- Nasal discharge (usually clear at first, then turns purulent)

- Depression and anorexia (they just stand there, head down, not interested in food)

In severe cases, you’ll see:

- Pleuropneumonia (fluid buildup in the chest, leading to a “thumping” sound on percussion)

- Recumbency (they go down and can’t get back up)

One thing that always sticks with me: the way affected goats grunt when they breathe. It’s a soft, painful sound—definitely not something you forget.

Morbidity and Mortality: How Bad Can It Get?

Morbidity (infection rate) can reach 80-100% in susceptible herds. Mortality (death rate) varies, but without treatment, it’s often 60-80%.

The worst outbreaks I’ve seen were in herds with no prior vaccination. Kids and weak adults usually go first. Even with treatment, survivors may have chronic lung damage, reducing their productivity.

Pathogenesis of CCPP: A Deep Dive into Disease Development

Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia (CCPP) doesn’t just infect goats—it dismantles their respiratory system in a systematic, almost ruthless way. Understanding the step-by-step progression isn’t just academic; it helps vets predict clinical signs, refine treatment, and explain to farmers why early intervention is so critical.

Let’s break it down—stage by stage.

1. Entry and Colonization: The Bacteria Settles In

The journey begins when an infected goat coughs, releasing aerosolized Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capripneumoniae (Mccp) into the air. Another goat inhales these droplets, and the bacteria latch onto the ciliated epithelial cells lining the lower respiratory tract—primarily the bronchi and alveoli.

Why the lungs?

- Mycoplasmas lack a cell wall, making them fragile in harsh environments. The moist, warm airways are perfect for them.

- They have specialized adhesion proteins that bind tightly to respiratory cells, avoiding expulsion by mucus or ciliary action.

At this point, the goat isn’t showing symptoms yet. But the bacteria are already replicating, quietly setting up shop.

2. Immune Evasion: The Silent Invasion

Mycoplasmas are masters of stealth. Unlike many bacteria, they don’t trigger an immediate, aggressive immune response. Here’s how they fly under the radar:

- No cell wall = No endotoxins. Most bacteria set off alarms via molecules like LPS (lipopolysaccharide), but mycoplasmas don’t have these.

- Antigenic mimicry. Their surface proteins resemble host molecules, delaying immune recognition.

- Biofilm formation. Some strains produce biofilms, shielding themselves from antibodies and phagocytes.

This stealth phase explains the 6–21 day incubation period. The goat seems fine, but the bacteria are multiplying unchecked.

3. Inflammation and Tissue Damage: The Battle Begins

Once the bacterial load reaches a critical threshold, the immune system finally reacts—violently.

Key Players in the Destruction:

- Macrophages and neutrophils rush in, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6).

- Reactive oxygen species (free radicals) damage both bacteria and lung tissue.

- Fibrin deposits form as the body tries to wall off the infection, leading to pleurisy (inflammation of the pleural membranes).

What the Goat Feels:

- Fever (from cytokines flooding the bloodstream).

- Painful breathing (pleurisy makes every breath feel like a knife stab).

- Coughing (the lungs are filling with debris and fluid).

4. Lung Consolidation: The Point of No Return

If the infection isn’t controlled, the lungs undergo hepatization—a term borrowed from pathology that means “liver-like” transformation. Here’s what happens:

- Alveoli fill with exudate (fluid, fibrin, dead cells).

- Lobes become firm and airless—normally spongy lung tissue turns solid.

- Gas exchange plummets, leading to hypoxia (oxygen deprivation).

Clinically, this looks like:

- Severe dyspnea (open-mouth breathing, extended neck).

- Crackles and pleural friction rubs on auscultation.

- Dull percussion sounds over affected lobes.

At this stage, even with treatment, some lung damage may be permanent.

5. Systemic Complications: Beyond the Lungs

The chaos isn’t confined to the chest. As inflammation escalates:

- Bacteremia (bacteria enter the bloodstream).

- Endotoxemia (even without classic endotoxins, mycoplasmas release harmful metabolites).

- Multi-organ failure (kidneys and liver suffer from hypoxia and toxin overload).

Terminal Signs:

- Recumbency (too weak to stand).

- Cold extremities (circulatory collapse).

- Death (often from suffocation or septic shock).

Why Some Goats Die While Others Recover

Not all cases are equally severe. Factors that tilt the balance:

| Survival Favors: | Death Favors: |

|---|---|

| Early antibiotic treatment | Delayed intervention |

| Strong immune status (good nutrition) | Concurrent infections (e.g., PPR, parasites) |

| Low-stress environment | Overcrowding, poor ventilation |

Postmortem Findings: What You’ll See on Necropsy

If you’ve ever done a necropsy on a CCPP case, you know the lesions are pretty distinctive:

- Fibrinous pleurisy: The pleural surfaces are covered in a yellowish, sticky exudate.

- Lung consolidation: The ventral lobes are firm, dark red, and don’t collapse when the chest is opened.

- Pleural effusion: Often several liters of straw-colored fluid in the chest cavity.

It’s one of those cases where the diagnosis is often obvious just from the gross pathology.

Treatment: Can We Save Them?

Yes, but timing is everything. Here’s what works:

1. Antibiotics

- Tylosin (10 mg/kg IM, once daily for 5-7 days)

- Oxytetracycline (20 mg/kg IM, every 72 hours)

- Florfenicol (20 mg/kg IM, every 48 hours)

Note: Beta-lactams (like penicillin) won’t work—remember, mycoplasmas lack a cell wall.

2. Supportive Care

- Anti-inflammatories (flunixin meglumine helps with pain and fever)

- Fluid therapy (dehydration worsens everything)

- Isolation (to prevent further spread)

3. Vaccination (Prevention is Always Better)

- Live attenuated vaccines are available in some countries.

- Killed vaccines exist but are less effective.

If you’re dealing with an outbreak, vaccinate the healthy ones first. The sick ones may not respond well.

Final Thoughts

CCPP is brutal, but it’s not unbeatable. Early detection, proper antibiotics, and good herd management can make all the difference.

If you’re in an endemic area, vaccination should be non-negotiable. And if you see a goat with a high fever and that telltale grunt? Act fast. The sooner you intervene, the better the outcome.

Have you dealt with CCPP in your practice? What strategies worked for you? Drop a comment—I’d love to hear your experiences.